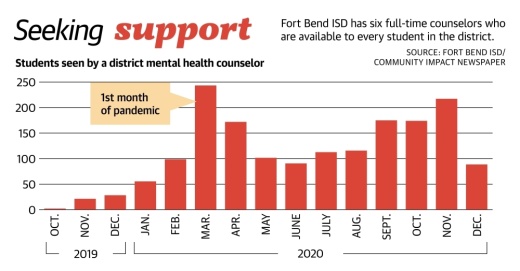

The number of FBISD students seen by a district mental health counselor jumped from 99 in February 2020 to 243 in March 2020. As the demand for care increased and the program continued to ramp up, the number of students seen during the remainder of 2020 was consistently higher than prepandemic numbers.

The district’s initial plan for mental health services would have embedded mental health centers on eight campuses. However, Priti Avantsa, FBISD’s coordinator for mental health and social work services, said FBISD’s plans changed in January 2020. Now, instead of the centers, six full-time FBISD mental health counselors serve every campus in the district, and outside counselors also offer services at select schools.

“There used to be one therapist per campus,” Avantsa said. “Now, one therapist can serve multiple campuses, so we are spreading our wealth.”

The services are part of the district’s larger vision to support the health and well-being of the whole child—meaning to not only meet the child’s academic needs, but also their physical and social-emotional needs.

Education experts said schools play a vital role in providing wraparound services to vulnerable students. Having mental health resources on campuses reduces barriers to accessing care, said Pilar Westbrook, FBISD executive director of social emotional learning and comprehensive health, during a March public hearing.

Since the pandemic began, the levels of social anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation in school-age children have increased, said Angela Koreth, a child and adolescent counselor at The Menninger Clinic. Koreth said The Menninger Clinic, which provides inpatient and outpatient treatment for mental health disorders in Houston, saw rates of anxiety and depression among inpatient adolescents increase approximately 35%.

“We’ve seen three areas that the pandemic has impacted school-aged kids: academically, socially and mental health,” Koreth said. “In the mental health field, there’s been increases in anxiety and depression—lots of sleep and nightmare issues. And for adolescents, there’s been an increase in suicidal ideation and grief and trauma.”

Pandemic pains

The need for the services was in part driven by rising rates of suicide and homicide ideation and as reported in at-risk assessments, said Steve Shiels, director of behavioral health and wellness at FBISD.

From August 2020 until May 24, 111 FBISD students were identified as “high risk,” 126 as “medium risk,” and 323 as “low risk” for suicidal ideation, according to district-provided data. When the pandemic closed schools in March 2020, Avantsa described shifting mental health services to virtual as a baptism through fire.

“We tend to be more face-to-face,” Avantsa said. “It’s about building relationships, getting to know your kids, and relationships get built through physically being with people, so we really had to change a lot.”

Most FBISD students will return to school face-to-face in the fall. Koreth said this will be a big adjustment for some students, exacerbating issues such as social anxiety and academic gaps.

“There’s going to be some grief and trauma that adolescents are going to have to deal with and schools are going to have to deal with. Kids have been through a lot,” Koreth said. “But kids are resilient, and if we can ... show them we’re a caring environment, caring school, caring counselors, caring teachers—that will help them along with this process.”

David Sincere Jr., the pastor of Fort Bend Transformation Church in Missouri City, said his daughter had a mental health crisis six years ago. He described it as an everyday fight to get his daughter the help she needed.

“I commend Fort Bend ISD for offering these services for our families and most importantly our children,” Sincere said during the public hearing. “I wish Fort Bend ISD offered these services for my daughter. Thank God they offer them now.”

Scope of services

FBISD’s six full-time, district-employed mental health counselors each serve two high school feeder patterns with one serving a single feeder pattern and Spanish-speaking families, said Jesse Moreno, a mental health counselor for FBISD.

The district also partners with two outside organizations—Clearhope Counseling and InvoCare—to provide additional mental health care in the school setting. Clearhope Counseling provides services on 22 campuses, while InvoCare serves nine.

Avantsa said the district’s counselors support families without insurance, while partners typically serve families with insurance or those who qualify to have services covered through federal funding. Additionally, students at schools not served by a partner can still be referred to the partner for counseling, but it will be provided at a partner’s office or via telehealth.

“We don’t want any of our kids to fall through the cracks,” Avantsa said.

FBISD plans to add two additional mental health partners at the beginning of the 2021-22 school year. Sugar Land Counseling will provide campus based services at five additional schools, while Texas Child Health Access Through Telemedicine will focus on crisis intervention efforts throughout the district, Avantsa said.

“Every high school in our district has a mental health community partner, and by the beginning of next year we will have all our middle schools having a community partner as well,” Avantsa said.

The board approved FBISD to apply for a third year of federal funding for the services through the 1984 Victims of Crime Act in March. If awarded, the $394,000 grant would begin in October.

Under the VOCA grant, students who have been victims of crime are eligible for no-cost mental health services. Avantsa said the grant has an expansive definition of crime—whether it is reported or not—including any kind of abuse, harassment, bullying, substance use, domestic violence in the family or witnessing a crime. A majority of students receiving mental health counseling and therapy through FBISD are doing so under the VOCA grant, Avantsa said.

While the six mental health counselors are employed through the district, FBISD said services provided by partner counselors are free to the district—fully funded through grants, the family’s insurance or self-pay.

Leading up to the March hearing, members of the community expressed privacy concerns. Still, FBISD said most feedback has been positive.

“As a counselor when I get that phone call from a parent, and they have a crisis on their hands, ... and I’m able to remedy that situation for them, that sigh of relief, ‘OK, my baby’s going to be fine,’ is something that you just can’t match,” said Taheera Shelton, a counselor at Hodges Bend Middle School. “Initially people feel some kind of way, but when their child is able to get that service that they otherwise would not have probably got or not know how to have gotten—it’s a good thing.”