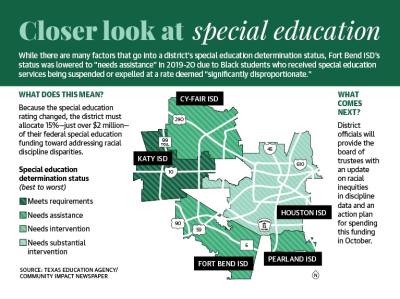

This disproportionality affected FBISD’s special education determination status in the 2019-20 school year as the Texas Education Agency determined Black students receiving special education services were disciplined at a rate deemed “significantly disproportionate.”

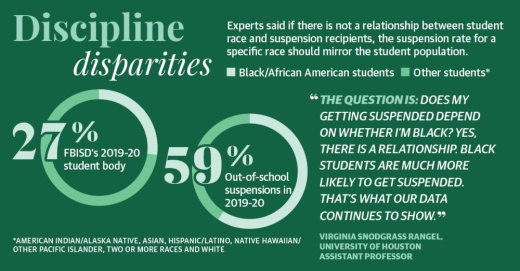

TEA data shows Black FBISD students are disciplined at a rate disproportionate to their representation in the student population—a trend mirroring districts across the state and nation, experts said. In the 2019-20 school year, Black students made up about 27% of the district’s student population but received 59% of out-of-school suspensions that year.

Vicky Sullivan, a senior staff attorney with the Education Justice Project at Texas Appleseed, a social, economic and racial justice nonprofit, said reforming school discipline practices is especially important in the wake of the pandemic and murder of George Floyd—two events she said revealed systemic racial inequities.

“There is an urgent need to transform how we see school discipline in public education—one that acknowledges and confronts the ingrained inequities and systemic barriers that result in further marginalizing some students,” Sullivan said. “How we achieve that—that’s the million-dollar question.”

In the past five years, the district has implemented strategies to combat racial disparities in discipline, including training teachers on trauma-informed care and restorative—rather than punitive—practices, district officials said.

“We can’t necessarily change the way kids are going to behave, [but we can] try to provide more training and understanding for our staff so that they can respond safely ... and then try to de-escalate the situation,” said Deena Hill, FBISD’s executive director of student support services.

Extent of inequality

Racial disparities in discipline data can be found in nearly every school district in Texas, Sullivan said.

In the 2019-20 school year, Black students in Texas made up 13% of all students but accounted for 31% of out-of-school suspensions, according to TEA data. A November 2020 report from The Education Trust, a national education advocacy group, showed Black students are five times more likely to receive out-of-school suspensions than their white peers. Horace Duffy, a research specialist at Houston ISD whose doctoral degree in sociology focused on student discipline, said race is a factor in the likelihood of a student’s suspension.

“We know that there is a racial bias, and that Black and Latino students are not inherently more deviant than white and Asian students,” he said. “The research bears that out.”

Out-of-school suspensions are particularly problematic because they remove students from school entirely and increase their risk of coming in contact with the juvenile justice system, Duffy said.

TEA data from 2015-16 shows while Black students made up about 28% of FBISD’s student body, they received 67% of all out-of-school suspensions. Since then, the percentage of out-of-school suspensions given to Black students declined to 59% in 2019-20. Hill said FBISD did not issue suspensions to students learning remotely in the last nine weeks of the 2019-20 school year or during the 2020-2021 school year due to COVID-19.

All of FBISD’s students began the 2020-21 school year remotely and about 48% of students returned to campus by the end of the year, reducing the number of out-of-school suspensions from 2,460 in 2019-20 to 616 in 2020-21, according to district and TEA data. Black students received about 51% of the suspensions given in 2020-21.

“The student discipline numbers may have decreased in the virtual setting, but the disproportionate overrepresentation of harsh, punitive and exclusionary discipline administered to Black and brown students was still present,” Sullivan said.

Contributing factors

Experts said causes for racial inequities in discipline can vary, but stem from structural racism, in addition to unconscious bias in teachers and administrators.

Structural causes for racial inequities in disciplinary practices occur when codes of conduct single out students from a certain ethnic or racial group, said Virginia Snodgrass Rangel, an assistant professor in the department of educational leadership and policy studies at the University of Houston.

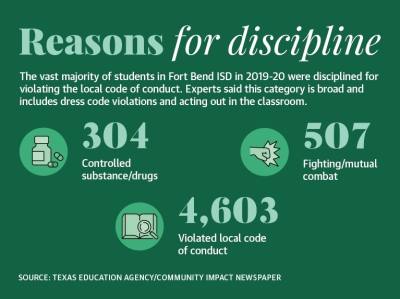

In 2019-20, 4,603 FBISD students were disciplined for violating the local code of conduct, exceeding fighting—the next most common reason for discipline—by more than 4,000 incidents, TEA data shows.

FBISD’s student code of conduct classifies misconduct as dress code violations, tardiness, vandalization, cheating, bullying, possessing prohibited items and other actions.

District officials said differences in experience and culture among staff is a root cause of the disproportionalities. Duffy said while diversifying the teacher population so that it more closely mirrors the student body’s demographics can help reduce the racial disparity in discipline, it will not solve broader systemic issues.

In FBISD, 16% of students are white, but 43% of teachers are white. Black teachers account for 32% of teachers and Black students are 27% of the student population. Asian and Hispanic or Latino teachers are also underrepresented compared to the student body.

“The culture where you grew up, what you understand, is going to impact the decisions you make with discipline,” Hill said.

A decreased special education rating

The disparity has also affected the special education determination rating for the district. In the Texas Academic Performance Report, the district’s special education determination status went from the highest level of “meets requirements” in 2018-19 to the second-highest level of “needs assistance” in 2019-20.

The determining factor for the district’s special education status was its “significantly disproportionate” rate of out-of-school suspensions black students receiving special education services were given, Hill said.

Because the district’s status went down, Hill said FBISD is required to set aside 15% of its federal special education funding—over $2 million for the 2021-22 school year—to address the issue until the rating improves.

District officials said for the 2021-22 school year, they have created an intervention plan with district and campus leadership to address the problem of discipline discrepancies.

Hill said more information about racial disproportionality in discipline will be presented at the October board meeting. Administration will also propose spending targeted funds to hire instructional coaches who will work with teachers to address disciplinary practices at select campuses.

“We’ve already developed a plan and are implementing that plan as we go forward into this school year with the hopes that with the additional money in that targeted area we’ll see improvements,” Hill said.

Alternative solutions

Snodgrass Rangel said districts should reduce the overall number of kids who are suspended and the racial disparities in suspensions given.

After the coronavirus pandemic led to learning loss among a wide cross-section of students, a 2021 report from Texas Appleseed called for banning disciplinary practices—such as suspensions and expulsions—that remove students from the classroom.

“Districts need to retool and reinvent their disciplinary system such that they’re forward-thinking, progressive, inclusive and restorative—with training and awareness of implicit bias,” Sullivan said. District officials said FBISD has implemented restorative practices and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports—two alternatives to punitive disciplinary measures. Under PBIS, students are taught behaviors they should display with positive reinforcement, said Sarah Morvant, FBISD’s assistant director of behavioral health.

In restorative practices, teachers talk to students about the behavior, its cause and possible consequences, district officials said.

Educational experts said data shows PBIS and restorative discipline work—but are time-consuming and costly.

“We have good answers ... to address these issues, it just takes the resources and the will to make these changes,” Snodgrass Rangel said. “It’s not easy, but I think our kids deserve it.”