Understaffed by roughly 60%, the couple will need 24 employees once they open their second Spring-area snow cone store July 17; they currently employ nine.

“Worst-case scenario is going to be us spending additional hours in the shack to make it successful. I mean, we just have to risk that,” Randy Hall said. “We understand we’re going to have to work until we’re able to get to the labor force that we need. I guess the other alternative is closing—and that’s not an alternative.”

Randy Hall said it has been the worst hiring season he has ever seen as the couple competes with larger restaurants for employees after the state lifted pandemic-related business restrictions in March. Clarissa Hall said while applications usually flood in, this year they have received eight.

According to Bobby Lieb, president and CEO of the Houston Northwest Chamber of Commerce, the Halls’ dilemma reflects a widespread trend as businesses nationwide grapple with labor shortages, particularly in hourly-wage service jobs.

The Halls said they hope as pandemic fears subside and federal pandemic unemployment benefits end statewide, more workers will come their way.

However, Lieb said while he believes the demand for workers will level out, that may not happen for at least another year and a half. He does suspect labor availability will increase once schools open and parents no longer have to find day care or directly care for their children during work hours.

“Employers are still going to have to be aggressive,” Lieb said. “How they’re going to do that is like they’re doing now. They’re increasing wages. We’re seeing wage increases in your hourly wages. We’re seeing sign-on bonuses.”

Hokulia Shave Ice increased its hourly wages and gave returning workers a raise, but the Halls said offering more is difficult for a small business recovering from the pandemic.

Some larger restaurants, such as Willie’s Grill & Icehouse, however, have seen more success. Willie’s Vice President of Marketing Marty Wadsworth said the Spring location near Hwy. 249 and Cypresswood Drive needed nearly 20 additional workers when Gov. Greg Abbott announced businesses could open at 100% capacity in March.

Now, after offering a hiring bonus and updating technology to streamline service, Willie’s needs an additional six workers, Wadsworth said.

“I’ve been in the restaurant industry for 20 years, and I’ve never seen it this bad before,” he said. “Ultimately, it’s just a lot of restaurants competing for a smaller pool of potential employees. There’s an incredibly cutthroat game being played between restaurants.”

Federal benefits expire

The federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act established the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program, which temporarily expanded unemployment benefit eligibility and provided an additional $300 per week to those who qualified.

These benefits, however, ceased for Texans on June 26 at the direction of Abbott, erasing a factor many business owners and economic leaders said may have partially contributed to the widespread worker shortage.

Abbott opted out of the program in May, citing the number of well-paying jobs available statewide. The announcement came days after nearly 40 chambers of commerce and business associations across Texas signed a letter urging the state to opt out.

But Melissa Stewart, the regional executive director for the southeast region of the Texas Restaurant Association, said the TRA identified fewer than 1,100 hospitality industry workers who drew unemployment benefits in the Greater Houston area. As such, Stewart does not expect the end of extra benefits to significantly affect restaurant labor pools.

“[Restaurant workers] immediately pivoted to another job,” Stewart said.

But for Spring-area resident Rebecca Fagan, the end of unemployment benefits means her housing and health are in peril. Fagan said she previously worked as an airport security officer before her doctor told her to remain home at the beginning of the pandemic due to her health condition.

“I feel that [Abbott’s] decision was not only cruelty, [but] inhumane,” Fagan said.

With no other income, Fagan said food stamps and 40% subsidized housing are now the only government assistance she receives as she searches for another job and tries to figure out how to fund her upcoming hip surgery.

Jonathan Lewis, a senior policy analyst with Every Texan, a nonprofit that advocates to improve equity in health care, education and jobs, said it is women and people of color such as Fagan who will receive the worst effects of Abbott’s decision to cease extra unemployment benefits.

“I don’t know from day to day where this is going to take me, but all I can do is trust in our Lord and take it one day at a time,” Fagan said.

Local data and assistance

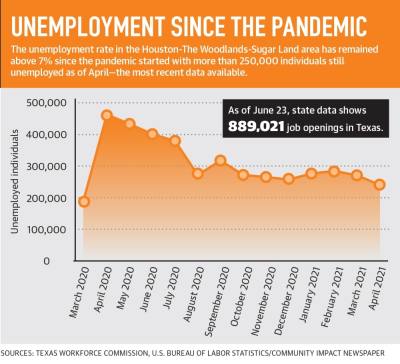

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Texas’ unemployment rate in May was 5.9%—nearly double the pre-pandemic unemployment rate of 3.1% in May 2019. Similarly, the unemployment rate in the Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land area was 6.6% in May compared to 3.4% in May 2019.

According to data provided by the Texas Workforce Commission for the Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land area, since January 2020, the leisure and hospitality industry lost two to three times more workers than any other economic sector during the pandemic. Construction and manufacturing have shown job declines since April 2020.

However, hospitality and leisure also grew more than any other economic sector with about 65,000 jobs added year over year as of May, according to TWC data. According to Lieb, physically demanding jobs, such as construction, could take the longest to reach pre-pandemic employment levels.

Between Jobs Ministry, a job support center within Northwest Bible Church in Spring, has helped 17,000 people in the Spring area and around the nation land jobs over the past 17 years. The nonprofit’s founder, Roy Farmer, said more people have been coming since April for job search assistance.

But Farmer said the nonprofit mostly helps workers find higher-skilled, higher-paying jobs by identifying strengths and networking to find the right job. Lewis said this is a goal to strive toward.

“We want people to have good jobs that allow them to afford to live ... where they want to live, health care [and] college for their kids,” Lewis said. “All these things that people just aren’t able to afford now ... because they’re in a job that’s just not a good job.”