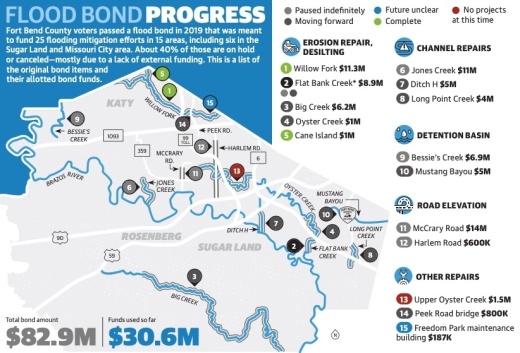

Flooding was still front of mind for many Fort Bend County residents when voters approved the county’s $83 million flood bond in November 2019—two years after Harvey devastated the area in August 2017.

Mark Vogler, the Fort Bend County Drainage District general manager and chief engineer, said most of the paused projects are due to a lack of supplemental funding. He described the county’s bids for grants to use with bond money as “wishful thinking.”

“These projects were just so, so massive in cost that the county was saying, ‘We don’t have the funds right now to do this bigger project—but let’s see if we can get a grant, and if we can get a grant, maybe we can move the project forward by percentage of it,’” Vogler said.

Despite the delays, some of the bond work is being done in Missouri City through cooperation with city officials. Meanwhile, both Missouri City and Sugar Land officials said they are working on their own drainage mitigation projects.

Funding limbo

If the county had been able to secure the external funding to match its $83 million in bond funding, it would have translated to more than $250 million in drainage projects. At this point, however, less than half of the bond funds are being used, Vogler said.

One stalled project affecting the Sugar Land and Missouri City area is a $6.25 million flooding mitigation structure at Flat Bank Creek, which was delayed due to lack of funding. That structure would have aimed to prevent flood waters from backing up.

While Flat Bank Creek’s flood structure project is stalled, its $2.5 million erosion repair project secured the funding it needed and is moving forward with the bid process. Fort Bend County Drainage District officials said they are working with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to repair erosion damage and sloughing.

“The banks are starting to slough, which means they’re starting to slide off and just fall in,” Vogler said. “If the bank falls in, the levee at the top is going to have a tendency to fall in or lose stability.”

Additionally, Vogler said the county applied for $96 million in funding from the Texas General Land Office in 2020 but learned in May it did not receive any. Moreover, while the bond funds are available now, the funds have an expiration date in 2044.

“The bond funds are only good for 25 years,” Vogler said. “If 26 years from now something happens to Oyster Creek, am I still going to be able to get the $1.5 million? I don’t know.”

Moreover, the channel repair, erosion repair and desilting projects were meant to restore the damage done by Hurricane Harvey—not mitigate future damage, Vogler said.

“It’s not going to be any better, and it’s not gonna be any worse,” Vogler said. “It’s going to be the same. So, the bond money was to put things—in most cases except for evacuation routes—to put things back like they were [before Hurricane Harvey].”

While many projects were not able to secure the funding needed to move forward, others were fully funded by the bond or secured funding elsewhere, such as FEMA or the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

The Ditch H project in the Sugar Land area, as well as the Mustang Bayou and Long Point Creek projects near Missouri City, were funded entirely by the bond—and the county secured external funding to move the Oyster Creek project forward.

“We’re always going to continue to monitor,” Vogler said. “Any time there’s grant money out there that’s available, we’d be interested in it.”

City efforts

While the county continues to work toward securing funding for additional projects, both Missouri City and Sugar Land are working independently to improve their preparation for another major flooding event.

Sugar Land’s City Engineer Jessie Li said the city has a long history of investing in drainage improvements.

“We have done a lot,” she said. “The city actually spent more than $50 million in drainage improvements in the past eight to 10 years.”

Sugar Land has a $6 million project under construction in the Settlers Way area. It should reduce street ponding and home flooding by adding another storm sewer outfall and replacing the existing storm sewer inlets and pipes. Officials said they expect the project to reach completion in September.

Additionally, Li said the city has a project in the Chimneystone area under design, which is estimated to cost $16.5 million. It will be funded from the city’s general obligation bond passed in 2020.

Shashi Kumar, Missouri City’s director of public works and city engineer, said the city implemented a new flood alert system in July, which was funded in part through a grant from the GLO. The $300,000 system consists of devices that measure rainfall and provide real-time stream-level information.

“[Missouri City City Council] takes drainage seriously,” Kumar said. “This area is flood prone. We’re flat. We have a number of rain challenges.”

Kumar said the city is working on designing drainage improvements for the Cangelosi Ditch widening project. It will cost $2 million with nearly half of the funds coming from GLO funding. Construction is projected to begin next year, Missouri City officials said.

Missouri City is also moving forward independently with Willow Waterhole detention improvements. That project is under design with construction estimated to begin in 2022. It aims to expand detention capacity to accommodate watershed growth. It will cost $2.1 million—funded by the city’s capital improvement program. Additionally, the city is working with the Fort Bend County Drainage District to execute the drainage improvements at Long Point Creek—which are funded through the 2019 bond.

That project aims to improve the channel and create additional easements, officials said.

“[We are] not just sitting, but we’re trying to do proactively more projects,” Kumar said.

Risk Rating 2.0

While city and county officials are working to make improvements to mitigate flooding, Texas residents who insure their properties through the National Flood Insurance Program will soon be subject to a cost increase.

FEMA said in April it will be implementing a new methodology to determine a property’s flood risk. Dubbed Risk Rating 2.0, the change will go into effect Oct. 1, increasing flood insurance rates for 77% of NFIP policyholders, FEMA estimated.

In Fort Bend County, more than 95% of the 64,584 NFIP policyholders will see a price increase, Sugar Land officials said in a news release.

Risk Rating 2.0 will go into effect Oct. 1 for new flood insurance policyholders and April 1, 2022, for renewed policies. While prices are expected to increase, it is federally mandated that a flood insurance premium cannot go up by more than 18% per year, FEMA said.

Additionally, flood insurance policies take 30 days to go into effect, so any policy bought after Sept. 1 will not qualify for being grandfathered in. Both Sugar Land and Missouri City have publicly voiced their opposition to the change.

“The new methodology will fundamentally change the way insurance premiums are calculated and may include making flood insurance mandatory for properties protected by levees—even if they are accredited,” Li said in an email.