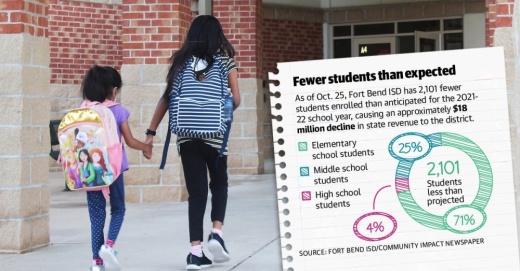

As such, Fort Bend ISD’s demographers projected student enrollment to largely rebound during the 2021-22 school year. However, 77,600 students were enrolled as of Oct. 25, which is 2,101 students short from the district’s projected enrollment of 79,701—a gap widely attributed to the pandemic.

Texas school districts receive the bulk of their funding from local property taxes and the state, which allocates funding based on average daily attendance. Because FBISD built its fiscal year 2021-22 budget around higher projected enrollment numbers, officials expect the district to receive about $18 million less from the state than anticipated, Chief Financial Officer Bryan Guinn said.

“This year, enrollment didn’t materialize, and so [the state is] going to start paying us based on our lower enrollment number,” Guinn said.

Chandra Villanueva, economic opportunity program director at Every Texan, said not everyone feels safe sending their kids back to school. Every Texan is an Austin-based nonpartisan group focusing on public policy.

“You have parents on both sides who have issues and concerns about [sending their kids back],” she said.

To make up the financial gap, Guinn said FBISD may have to dip into federal dollars allocated for COVID-19-related expenses—funds largely set aside to combat learning loss.

“The [State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness] test scores are very indicative of the fact that learning loss has occurred and is very real,” Guinn said. “Any funding we don’t have available to address that learning loss is going to put students at a disadvantage.”

Enrollment below projection

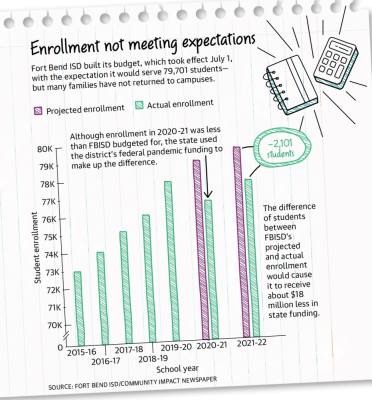

Before the pandemic, FBISD was growing. From the 2015-16 school year to the 2019-20 school year, FBISD’s student enrollment grew more than 6%, according to Texas Education Agency data. The district was expected to educate more than 87,700 students by 2030-31, according to the predictions made in March by Population and Survey Analysts, the district’s demographers who track birth rates, housing and the local economy to project enrollment for school districts.

However, enrollment growth has since paused, Guinn said. During the 2019-20 school year, FBISD had an enrollment of 77,756 students, according to TEA data. Although PASA projected FBISD would serve 79,076 students in 2020-21 and 79,701 students in 2021-22, enrollment was 76,735 in 2020-21. So far, 77,600 students are enrolled for the 2021-22 school year—2,101 less than projected, district data shows.

“What we’re seeing is the enrollment that was projected is not materializing,” Guinn said. “If you look year over year, our actual enrollment has stayed essentially flat from the [20]19-20 school year.”

Most students who did not enroll in 2020-21 and 2021-22 are elementary-age students in pre-K through second grade, officials said. Of the 2,101 missing FBISD students, 71%—or 1,500—are elementary age, according to data from the district.

Monty Exter, a senior lobbyist with the Association of Texas Professional Educators, said many parents of children in the earliest grades have decided to keep their students out of school until the pandemic is over. He also said parents who opted out of pre-K and kindergarten last year may continue to do the same this year.

“A lot of folks are saying, ‘We’re going to simply hold our kids out a year,’” Exter said. “They’re saying, ‘They’re young enough that once we get past [the pandemic] we’ll re-enroll them, whether that’s enrolling them in first grade or enrolling as a kindergartener who’s a little older than they otherwise would have been.’”

Ripple effects

While it is too early to see the long-term consequences of skipping pre-K and kindergarten, Villanueva said she is concerned about students missing these developmental years.

“Those are the formative years where you’re learning the basics of how to learn [and] how to read [as well as] social-emotional things,” Villanueva said. “There [are] a lot of things that happen and are important in those early grades for setting up a foundation that I do have concerns that children are missing out on.”

Guinn said FBISD is not seeing its students enroll in other school districts, charter schools or private schools, leading officials to believe most of the missing students are being home-schooled.

“We feel strongly that [these students] are out there,” Guinn said. “But at the end of the day, they have not come through the doors.”

Still, Guinn said unlike last year, some districts are seeing enrollment materialize in the 2021-22 school year. He said Lamar CISD has seen a similar pattern as FBISD, but enrollment in Katy ISD is at or above projections.

The latest projections from PASA—which were presented to the FBISD board of trustees in March—show enrollment continuing to recover after the pandemic, nearing 82,000 students by 2022-23. However, Exter said it is too early to tell whether COVID-19’s effect on enrollment will last beyond this year.

“Whether or not ... folks continue to be in that homeschool environment once the COVID[-19] issues have passed, we don’t have a way of knowing that right now,” Exter said.

Making up the difference

Because districts are funded for average daily attendance, both enrollment declines and lower attendance rates affect how much money a district gets from the state.

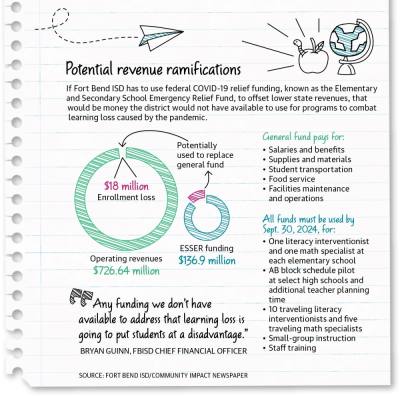

For the fiscal year 2021-22 amended budget, FBISD projected a total of $726.64 million in operating revenues, based in part on state funding and property tax revenue. If the district’s enrollment remains approximately 2,101 students below projected, the district would lose out on about $18 million in state funding this budget cycle, bringing its operating revenue to $708.64 million, according to district documents.

Last school year, the TEA automatically used districts’ federal coronavirus relief funds to offset enrollment declines. Called “hold harmless,” this supplanting of revenue used Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funds from the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act—known as ESSER II—to fund districts where enrollment was less than projected.

“Yes—we received revenue in the general fund that is specific to holding us harmless for that enrollment loss,” Guinn said. “[But], we were shorted by roughly $9.2 million that would have otherwise come ... as part of ESSER funding that we’d have to address learning loss.”

So far, neither the TEA nor the Texas Legislature has signaled it would enact a similar provision this year. Villanueva said as more districts realize enrollment is down, there may be more calls for it.

“I expect we’re going to start hearing more and more calls for some sort of hold-harmless funding ... so that [districts] don’t have to dip into their own individual allocations,” she said.

Still, Guinn said FBISD may have to use some of its $136.9 million of ESSER II funding or ESSER III funding, which was allocated under the American Rescue Plan Act, to counter revenue shortfalls caused by the enrollment deficit.

At the same time, districts are trying to use their ESSER funding for both locally-initiated and state-mandated interventions to combat learning loss.

FBISD previously outlined a plan to use its ESSER II and III funds for interventions, including additional teacher planning time, staffing costs, and small group instruction, in addition to pandemic expenses, Chief Academic Officer Beth Martinez said.

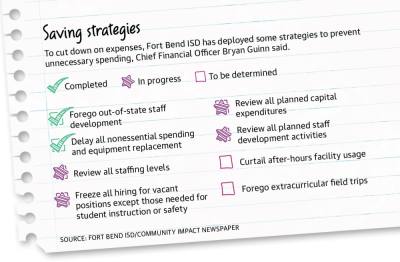

FBISD has worked to reduce spending, including reviewing staffing levels, freezing most hiring, pausing out-of-state staff development and delaying all nonessential spending, Guinn said during a Sept. 20 meeting.

“We feel like between making the expenditure adjustments and looking at staffing, we should be able to control that number and not have to tap into ESSER,” Guinn said. “But, worst case scenario, we do have ESSER as that backstop.”

If the district does lose about $18 million in ESSER funding due to enrollment loss, Martinez said FBISD may have to cut back on its planned interventions.

“It’s not easy decisions that districts have to make, but it is really unfortunate that they’re being put in that situation by the state,” Villanueva said.