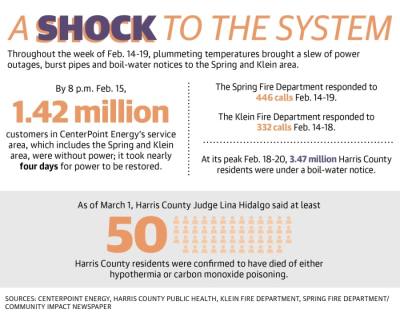

Boil-water notices during and after Winter Storm Uri were rampant in Harris County, with 3.47 million county residents under a boil-water notice Feb. 18-20, according to Harris County Public Health.

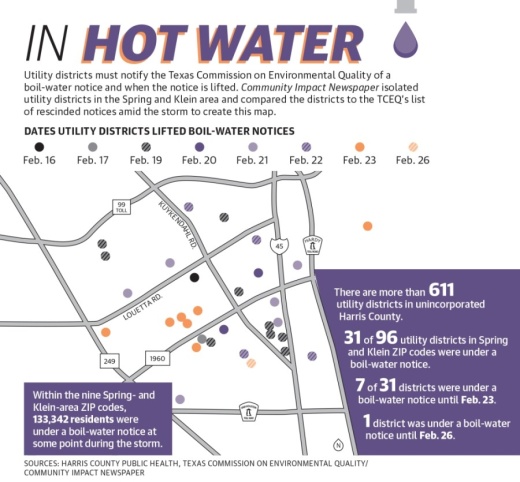

Although the city of Houston was able to lift its boil-water notice on Feb. 21, notices remained in place for thousands of residents in unincorporated Harris County. Within the nine Spring- and Klein-area ZIP codes, 133,342 residents were under a boil-water notice at some point during the storm, according to data Community Impact Newspaper compiled from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

As notices were lifted, local water authorities and city of Houston officials said the responsibility of informing consumers on when it was safe to use water was on local utility districts and residents themselves. This resulted in some business owners and residents in unincorporated Harris County unsure if the city’s notice pertained to their property, Michael Schaffer, HCPH’s director of the environmental public health division, said via email.

"When the city of Houston lifted their boil-water notice, some constituents did not understand how [the] water system worked. Some constituents assumed—wrongly—it applied to the entire county,” he said.

Boil-water notices

When temperatures dropped, some Houston-area residents turned off their water or dripped faucets, which dropped the area water pressure to 20 pounds per square inch. In response, Houston issued a boil-water notice Feb. 17 for its main water system, according to city of Houston news releases.

Consumers in Houston and some outlying areas receive water from the main system, which stems from Lake Houston. Most residents in unincorporated Harris County, however, pay water usage fees and infrastructure costs to utility districts, which pay pumping fees to regional water authorities to use pump stations and surface water transmission lines from Lake Houston.

The North Harris County Regional Water Authority, which distributes water to 160 utility districts, including those in the Spring and Klein area, is one of several water authorities that source water from purification plants in the main system. Shortly after the city issued a notice, the authority also issued a boil-water notice because the Northeast Water Purification Plant was unable to provide more than a “fractional amount” of surface water, according to NHCRWA news releases.

As the city’s notice lifted Feb. 21, Erin Jones, public information officer at Houston Public Works, said water authorities and utility districts needed to determine if water met their quality standards before lifting their own notices—despite the news release not including that caveat.

Jones said the city could not speak for other entities and would not issue or recommend boil-water notices for those outside the city’s main system. She said the responsibility falls on consumers and utility districts.

“I would think that hopefully businesses and customers would be able to identify ... where I’m paying my water bills [to],” she said.

NHCRWA President Al Rendl said many utility districts the authority distributes to switched to power generators or groundwater pumps when Houston’s pressure dropped. Those that could not switch had to issue boil-water notices to their consumers, Rendl said.

When the NHCRWA lifted its boil-water notice Feb. 22, Rendl said utility districts needed to independently confirm the water was safe and issue notices.

Confusion, education

After Houston lifted its boil-water notice, Schaffer said that Harris County Public Health sent out 31 staff members to 1,018 businesses in unincorporated Harris County to ensure boil-water notices were being observed.

Schaffer said he believes all residents, including those in unincorporated Harris County, need to know how their water relates to the larger water system. He said it is easier for Houston to notify residents than Harris County to notify unincorporated areas.

“It is a challenge for the residents that reside in unincorporated areas [of] Harris County that rely on over 611 water systems to know which they belong to,” he said.

To help in this effort, HCPH launched an interactive map on readyharris.org and the HCPH website showing the utility districts under boil notices and where notices were lifted.

Some businesses, such as Tumble 22 in Vintage Park, continued boiling water. Tumble 22 General Manager Doug Lyons said he knew his eatery was in Municipal Utility District No. 468 and still needed to boil water, allowing the business to operate and follow safety and sanitary requirements.

“Unfortunately, when Houston put out that notice that they were no longer under a boil notice, ... there was almost a million people still under boil notice, and everyone just started using their water again,” he said.

Tumble 22 stopped boiling water Feb. 23, when HCPH’s interactive map showed MUD 468’s boil notice was lifted. While Lyons said Vintage Park’s engineer relayed updates on water quality from MUD 468, he said he does not believe he would have known had he not learned about the utility district when the eatery was preparing to open in December.

“Since I had dealt specifically with that municipal [utility] district during our inspection process not but four months ago, I was intimately aware with which water district we were part of, so it made it easier for me to do it,” he said. “There was no real, clear-cut communication ahead of time, as far as I saw, [for] who was responsible for what.”

Awareness for future events

Notifying consumers during an emergency can sometimes be difficult for utility districts, said Auggie Campbell, executive director of the Association of Water Board Directors—Texas, which educates water board directors on caring for communities.

By law, utility districts are only required to post boil-water notices at its local building and notify the county and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, Campbell said. Counties are not required to relay the notices to the community, he said.

“The way [a lot of MUDs] communicate with their customers is their bill, ... and that doesn’t really do much during an emergency,” he said.

For utility districts in the NHCRWA’s boundaries, Rendl said districts are not capable of notifying each individual that the district is on a boil notice, especially with icy roads and lack of internet connection.

“Everyone was quite aware of the problems we were having but were, in many instances, frustrated in their ability to let every person know,” Rendl said.

For the same reasons, the storm could have also made it more challenging for consumers to find notices from utility districts if they could not leave their homes, Campbell said. However, he said he believes the TCEQ could be the official real-time source for future water notices.

“It’s important for customers to look at their bill and know what MUD they’re in, but I do think that there are opportunities for districts and for the TCEQ ... to make it easier so people understand where they get their water from and how to make sure that it’s safe,” he said.