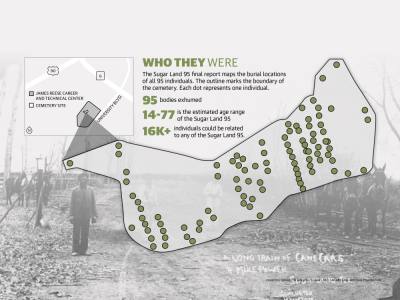

Construction on the $59 million James Reese Center eventually hit its target completion date ahead of the 2019-2020 school year. But the discovery of the remains—94 men and one woman—unearthed a slice of Sugar Land’s history that ignited conversations about how best to memorialize these people and educate the public on the convict labor leasing program, according to officials from Fort Bend ISD, which owns the land where the bodies were uncovered.

“It’s an extraordinary discovery,” FBISD Chief Operations Officer Oscar Perez said. “It’s a part of history that has been untold. Since the discovery of the first bone until now, I know more about convict leasing than I ever knew.”

With one eye on the past and the other on the future, Fort Bend ISD has rolled out the first steps to its Sugar Land 95 Memorialization Project. The project is designed to properly recognize the 95 individuals—all who are suspected of being Black and dubbed the Sugar Land 95—and stimulate community and student discussions on the convict leasing program and Sugar Land’s past role in that program, said Chassidy Olainu-Alade, the district’s coordinator for community and civic engagement.

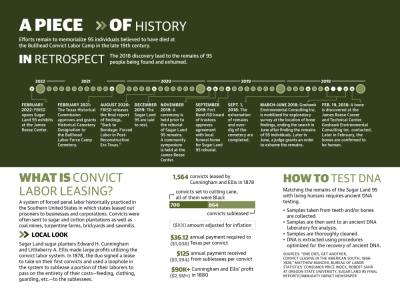

Convict leasing was a system of forced penal labor historically practiced in the Southern United States in which states leased out prisoners to businesses and is seen by experts as an extension of slavery.

Proper recognition

The district’s memorialization project began with the discovery of the first human remains in February 2018, Olainu-Alade said.

The project has taken a three-pronged approach to restoring dignity to the Sugar Land 95, she said.

“Education, obviously, is the first facet of the memorialization project,” Olainu-Alade said. “We’ve really invested a lot of our time and energy on advancing education and awareness not only of the discovery, but the system of convict leasing statewide and nationally.”

As a part of this educational component, an exhibit for the general public detailing the story of the Sugar Land 95 opened in February at the James Reese Career and Technical Center.

One part of the exhibit highlights the history of convict leasing in Texas, while another focuses primarily on the discovery, scientific research and forensics that went into providing an accurate account of what occurred on the property, Olainu-Alade said.

Since the exhibit’s opening, Fort Bend ISD has been hosting public tours three times per month along with private tours. In March, the district hosted five private tours. Because demand has been so high, the district increased the number of public and private tour slots, Olainu-Alade said.

“It really says that people are eager to learn,” she said.

The exhibits are just one way the district is improving student education on the convict leasing system.

In May 2019, for example, the FBISD board of trustees adopted a locally developed social studies standard related to local history associated with the Sugar Land 95 and convict leasing. The standard has allowed teachers to incorporate instruction related to that history, according to a district announcement.

This joins broader efforts by the Texas State Board of Education to bring more African American studies into the classroom. In April 2020, the board approved an African American studies elective for high schoolers that includes information regarding convict leasing and the Sugar Land 95.

Meanwhile, the second and third prongs of the district’s project target memorialization and community engagement, Olainu-Alade said.

Memorializing the 95 individuals who still reside in a cordoned-off cemetery space adjacent to the James Reese Center revolves around installing a kind of outdoor learning plaza. However, what form that takes and the details, costs and timeline of that project depend heavily on what design arises from the ongoing community engagement sessions.

The sessions are led by Massachusetts architectural firm MASS Design, which has designed dozens of high profile memorials, including The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

“How do we convert the environment into a space that is conducive to honoring, restoring dignity, and learning at the same time about the system of convict labor and the victims of convict leasing?” Olainu-Alade said.

Discovery

On Feb. 19, 2018, Daniel Diaz, a backhoe driver on the James Reese Center construction site, uncovered a human thigh bone.

The district had hired Goshawk Environmental Consulting Inc. to investigate the 23-acre site for the upcoming CTE Center, but it had found no evidence of bone remains when it scoured the area between October 2017 and January 2018, said Reign Clark, the consulting firm’s archeological project manager at the time.

When Clark received an email from a colleague about the bone discovery, he said he was certain that they had come across human remains.

“I was thinking to myself as I looked at the photos that there was a 95% chance that what I was looking at was human,” Clark said. “I had moved entire cemeteries before, and I had seen a lot of human bone fragments, and to me it was the right size and shape to be human.”

To district officials, however, the discovery was not a complete surprise, Perez said. The district had been tipped off for years by Reginald Moore, the late community activist and convict leasing historian. He warned FBISD administrators of the possibility of remains being discovered at the James Reese construction site because it had formerly been the Bullhead Camp between 1880-1910.

By August 2018, the exhumation and reinterment of the 95 bodies was complete, though conversations on the convict leasing system and Sugar Land’s role in that system remained.

The convict leasing system, used to help Southern states supplement their depleted treasuries in the wake of the Civil War, was not unique to Sugar Land nor Texas despite the cruelty it inflicted on its prisoners, said Matthew Mancini, chair of the Department of History at Southwest Missouri State University. Mancini is also the author of the 1996 book “One Dies, Get Another, Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866-1928.”

“The states were the lessors, and the businesses and corporations the lessees, and they leased these prisoners,” Mancini said. “The states were completely uninterested in having anything to do with prisoners. They gave the prisoners to the businesses, and they could do anything they wanted with them. The whole point for the state was to avoid any expenditure.”

In 1878, Sugar Land business owners Edward H. Cunningham and Littleberry A. Ellis signed a lease to take on 1,564 convicts, according to Mancini’s book. Of those, 700 were assigned to cut sugarcane; the rest were subleased out for major profits, according to Mancini’s book. According to Mancini, it’s unclear how many convicts were assigned to the Bullhead Camp.

Though Texas may have held the lowest proportion of Black people among its prison population—about half—that did not change the convict leasing system’s status as a brutal, race-based system, Mancini said.

According to both Mancini and Robin Cole, president of civil rights group The Society of Justice & Equality for the People of Sugar Land, many Black men were arrested for trumped-up charges and put in the convict leasing system.

“So they came up with things that would be considered to be a crime,” Cole said. “If you walked on the wrong side of the street, if you were unemployed, if you were an orphan, if they said, ‘Oh, you’re out past the curfew. That’s $10. And now you’re a criminal because you can’t pay that $10.’”

Looking forward

With the exhibit open at the James Reese Center, the Sugar Land 95 Memorialization Project will involve students more fully, Olainu-Alade said.

FBISD is planning on ways to train students to become docents or tour guides through summer sessions and workshops. Should the plan go forward, students would be tour guides beginning in the 2022-23 school year, Olainu-Alade said.

This comes as MASS Design is halfway through hosting community engagement sessions on the future outdoor learning plaza and memorial space. According to Olainu-Alade, the last session is scheduled for May 25.

Through those community engagement sessions, MASS Design should have a final design rendering ready for the public by late summer or early fall.

“I would like to see [a] way for them to find out who is in what unknown gravesite,” Cole said. “Let’s work together and raise money so we can find out who these people are. I would also like a design that would allow people to come and be able to pray or meditate with something like a bench that would allow people to pray for their souls. Also, maybe have a statue in the middle. Something positive.”

Using historical documents from the Texas State Penitentiary and death records from Fort Bend County, researchers have compiled a list of 71 men who worked and died at the Bullhead Camp between 1879-1909. However, further ancient DNA analysis—a process through which a DNA test connects a living descendent to the discovered remains and works backward using genealogical records—is necessary to match those names to individual remains found at the cemetery, according to the Sugar Land 95 final report, which was released in August 2020.

Through a partnership between the University of Connecticut and Othram Inc. in The Woodlands, 14 ancient DNA sample extractions from the site will be sequenced over the next two months to help identify 14 individuals, Clark said.

The remaining test samples, however, require more than $50,000 in funding before the sequencing can be completed.

“We need funding,” Clark said. “We desperately need funding to perform that sequencing.”