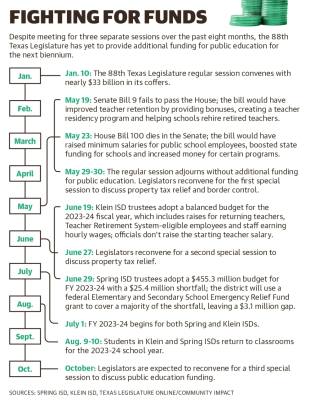

The state entered the 88th Legislature in January with nearly $33 billion in its coffers and a list of funding plans for public schools. However, beyond a few small examples, larger funding bills have yet to materialize, said Bob Popinski, senior director of policy for Raise Your Hand Texas, a nonprofit education advocacy group.

“It was a session out of balance,” Popinski said. “It was absolutely surprising. ... All the recommendations ended up failing.”

Multiple school districts across the state are either proposing or approving budget shortfalls for the 2023-24 school year. On June 17, SISD trustees approved a fiscal year budget with a $25.4 million funding gap, which will be covered by a one-time federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund grant, leaving a $3.1 million funding gap.

“Given that ESSER funding is ending, and many districts—including SISD—are still recovering from the impacts of the pandemic and grappling with soaring costs as a result of inflation, the legislators’ failure to provide additional recurring new funding was very disappointing,” SISD Chief Financial Officer Ann Westbrooks said.

Meanwhile, KlSD CFO Dan Schaefer said the district was able to pass a balanced budget for FY 2023-24 in a special-called board meeting June 19.

“Historical actions of the board and good decisions made by past leadership have helped allow us to ... weather the storm a little bit better than others,” Schaefer said. “We have a strong reserve, so we’ve been able to adopt a balanced budget this year, which, looking around, there weren’t too many of those.”

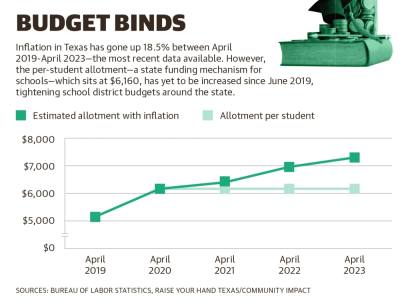

Popinski cited a number of economic factors for school districts’ budget shortfalls, such as inflation, which has driven up operating costs, as well as state and federal money tied to the pandemic drying up.

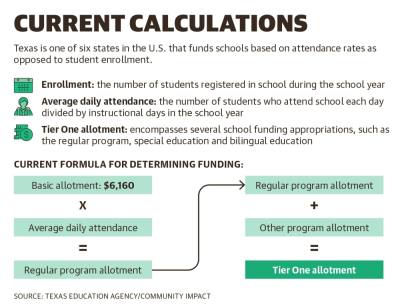

State funding for schools is determined based on a basic allotment of $6,160 per student who meets an attendance threshold. The allotment—the main income source for school districts aside from local property taxes—has not risen since House Bill 3 passed in 2019, according to the Texas Education Agency. The state would need to add roughly $1,000 to the allotment this year to match inflation that has happened since the last increase, Popinski said.

State Rep. Sam Harless, R-Spring, said he would like to see an increase in the basic allotment, but actually raising the allotment could be difficult to achieve.

“The basic allotment should be increased, but you [have] to remember that education and human health and human resources consists of 70% of the state’s budget, so it’s hard to,” Harless said.

Fighting inflation

Due to high rates of inflation in recent years for Texas—totaling about 18.5% from April 2019-April 2023, according to the Texas comptroller’s office—school districts have had trouble keeping up with rising costs of their operations.

At SISD’s June 27 board meeting, Westbrooks warned that FY 2023-24 wouldn’t be the end of budget shortfalls for the district. Without changes to the basic allotment, shortfalls can be expected for at least the next four budget cycles, with a $47.3 million shortfall anticipated for FY 2027-28.

SISD saw a 1.9% growth in its student population for the 2022-23 school year, according to a Zonda Education demographics report, but January data shows recouping pandemic enrollment losses is still projected to take at least eight school years.

Yearly budget shortfalls would eat into the district’s fund balance, which acts like a savings account for school districts and totals about $77 million, Westbrooks said. By FY 2026-27—assuming a 2% expenditure increase per year—SISD’s fund balance would be overdrawn by about $24.7 million.

While KISD was able to pass its FY 2023-24 budget without making any significant cuts, Schaefer said without an increase to the state’s basic allotment, the district’s expenses could eventually outweigh its revenue.

“Recurring revenues are not going to keep up with recurring costs, which is why, from a long-term perspective, the big push is for an increase in funding for students so that we can better match up current expenses with current revenues,” Schaefer said. “The revenue source is just stagnant right now.”

On the state side, many funding bills failed because of efforts to tie them to a private school voucher program as part of Gov. Greg Abbott’s goal to make private institutions more affordable, Popinski said. The program didn’t garner enough support in the Legislature, blocking many bills from passing that otherwise might have had the needed votes.

For example, House Bill 100, authored by Rep. Ken King, R-Canadian, would have raised the minimum salaries for public school employees; boosted the amount of money schools receive from the state; and increased funding for certain programs, such as bilingual and early education classes.

The bipartisan House proposal died during the final days of the regular session after senators added “school choice” measures, which the House historically opposed, as previously reported by Community Impact.

Retaining teachers

On the other side of the education funding issue is an ongoing national teacher shortage—nearly 11.6% of teachers left their jobs at Texas public schools ahead of the 2021-22 school year, according to the Texas Education Agency.

However, budget issues are making it more difficult to increase compensation and retain educators, Popinski said. Nearly all proposals aimed at increasing school funding in the legislative session ended up on the cutting-room floor. Among those included proposals to increase teacher pay.

Senate Bill 9, authored by Sen. Brandon Creighton, R-Conroe, was aimed at improving teacher retention by providing one-time bonuses for educators, creating a teacher residency program and helping schools rehire retired teachers. The bill failed after House lawmakers added other school funding and support measures.

SISD’s FY 2023-24 budget did not include teacher raises, and it did not raise starting teacher salaries—actions that were both taken for FY 2022-23.

“An increase in the basic allotment would have been very beneficial ... and would have provided reliable, recurring funding to provide teacher raises and address rising costs,” Westbrooks said.

Meanwhile, KISD’s FY 2023-24 budget did include a minimum pay increase of $3,600 for all returning KISD teachers as well as 2% increases and retention stipends for all other returning Teacher Retirement System-eligible employees. Market adjustments were also made to hourly wages for various support positions.

However, KISD did not increase its starting teacher salary this fiscal year as it has historically.

"We’re really focusing our efforts on experience this year,” Schaefer said. “We did a thorough review of our pay scale structure and made adjustments to experienced teachers to recognize that level of experience and make sure we’re competitive throughout the entire range.”

Hope on the horizon

Legislators will be looking at HB 100 again during a third special session in October, Harless said.

“We just have to refile [HB 100] and get it passed again, plainly without a bunch of amendments,” Harless said. “So the increased funding will be there. I think there’s going to be some teacher pay raises in there also.”

In an effort to “empower parents,” more money will be made available to school districts if the state passes the school choice legislation, said Andrew Mahaleris—a spokesperson for Abbott—in a July 6 emailed statement to Community Impact.

“Governor Abbott has prioritized public education funding and support for our hardworking teachers throughout his time in office,” Mahaleris said in the statement.

Until the special session ends, nothing is guaranteed, Popinski said.

“School districts are in a pretty tough position going forward,” he said.

Hannah Norton contributed to this report.