With a clinical background in internal, pulmonary and critical care medicine, Corry has been with BCM for 20 years. He now focuses primarily on inflammatory lung diseases, such as asthma and smoking-related chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. Most recently, Corry, along with three other BCM professors, has written and published four different articles that analyze the concept of a coronavirus vaccine and address concerns associated with the development thereof.

Corry spoke with Community Impact Newspaper on July 10 to discuss how the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic could impact the immune system as well as to share the importance of vaccine development.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In a typical, non-COVID-19 environment, how does the immune system function?

Optimal function of your immune system depends on a number of factors. If you are malnourished—obviously, not a huge problem in this country, but in pockets, it can be, and around the world, it can be a very serious problem—you could be wide open to serious, devastating infections that would be a transient, minor affair if you otherwise had good nutrition. But overall good health, meaning no major problems with any of your organs, [is also important]. So if you have major organ dysfunction, and that can literally mean any organ, that will translate into impaired immunity in some type of way. Depending on the organ and depending on the degree of malfunction, the kind of defect that you will see in terms of immune function can be minor or it can be extremely major.

Looking at this from another perspective, though, the immune system functions best in a complex—pathogen-, that is, infectious agent-filled world that we live in—it functions best when we have chronic, ongoing exposure to the different bugs that are in our environment. By having those normal bugs including bacteria in our guts and mouths and all over our skin, fungi and many other viruses—that does help very, very much to condition our immune systems and helps to keep it on high alert so that we're much better able to survive serious infections when they come our way.

In a COVID-19 environment, how is immune system performance affected?

Technically, it's not possible to answer that question because it's really not been studied, and we're too new to the COVID-19 business, but I think it's possible to make some reasonable speculations. The kind of social distancing that most of us are conducting and the isolation that we are involved in is probably not going to translate into any kind of serious immunocompromise. We still have bacteria in our guts; we still have lots of viruses coursing through our blood, as well as fungi and parasites—we have all of these still, and isolation doesn't really change that.

What some people might try to argue is that by having more social contact, we would be exchanging more viruses, and they could theoretically argue that maybe we would be better prepared to handle COVID-19. But in reality, that's probably not the case. The majority of viruses that we exchange are rhinoviruses, which are totally different from coronavirus. You can have all of the rhinovirus infections that you want, but that's not going to protect you from coronavirus. There are other coronaviruses that do cause things like colds—they're not the COVID-19 coronavirus, but they're closely related—but you could make the argument that maybe, exposure to them might confer a cross-protective immunity to the COVID-19 virus. There is some merit to that. There is evidence that exposure to SARS 1 does confer cross-protective immunity against SARS 2. So that's the one thing we could be missing out on, but I'm guessing that will turn out to be a very minor issue in the long run.

Are you concerned people's immune systems will be more susceptible to illness post-COVID-19?

Let's say a vaccine comes out in the next year, and it gets widely deployed, and we achieve herd immunity within the next one to two years. I think this issue is probably going to be moot. As we emerge suddenly from our isolated state, we're not going to be highly susceptible suddenly to all kinds of infections, and the reason for that is because our immune systems are so effective because they have this amazing property of memory. So our immune systems remember for years or decades, depending on the exposure or the pathogen, that we have had that prior infection, so when you next get that infection, [the immune system] can mobilize forces very, very rapidly and stomp it out before it becomes a problem. So we can retain that immunity over one to two years, for sure, for the vast majority of things. But if this were to go on for, like, decades and we suddenly emerged from strong isolated conditions over a period of decades, then that could be a problem. But nobody's looking to be tied down for that kind of time frame. We're looking at about one to two years.

What can people do to keep their immune systems functioning properly during this time?

It's particularly important during any pandemic—and of course, no one alive today, with a few exceptions, has lived through anything like this; the last [pandemic] was in 1918. So we're not really used to thinking along these lines, but it's absolutely essential that we take stock of our personal habits and our overall health. The best way to keep your immune system healthy is to make sure that all your organs are healthy and that you have excellent nutrition. So if you have chronic organ insufficiency—so, for example, maybe you have smoking-related emphysema or alcohol-related cirrhosis, or maybe you're overweight, which can cause mild to very severe levels of organ dysfunction. ... The very strong recommendations to do what you can to improve your health overall is improving your organ function. If you're smoking, it's really essential [now], more than any other time, to stop smoking. If you're drinking too much alcohol, knock it off. If you are massively obese, this is a great time to think about trying to get some of the weight off. All of this will improve organ function and improve your ability to survive this really terrible infection.

When a new virus like COVID-19 presents itself, what immunity (if any) does a population have to it?

Just the fact that we have this pandemic means that we, as a population, don't have much immunity against this virus. There's other coronaviruses out there that have been infecting humans forever, ... but that does not confer cross-protective immunity because if it did, we probably would not have a pandemic, and we do. So what can we do to confer specific immunity to COVID-19? There's really only one answer to that, and that's a vaccine. Many groups are working on [developing a vaccine]; clinical trials are starting; we've recently published four papers on this. But the overall gist is that we already have very good vaccines against this COVID-19 virus. We have to make certain that they are safe for humans, and they don't cause side effects and all the evidence [shows] that we will not see the kind of side effects that a lot of people are worried about, so once it's widely deployed and we get a lot of people vaccinated, that's the quickest and best way to achieve herd immunity. There's no other way to do this.

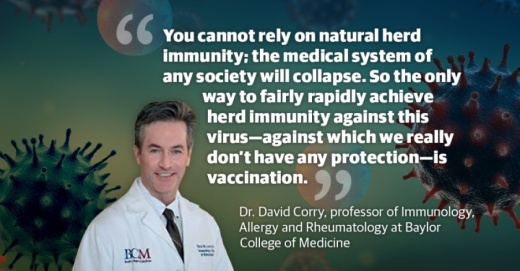

Sweden is one country that's [telling people], "Don't hibernate. Don't social distance," and [following this idea of], "Let the virus work its way through the community. It'll spread like wildfire; some people will die, but we'll have herd immunity fairly quickly, and that's the best way to protect future generations." That model is playing out right now in Sweden, and they're having some second thoughts about that, but we've already seen in the U.S.: That approach is not going to work. The reason why is too many people are going to get sick; they're going to have to go into the intensive care units and clog up our hospitals, and our hospitals are going to basically collapse. We're not going to be able to take in anybody else with any other kind of condition. You cannot rely on natural herd immunity; the medical system of any society will collapse. So the only way to fairly rapidly achieve herd immunity against this virus—against which we really don't have any protection—is vaccination.

How will the anti-vaccine movement impact COVID-19?

There's a very strong anti-vaccine movement in this country. ... So many people are jumping on this anti-vaccination bandwagon ... and [ascribing] to that flawed way of thinking that they won't get vaccinated. In a worst-case scenario, we will just never achieve herd immunity [to COVID-19]. But it's not just COVID-19. Many, many pandemics will come. We can't prevent pandemics; they will continue to happen. You have to vaccinate. That is the only strategy. But if you have a population that's skeptical—that won't vaccinate—then you will never achieve that herd immunity. You will never get the virus under control. And you so will have a continual, low-grade crisis happening, and you'll never protect future generations. They will always be susceptible to these life-threatening infections.

As a society, we have to come together and banish this notion that somehow, vaccines are bad. We're hoping that maybe, the best way of dealing with this is just to strengthen already existing laws, and our laws are already quite strong about vaccination, but there is wiggle room to make them even stronger, so, maybe stronger legislation mandating vaccination and even removing religious exemptions. It sounds anti-liberty, which, for many Americans, is a very tough pill to swallow, so we'll leave the decision-making to the politicians. But I think certainly I and many other physicians who are interested in public health—we are very much on the side that this is a good way to go: to strengthen existing laws, particularly given the serious nature of the anti-vaxx movement, which is very hard to counter through other means.

How far away do you think the medical field is from developing and distributing a vaccine for COVID-19?

Dr. Anthony Fauci says 12-18 months, and I think that's still a reasonable timeline. Things are moving actually quite fast and in the right direction, and so I do have optimism after reviewing literature and writing fairly extensively in this area. We already have a vaccine; we just need to show that it's safe. And then, after that's done, we need to ramp up manufacturing and make hundreds of millions of doses available to not just Americans, but also around the world. This is a worldwide pandemic. So that will take time to ramp up, and distribution of an effective vaccine won't happen around the world uniformly. But certainly, we hope that it will happen fairly quickly in the United States, where much of the vaccine work is being done.