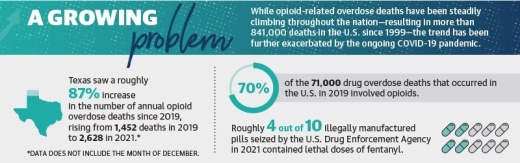

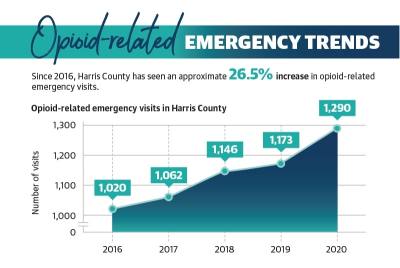

Opioid overdose deaths have steadily climbed in Texas, rising from 4,154 deaths in 2020 to 4,831 deaths in 2021, according to the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics. Provisional NCHS data indicates there were an estimated 100,306 drug overdose deaths in the U.S. in 2021, an increase of 28.5% from 2020.

In Harris County, the number of drug overdose deaths similarly rose from 840 deaths between October 2019 and September 2020 to 1,039 deaths that occurred in the following 12 months, according to NCHS provisional data.

“These are diseases of despair that we’re dealing with,” said Tyler Varisco, a health services researcher with the University of Houston. “When people are economically challenged or psychologically challenged, ... we see increased vulnerability in our communities to opioid use and other forms of substance misuse.”

Legally obtained prescriptions

In the late 1990s, pharmaceutical companies began marketing prescription opioid pain relievers as drugs that were not as addictive as previously thought, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Doug Hooten—CEO of Harris County Emergency Services District 11 Mobile Healthcare, which provides emergency medical services across 177 square miles in Harris County, including Spring and Klein—said many people who get addicted to opioids first experience them with legally obtained prescriptions.

“These are people who have legitimately been injured and doctors who have legitimately given them medications to help them get over their injury,” Hooten said. “Once they can’t get a prescription anymore, they’re subject to having to find another source. That leads to opioids, to heroin, to meth.”

In recent years, doctors have become more aware of the potential dangers of prescribing opioid-based drugs, said Dr. Ericka Brown, director of Harris County Public Health’s Community Health and Wellness Division, which oversees the countywide Opioid Overdose Prevention Program.

In 2010, physicians administered 69.1 opioid-based prescriptions for every 100 residents in Harris County, according to the Centers for Disease Control. By 2020, the county’s opioid dispensing rate had fallen to 37.8 prescriptions per 100 residents.

However, Varisco, who trained as a pharmacist at The University of Texas, said unnecessary prescriptions have yet to be addressed for pharmaceutical students.

“This crisis has exposed cracks in the system and made them a lot more evident,” Varisco said.

With opioid dispensing rates falling over the last decade, Brown said HCPH’s focus has since shifted to illegally obtained opioids.

“Now, the [production] of ... lookalikes of prescription medication, I think, is overtaking the prescription medications themselves,” Brown said.

Illegal pill manufacturers

Many opioid overdose deaths result from individuals procuring drugs made by illegal pill manufacturers with no knowledge of what they may contain, according to Hooten.

“They look like the pills that you would get from a pharmacy, but they’re not, and the quality of that and the quantities of stuff that you’re taking is unknown,” Hooten said. “It’s just Russian roulette.”

Hooten said illegally manufactured pills often contain fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 80-100 times stronger than morphine that can be lethal in doses as small as the tip of a pencil.

From 2019-21, deaths involving fentanyl in Harris County rose from 104 to 459, a roughly 340% increase, according to the Harris County Institute of Forensic Sciences.

Hooten said illegal pill manufacturing operations are likely more widespread outside of the U.S., although he said the practice still occurs locally.

On April 19, Harris County Constable Precinct 5 deputies arrested six individuals accused of being part of a drug trafficking ring in west Harris County that officials said has been linked to several recent fentanyl overdose deaths in the Greater Houston area, according to constable’s office officials.

Multiple law enforcement agencies—including the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, the Texas Department of Public Safety and the Houston Police Department—were involved in the drug bust, which netted one kilogram of fentanyl-laced heroin, among several kilograms of other illicit drugs, officials said.

“This is real,” Hooten said. “It’s not something that [health officials are] just trying to scare people about. We see it every day on the streets, and it’s only getting worse.”

Telehealth affecting treatment

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, many health care centers were forced to shift to offering services remotely, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services officials said in a December 2021 study.

According to the study, prepandemic telehealth visits for Medicare beneficiaries went from hundreds of thousands to tens of millions with many utilizing telehealth for the first time.

Additionally, Varisco said confusion among doctors spread in the early months of the pandemic concerning what treatments were acceptable to prescribe for opioid use disorders.

A 2020 memo from Phil Wilson, the executive commissioner of the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, said buprenorphine could be prescribed virtually, but methadone required a face-to-face evaluation before the first dose could be provided. Both drugs are used to treat opioid use disorders.

“I don’t know if [the policy] was well understood by providers, and that led to lapses in our treatment,” Varisco said.

Government, local solutions

State and local entities are working to address the opioid epidemic through local funding, law enforcement resources and increased education surrounding opioid misuse.

In 2015, Texas legislators passed a law providing liability protection for doctors, pharmacists and first responders to prescribe or administer naloxone, a medicine used to rapidly reverse opioid overdoses.

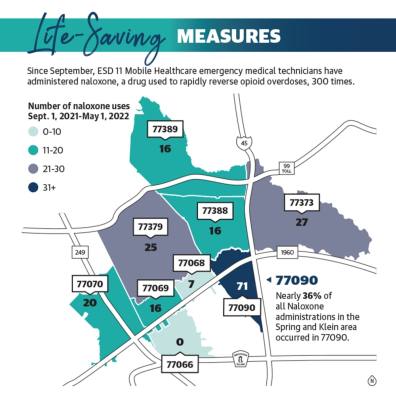

Since its inception in September 2021, Hooten said ESD 11 Mobile Healthcare emergency medical technicians have administered naloxone 300 times as of May 1—71 of which occurred in the 77090 ZIP code.

Additionally, Brown said HCPH’s Overdose Data to Action program collects overdose data to inform local prevention and response efforts. HCPH also partners with the Harris County Sheriff’s Office to identify areas of high risk and provide resources to mitigate crime and drug use.

In Texas, a slew of lawsuits filed against major pharmaceutical companies has brought in nearly $2 billion to the state with the majority of the funds directed toward opioid abatement initiatives, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton announced in a Feb. 16 news release.

Texas has secured more than $1.89 billion from lawsuits with makers and distributors of opioids, including Cardinal, McKesson, and AmerisourceBergen, to date, according to the news release. A settlement reached in October with pharmaceutical company Johnson & Johnson netted the state $290 million, including $3.9 million for Harris County.

A list of funding uses provided by the attorney general’s office includes the purchase of nalaxone or similar drugs for local EMS entities, community drug disposal programs, training for first responders, and youth-focused programs aimed at discouraging and preventing drug misuse.

Candace Runaas, director of behavioral health for Northwest Assistance Ministries, said the most important thing an individual struggling with addiction can do is ask for help. The Spring-based nonprofit’s behavioral health program assists clients dealing with mental health and substance use issues through group and community therapy, which Runaas said can be particularly beneficial follow-up care for clients after leaving a treatment center.

“It can be really helpful to have behavioral or mental health services once they return to help them manage, function and cope once they come out of treatment centers to address what’s going on with them systematically—like what are their triggers, what in their history is influencing them at this point,” she said. “By exploring that, you can help that individual recognize that they can change that pattern.”

Danica Lloyd contributed to this report.