After suffering repeated flooding along Cypress Creek, North Harris County residents and officials are pointing to historical development along the creek as a factor in recent storms that damaged thousands of homes and structures in the Cypress Creek watershed.

During Hurricane Harvey in August 2017 and the Tax Day flood in April 2016, water from Cypress Creek rose nearly 130 feet and 128 feet, respectively, and spilled over its banks—the two highest peaks in recorded history of the creek, according to data from the National Weather Service. In those storms, 8,750 and 1,735 homes in the Cypress Creek watershed were damaged, respectively.

Estimates from the Houston-Galveston Area Council show the amount of developed land within the watershed increased from about 18% in 1996 to as much as 52% in 2018.

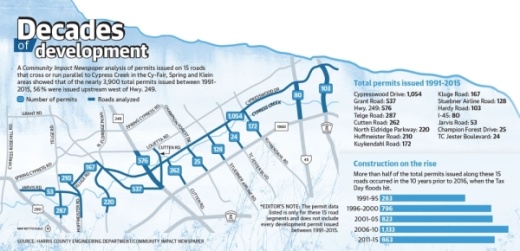

Prior to the two floods, data shows at least 3,898 development permits were issued from 1991-2015 along sections of 15 roads near the creek, some of which include Cypresswood Drive, Hwy. 249 and Grant Road among others, according to Harris County Engineering Department data.

Paul Eschenfelder, the founder of Cypress Creek Association—Stop the Flooding, an organization that educates residents about flooding, said he believes development is partially to blame.

“Too much impervious surface gives the water no place to go, no place to stand, no place to soak in,” Eschenfelder said. “For too long, in the interest of ‘economic prosperity,’ we have ignored the flood threat and implemented lax building standards, which favored the developers and builders, at the expense of the long-term occupants on those buildings.”

Meanwhile, Harris County Flood Control District officials said they believe their standards—which include criteria for building in flood plains and creating detention—have kept up to pace with development.

“I don’t think development causes the problems that ... the public thinks it does,” HCFCD Professional Engineer Gary Bezemek said. “I personally have not seen any real supportive data that shows that bayous are significantly impacted because of development, if [developers] are actually [following] the detention policy.”

Development dilemma

The first Flood Insurance Rate Map for Harris County was created in 1970 and identified the county’s flood plains—where development is prohibited—as well as the areas expected to flood in 100-year and 500-year storms, where development is allowed but with tighter restrictions, said Shawn Sturhan, the assistant manager of permits with the county engineering department.

In 1973, the minimum floor elevation for a new structure built in the 100-year flood plain was set at “base flood elevation”—the level of elevation expected to flood during a 100-year storm. By 1997, the minimum elevation in the 100-year flood plain had been increased to 18 inches. Despite several Houston-area flooding events taking place since then, development standards would remain the same until after Harvey, according to county records.

In January 2018, Harris County commissioners voted unanimously to approve the toughest standards yet for flood-prone areas. The minimum elevation was increased to 24 inches above the 500-year flood plain. In July 2019, any development in the 500-year flood plain became required to have enough detention to offset any dirt brought into the site for elevation purposes.

The 2019 standards were based on new rainfall data compiled by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that showed heavy rainfalls were more likely to occur in Harris County than previously thought, HCFCD Deputy Executive Director Matt Zeve said. Known as Atlas 14, the data showed roughly 18 inches of rainfall can be expected to fall over a 24-hour period during a 100-year event, up from the previous estimate of 13 inches.

However, any development that had been approved at the time the new regulations were adopted would be grandfathered in and would continue to be held to the former standards, officials said.

A Community Impact Newspaper analysis of permits approved on 15 roads that cross or run parallel to Cypress Creek showed that of the nearly 3,900 permits issued between 1991-2015, 56% were located upstream, or west of Hwy. 249, and 51% were issued in the 10 years prior to the 2016 Tax Day flood.

Trusting the models

As a member of the Cypress Creek Flood Control Coalition board of directors and chairman of the Cypress Creek Greenway Project, Jim Robertson works to bring attention to flooding issues, including the inadequacy of development regulations and importance of preserving green space. Robertson said his main concerns relate to a regulation that states new development cannot have an “adverse impact” on existing development up or downstream.

“A continuing question is whether or not the existing regulations achieve ‘no adverse impact,’” he said. “Two engineers can have two different interpretations; it’s not always black and white.”

According to Zeve, when a development is proposed the developer hires consulting engineers who complete hydrological and hydraulic studies and submit those results to the HCFCD. Once the HCFCD reviews the submission, the engineer revises the plans before signing off on the project.

After construction begins on the project, the engineering firm is tasked with hiring an inspector to ensure the project is built in accordance with the approved plans. Dick Smith, president of the Cypress Creek Flood Control Coalition, said he is under the impression the HCFCD does not double-check the modeling once a project is completed, essentially taking the engineers at their word.

“In the world I came out of, you have verification that the purported design is OK in the design phase, and after that you go through the as-built evaluation to confirm it met with the design,” Smith said.

Zeve said following up on every development would require a shift in how the district operates.

“That’s not impossible, but it would take some significant action by Harris County Commissioners Court and a significant money increase to hire literally hundreds and hundreds of inspectors,” he said. “The development going on in Harris County is in the billions.”

In the meantime, Smith said the coalition still has concerns about how the county tracks stormwater runoff and how it manages detention.

“The regulations for the release rate and the storage capacity were never changed up to the level that [we think] is needed—that exist today,” he said.

Cause for concern

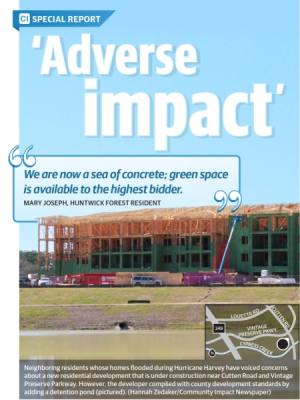

One ongoing development drawing concerns from residents is a 51-acre project located south of Vintage Preserve Parkway and west of Cutten Road. Once used as a boat launch to rescue flood victims during Hurricane Harvey, the land was clear cut in March and will soon be home to hundreds of new residents.

Under construction on the land are Mera Vintage Park, a 179-unit active-adult community developed by Sparrow Partners, and Broadstone Vintage Park, luxury apartments developed by Alliance Residential.

While engineering studies by BGE Inc., an engineer consulting firm, concluded the development will have no adverse impact to flood conditions on Cypress Creek, the development was approved before tighter development standards were enacted.

Although the land was raised 8 feet prior to construction and will include a detention pond to offset the impervious cover that will eventually cover the former green space, residents remain concerned the project will exacerbate flooding.

“We are now a sea of concrete; green space is available to the highest bidder,” said Mary Joseph, a Huntwick Forest resident who is concerned about the development’s potential to exacerbate flooding conditions downstream. “Multiunit properties are not [held] accountable for their impact to the greater community.”

While Alliance Residential did not respond to Community Impact Newspaper’s requests for comment, Luke Bourlon, a managing partner for Sparrow Partners, said Mera Vintage Park is slated to open by late 2020.

Failing to keep up

Despite changes to Harris County’s flood plain development regulations that were approved last summer, Jill Boullion, the executive director of the Bayou Land Conservancy—a nonprofit that works to preserve land in the Greater Houston area—said she feels the update is not sufficient to keep up with Harris County’s reality.

“Every time there’s a new road, a new residential development, a new commercial development—that’s roofs, that’s parking lots,” Boullion said. “And although our detention requirements have been improved and increased over the decades, I don’t know that we’ve really kept up adequately with that.”

Boullion added her hope would be that Harris County no longer allow development to occur within the 100-year flood plain.

“I think it’s more realistic now than it was three or four years ago—we have a higher sensitivity to the impact of developing that close to a stream,” she said. “We need to not put people where they shouldn’t be, and I think that’s a real issue in Cypress Creek.”

However, Zeve said he believes putting a moratorium on development is not a solution to the flooding crisis. He added that doing so would be a job for state legislators, not the HCFCD.

“Harris County is still continuing to grow. Our entire region is still continuing to grow,” Zeve said. “Redevelopment’s happening in areas that have already been developed. Our job is to make sure when those plans and those drainage studies come in, that they meet our criteria.”

State Rep. Sam Harless, R-Spring, said in the next legislative session, he is considering introducing legislation that would restrict construction of senior or assisted-living facilities within areas that have previously flooded, such as Mera Vintage Park.

“The connection between development and flooding—I think that is pretty well established,” he said. “For an area without zoning, it is challenging to keep pace with construction of roadways and development while managing the limited watershed areas without negatively impacting someone downstream.”