On the heels of the busiest tropical storm season in the Gulf of Mexico’s history, Harris County is spending more on flood control along Cypress Creek than it has ever before. While the investment could reduce the likelihood of flooding for thousands of homes over the next decade, experts said flooding will remain a problem for many Spring- and Klein-area homes built in low-lying areas.

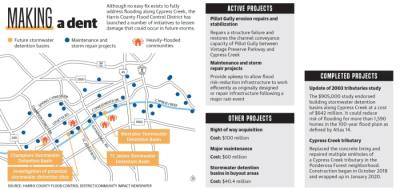

The bulk of these efforts took form after voters approved a $2.5 billion bond referendum for the Harris County Flood Control District in 2018, which put roughly $300 million toward Cypress Creek projects.

Flood-control officials said plans are coming together for more concrete efforts along the creek, and bond projects will continue through 2030. Other concepts being studied, such as a proposed underground flood tunnel, would take longer.

“I think that in Harris County, flooding will always be a risk for people in the Cypress Creek watershed and in all of our watersheds,” HCFCD Deputy Executive Director Matt Zeve said. “But we do feel very strongly that we will be lowering the risk of flooding for tens of thousands of people in the Cypress Creek watershed.”

Despite the investment, Harris County officials, local advocacy groups and scientific experts all acknowledged that due to how the area was developed over the years, flooding will never be completely solved along Cypress Creek. Meanwhile, climate change is contributing to more hurricanes and storms that produce more rain.

“Will we continue to see storms that are more intense? Yes,” said Stephanie Glenn, program director for hydrology and watersheds at the Houston Advanced Research Center. “Can we continue to plan so the impacts we see aren’t as intense? I think, as a region, we have the capability to do so.”

From passive to aggressive

More than 8,700 homes flooded along Cypress Creek during Hurricane Harvey, and another 1,700 homes did so during the Tax Day flood of 2016. Some of the more heavily affected neighborhoods in the Spring and Klein area include Ponderosa Forest, Westador, Champion Forest and Wimbledon Champions.

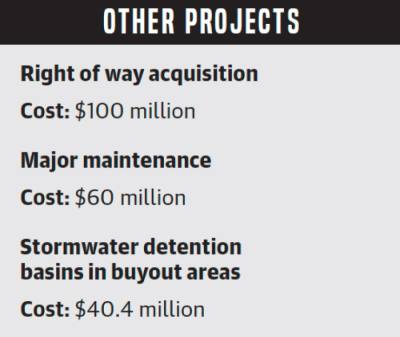

When the bond referendum was passed in 2018, the bulk of the $300 million for Cypress Creek was set aside for acquiring land, performing maintenance and building stormwater detention basins in buyout areas.

Late this summer, plans for detention basins started to emerge when district officials announced they would be taking a more aggressive approach to flood control planning.

The recent developments represent the first time there has been a specific plan for how to address flooding on Cypress Creek, Zeve said.

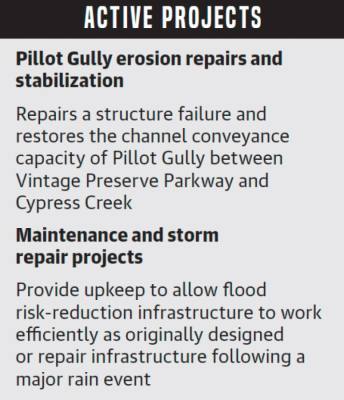

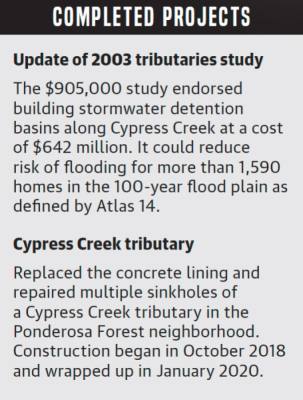

Decisions on where new detention basins will be built are being guided by a study of Cypress Creek and its tributaries that was completed in February and an ongoing follow-up study. The tributary study also called for channel improvements to parts of the creek where tributaries, such as Faulkey and Pillot gullies, connect.

One basin is proposed at Stuebner Airline Road; four are proposed between Hwy. 249 and I-45; and three are proposed downstream of I-45. However, flood control district officials said more will likely be proposed.

The district is looking to add another 25,000 acre-feet of detention along Cypress Creek. Comparatively, about 50,000 acre-feet of detention have been constructed across the county by HCFCD since it was established in 1937.

“We will very aggressively, as much as we can, pursue other funding sources, including our own capital improvement funds, to execute the plan,” Zeve said.

Local advocates, including the Cypress Creek Flood Control Coalition, said the move toward building more detention in the watershed is a step in the right direction. Dick Smith, president of the Cypress Creek Flood Control Coalition, said he was glad to see the tributaries study updated, but he was concerned about ongoing development in the northwestern part of the watershed near Waller.

The implications could mean worse flooding on Mound Creek and, by extension, Cypress Creek, Smith said. He said he believed Mound Creek was not sufficiently addressed in the study.

“Mound Creek has a potential for ... an immense amount of water coming down through it,” Smith said. “When you’re talking about Cypress Creek tributaries, that is our biggest concern.”

Likewise, Paul Eschenfelder, the founder of Cypress Creek Association—Stop the Flooding, said he believes it is possible to add 25,000 acre-feet of stormwater detention in a

highly-developed watershed like Cypress Creek, but he thinks basins that are proposed and underway need to be deepened to speed up the process.

“If you’re going to eat an elephant one bite at a time, you’ve got to take big bites and you’ve got to chew fast; otherwise, you never get done,” Eschenfelder said.

Hard rains coming

When the flood control district updated the 2003 tributaries study in February, Zeve said engineers took new rainfall data into account that was published in 2019 by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The data, referred to as Atlas 14, showed increased rainfall can be expected in future storm events in Harris County.

Under old rainfall tables, a 100-year storm in the Cypress Creek watershed was estimated to bring 12.4 inches of rain over a 24-hour period. The same storm would now be estimated to bring 16.3 inches over the same time period.

Under old rainfall tables, a 100-year storm in the Cypress Creek watershed was estimated to bring 12.4 inches of rain over a 24-hour period. The same storm would now be estimated to bring 16.3 inches over the same time period.This increase in rainfall can be tied to warmer temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico, Glenn said.

“The current predictions are more frequent and more intense storms, [which bring] more and bigger flood events,” Glenn said.

The number of storms that formed in the Atlantic Ocean during the 2020 season is indicative of what can be expected moving forward, Glenn said. Although the storms’ effects on the Houston area were minimal, a total of 31 storms formed in the Gulf since May—the most in the 170 years records have been tracked.

The future could be affected by what worldwide governments can do to form agreed-upon protocols and reduce emissions, she said.

After Harvey, the flood control district hired John Nielsen-Gammon, a climatologist and professor with Texas A&M University, to study climate change’s effects on rainfall in Harris County. The results were released in May and show a “robust upward trend in extreme precipitation ... across the southern and southeastern United States.”

“The historic upward trend is very likely to continue with global warming,” Nielsen-Gammon wrote.

The report also found an event as severe as Harvey was not likely to hit the Houston area a second time in the near future.

Finding future funding

Officials with the flood control district stressed the $2.5 billion bond is not enough to address all the needed projects in Harris County. HCFCD Executive Director Russ Poppe previously told county commissioners at least $30 billion would be needed to fully protect the county against 100-year storms.

When another bond could be called and how large it could be falls to the Harris County Commissioners Court, which would have to vote in favor of putting a bond before county voters in a future election.

Precinct 4 Commissioner Jack Cagle, who represents parts of the Spring, Klein and Cy-Fair areas, has said a second bond is inevitable. However, in a Nov. 12 interview, Cagle said it was too early to talk about a second bond.

“Before we can go to the public with a second bond, we have to be faithful stewards with the first,” he said.

One pricey concept that could play a major role in the county’s efforts on Cypress Creek is an underground flood tunnel. In 2019, the county completed a study that showed its soil is suitable for a flood tunnel, and the county is 75% of the way through a yearlong study that will determine more details about installing a tunnel, including where it might be located. Zeve said the Cypress Creek corridor is one of the routes being studied.

“The flood control district and our consultants feel like a large-diameter, deep tunnel system could be effective as a flood-damage reduction tool in the Cypress Creek watershed,” Zeve said. “So we’re moving that analysis forward, and we hope to have community engagement meetings and have a draft final report out [by] maybe February or March of next year.”

While Zeve said flood control officials are working to get through projects as quickly as they can, a number of factors require time, including obtaining federal grant money.

Dominique Tillis, whose family had to be rescued by boat during Hurricane Harvey and who has since rebuilt her Champion Forest home, said she and her neighbors still feel uneasy three years post-Harvey.

“Every time it rains, you get that lump in your throat like ‘OK, what’s going to happen this time?’” she said.