FBISD officials felt the most respectful option was to rebury the remains sooner rather than later, despite pushback from community members who felt the Sugar Land 95 should remain exhumed until DNA analysis is completed and descendants are identified.

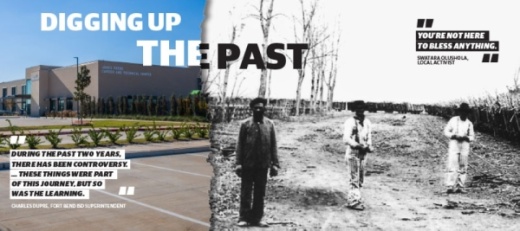

“You’re not here to bless anything,” Swatara Olushola, a resident who has provided input throughout the reburial process, protested at the Nov. 17 ground blessing ceremony at the James Reese Career and Technical Center. “How are you going to bless the ground you desecrated?”

Conducting DNA research

According to the district, DNA analysis could take up to four years to complete.

“Due to the nature of this work with ancient DNA, it is anticipated that [analysis] could take several years, which is why the district decided it would be more respectful to move forward with the reburial now,” said Amanda Bubela, FBISD’s director of external communications and media relations.

The Sugar Land 95 are believed to be African American men who provided labor through Texas’ convict labor leasing program—essentially slavery that was practiced in the late 1800s and early 1900s after slavery was abolished.

In June, the district was authorized by the Texas Historical Commission to extract bone and tooth samples from the bodies for DNA testing. The samples were then sent to the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, affiliated with The University of Texas at Austin, to act as the storehouse.

Although the TARL is storing the remains, the lab is not conducting the research, TARL Head of Collections Marybeth Tomka said in an email.

“TARL is not doing the research on the samples from the Sugar Land site,” Tomka said. “We are merely the repository for the collected samples and the results when they ultimately come in.”

Earlier this past fall, the Texas Historical Commission also approved a research proposal for the extraction and analysis of the DNA at the University of Connecticut, Bubela said.

“Researchers have secured funding for the first batch of DNA extractions,” Bubela said. “Additional funding will be needed to fund the remaining DNA extractions, analysis, comparisons to existing databases, public outreach and genealogical studies.”

The University of Connecticut needs $40,000-$80,000 to complete the total project and has secured about $3,000, according to Deborah Bolnick, an associate professor at the university.

From discovery to reburial

FBISD purchased the land for the James Reese Career and Technical Center in 2011. Before buying the land, the district commissioned an investigation of the site that revealed the property was formerly part of a 2,000-acre tract of Central State Prison Farm land, according to district officials.

With this information, the consulting firm that administered the investigation told the district no additional archeological work would be necessary, FBISD officials said.

Local activist Reginald Moore warned the district they might find historic human remains ahead of the discovery in February 2018.

The Sugar Land 95 were exhumed from June 2018 until November 2019.

In September, the board of trustees approved a $284,000 contract with Missouri City Funeral Directors at Glen Park for reburial services.

“I assure you, we are working with an honorable and capable professional who respects the sheer weight of the responsibility given to them,” FBISD Superintendent Charles Dupre said during the Nov. 17 ceremony.

As of mid-December, the portion of the school where the human remains were reburied was enclosed by a fence lined with black tarps.

A formal memorial will be held in the spring, and FBISD students will help lead the program commemorating the discovery, Dupre said.

“During the past two years, there has been controversy, heated conversation; decisions made and then revisited,” Dupre said. “These things were part of this journey, but so was the learning; so was the engagement, the partnerships, the opportunity to shed light on the past.”