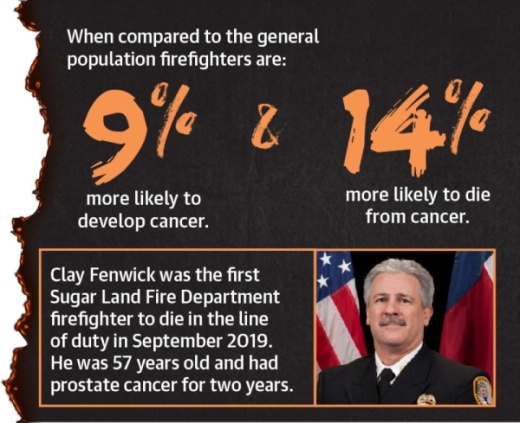

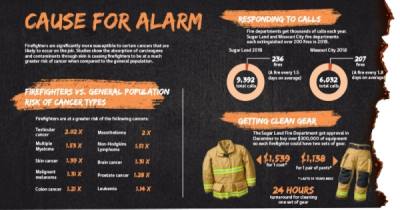

Overall, firefighters are 9% more likely to develop cancer and 14% more likely to die from cancer than the general population. However, firefighters are at a 114% to 202% greater risk of developing certain cancers, such as mesothelioma, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, malignant melanoma and leukemia as these are classified as common occupational illnesses, said Doug Boeker, Sugar Land Fire-EMS chief.

“We have a number of retirees that have had cancer, and we’ve had a number of current employees that have had some sort of cancer,” Boeker said. “The number of skin cancers on chests, necks and faces ... is very similar to the absorption areas that studies show are highest.”

Both Sugar Land and Missouri City fire departments have taken steps in the last few years to attempt to diminish these risks, such as purchasing new gear and emphasizing health and wellness.

Assessing the risks

In Sugar Land, Assistant Fire-EMS Chief Clay Fenwick died in September at the age of 57 after battling prostate cancer for nearly two years. He served 28 years in the Sugar Land Fire Department and was the first firefighter in the history of the department to die while he was still employed from cancer he developed on the job, Boeker said.

“It’s a dangerous business both in the fire and afterwards,” said Steve Porter, Sugar Land District 1 City Council member. “We want to do everything we can do to continue to minimize that exposure.”

The International Association of Fire Fighters started recognizing cancer-related firefighter line-of-duty deaths in the early 1980s, IAFF Press Secretary Tim Burn said. However, at a local level, this has only been considered a mainstream problem in the last few years, said Tommie Holliday, president of the Sugar Land Professional Firefighters Association.

Monitoring cancers has become more common in the last decade, Missouri City Fire Chief Eugene Campbell said. Agencies like the U.S. Fire Administration have put forth initiatives promoting health and wellness to combat and prevent cancer as much as possible, Campbell said.

“I would say over the last 10 years [it’s been more top of mind],” Campbell said. “The firefighter joint initiative goes back to the mid-2000s, but I think it’s been growing since, especially with the way the country has changed and focused more on health and wellness.”

In Missouri City, Campbell said a priority is keeping firefighters in shape through physical fitness and eating right.

“From our perspective, we make sure that we tell recruits when they get into school, this year we have a new module that’s not only focused on health and wellness, but their personal accountability to make sure that they start [their career] right and they finish right,” Campbell said.

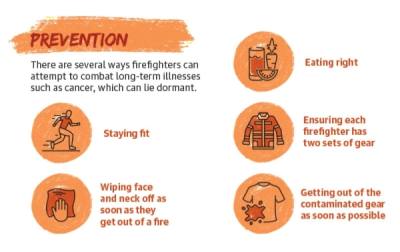

An important measure that limits the amount of time firefighters are exposed to carcinogens is ensuring each firefighter has two full sets of protective equipment.

Campbell said Missouri City already has this in place. Boeker went before Sugar Land City Council in December asking for approval of more than $300,000 worth of new pants and coats for staff to have two sets each.

A misconception formed about firefighters was that inhaling smoke was what made them more susceptible to cancer, Boeker said. However, since the ‘80s firefighters have been required to wear self-contained breathing apparatuses that supply clean, compressed air for 30-45 minutes at a time, he said.

“Now, the latest thought is that we’re actually absorbing the products of combustion through our skin,” he said. “The gear that they wear has an outside abrasive layer that protects them from physical injury. But then there’s a vapor barrier in there, and it’s kind of like a plastic lining that keeps steam from coming through. It turns out that the particles that we’re talking about are so small that they go through that, and it gets on the firefighters’ skin.”

One issue with gear is that once they are contaminated the first time, they are never 100% clean again, Boeker said. Gear should last about 10 years, but with the wear and tear they see, it’s abnormal for them to last that long.

After a fire, firefighters are contaminated, Boeker said. High absorption rates have been found in the neck, armpits and groin areas, and this absorption can continue for several hours.

“It’s a real problem for us, and we want to get them in clean gear,” Boeker said. “But that’s just one of the things that we’re doing. What we find is that it doesn’t matter how much gear you buy, if our practices don’t change, we don’t think we can keep them healthy.”

Combating cancer

Holliday said one reason why it can be hard to get a full picture of this epidemic is that firefighters are not self-reporting health issues ranging from mental health concerns to cancer.

“It’s very difficult for us to talk about when we’re weak or admit when we can’t or we don’t know how to fix it or that kind of thing,” Holliday said. “And I think that part of the fire service is hindering us from being able to get good, solid research. It’s probably a whole lot worse than what we even realize. But we just haven’t got all of the data because we’re so resistant to giving it up.”

Boeker said a priority is getting firefighters screened more often for cancers and getting more physicals. The department provides physicals every year to the firefighters, but that does not necessarily catch developing cancers.

“That’s kind of an emerging market in the medical industry is firefighter physicals,” Boeker said. “We’re trying to expand our physicals in a logical way that will give us the earliest detection of a problem.”

Boeker said the challenge right now is determining what the best practices are for physicals and cancer screenings.

“There’s not a one stop shop that will get it all,” Boeker said. “The only way to get it all would be like you’re doing a complete body ultrasound. You’re doing an MRI of the head to check for brain cancer. You’re doing a colonoscopy every year for firefighters. And I mean, obviously, these are cost prohibitive. You’d be into the tens of thousands of dollars per firefighter.”

Holliday said he has spoken with several different departments that have screened their firefighters and found cancer in one or two employees. It was caught early enough that it ends up saving money that would be spent on someone who develops more aggressive cancer on the job that is discovered later on, Holliday said.

“We are working with the department; we’re involved in a lot of these conversations,” Holliday said. “We are feeding them information, and I think everybody’s on the same page. Cancer is bad, we’ve got to stop it, we’ve got to stop the bleeding that’s occurring in the fire service. I think we’re reacting well, but probably not reacting fully just yet.”

The IAFF advocates for post-retirement insurance coverage, Burn said.

“Most of the laws that presume certain cancers are occupational have provisions to cover fire fighters for a period of time post-retirement,” Burn said. “The amount of time covered varies by state.”

However, under Texas law, once a firefighter “separates employment” or retires, he or she is no longer insured, and any expenses from cancers that would have been developed on the job are no longer covered, Holliday said.

“What I tell our guys is anytime you even think about getting close to retirement go get every kind of test imaginable done, even if you have to pay out of your own pocket,” Holliday said. “Make as sure as you possibly can that you don’t have anything before you do retire because you lose these benefits.”