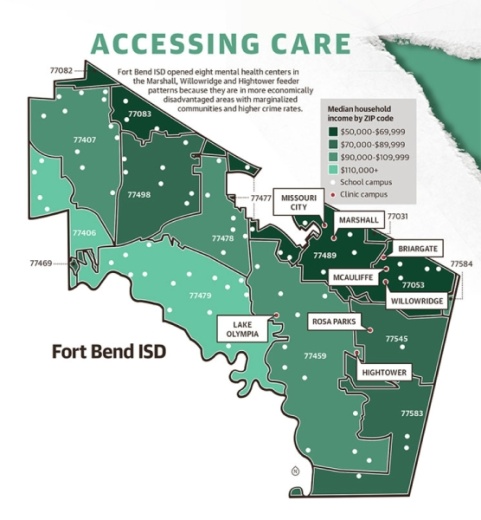

The centers—located at Hightower, Marshall and Willowridge high schools; Lake Olympia, Christa McAuliffe and Missouri City middle schools; and Rosa Parks and Briargate elementary schools—are funded by a $1.5 million grant awarded under the 1984 federal Victims of Crime Act.

Steve Shiels, FBISD’s director of behavioral health and wellness, said by opening these clinics the district is taking a big step in addressing the mental health needs of school-age children, the stigma around mental health and school safety concerns.

“Data shows that in the last five years, the mental health needs of students were just really beyond the scope of what a school was able to deal with well, and that it was a really big challenge for students who are not getting the support that they needed,” Shiels said.

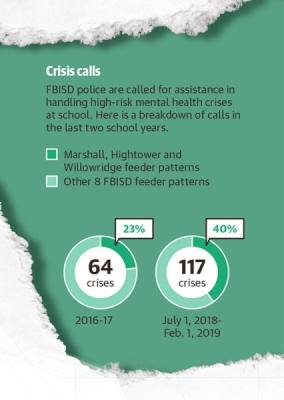

Over the last three school years, FBISD has seen an increase in the number of calls to the FBISD Police Department for assistance handling high-risk mental health crises at school, according to the district’s application for the VOCA grant, which Community Impact Newspaper obtained through a public information request.

In the 2017-18 school year, district police responded to 68 high-risk mental health crises, with 52% of them occurring in the Hightower, Marshall and Willowridge feeder patterns, the feeder patterns with clinics. Additionally, from July 1, 2018, to Feb. 1, 2019, there were 117 calls, with 40% occurring in the identified feeder patterns.

Choosing clinic locations

FBISD chose the locations of the first clinics because they are in historically marginalized communities with high crime rates, according to the district’s VOCA grant application.While FBISD confirmed in their VOCA application that there is a high demand for mental health services across all 11 of its feeder patterns, it said the demand is especially high in the Hightower, Marshall and Willowridge feeder patterns.

“Those feeder patterns were showing the highest [need] consistently, so that was the reason for that choice,” Shiels said.

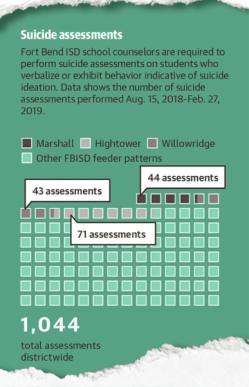

Of the district’s 1,044 suicide assessments, 158 were performed in the Hightower, Marshall and Willowridge feeder patterns. School counselors conduct these assessments on students who verbalize or exhibit behaviors indicative of suicide ideation.

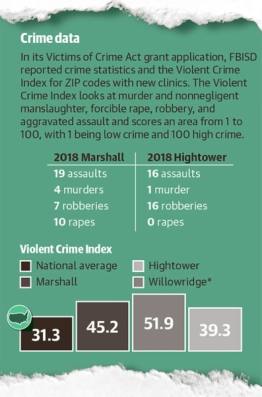

The district’s application also provided the Violent Crime Index—which looks at murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault in an area—for three of the four ZIP codes with clinics. All three ZIP codes had a higher Violent Crime Index than the national average.

U.S. Census Bureau data shows that the ZIP codes where clinics are located had, on average, lower median household incomes. Additionally, district data showed the average percentage of economically disadvantaged students, or those who qualify for free and reduced-price lunch, in the Hightower, Marshall and Willowridge feeder patterns is 76%, whereas the district average is 43%.

Students, families and district employees who have been victims of crime are able to access services at no cost. Shiels said the grant has an expansive definition of crime and that those who do not qualify for free services can pay using insurance or Medicaid.

Mandi Kimball, director of public policy and government affairs with Children at Risk, a Texas-based research and advocacy organization, said trauma can be experienced in many ways including crime, abuse, neglect and hunger, and that trauma of all kinds affects students at school.

“We know the juvenile justice system is the No. 1 mental health provider, and what Fort Bend ISD is trying to do is to stop that continuum and make sure students get the services they need so that they can be successful in school and life,” Kimball said.

Shiels said the district recognizes there are mental health needs regardless of socio-economic status.

“There are clearly mental health issues at all of our campuses that need to be addressed,” Shiels said. “So, the plan is pretty quickly to start expanding, and to expand outside of those three feeder patterns, and to expand more west.”

Seeking services

FBISD is modeling its clinics after Austin ISD’s School Mental Health Centers, a program AISD started in 2011. Like AISD, FBISD is partnering with Vida Clinic to staff the centers with licensed therapists.Laura Rifkin, the director of program development at Vida Clinic, said Vida clinicians see many mental health challenges in school-aged students.

“We approach [school-based mental health] through an ecological lens, which means we’re really looking at all of the systems that impact our young people in the school ... so ... we’re also able to provide therapeutic services for their family members, as well as for staff in the school,” Rifkin said.

Tracy Spinner, AISD’s director of comprehensive health and mental health, said AISD has seen improvements in students’ mental health outcomes, academic performance and discipline since opening its clinics. Data shows AISD students who received mental health services had an attendance rate of 94.65%, 2 percentage points higher than a control group.

“When we begin to really look at this data, it’s powerful,” Spinner said. “And this data held true for elementary, middle and high school.”

Shiels said school counselors will facilitate mental health referrals from concerned school staff, teachers, social workers, parents or the student themselves. Before Vida Clinic therapists can administer services, the parent and student will participate in an intake process where students will be evaluated and their course of treatment will be determined.

Shiels and FBISD trustee Kristin Tassin said having clinics directly on campuses combats the stigma around mental health, improves school safety efforts and reduces barriers to mental health resources.

“I think the ideal is to have [clinics] in the school, so there’s this acceptance of mental health,” Shiels said.

Tassin said she hopes the centers reach the right students.

“To me, success would be being able to find students [that need services], and then being able to support those students and help those students as they try to work through these challenges,” Tassin said. “And then help them to get educated and give them an opportunity to have a successful future.”