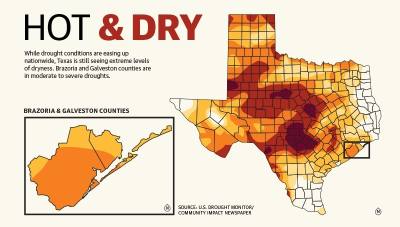

Due to a lack of rain and persistently high temperatures, parts of Brazoria and Galveston counties have been in a D3, or extreme, drought since mid-June, according to standards set by the U.S. Drought Monitor, run by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and other groups. This is affecting everyone from residents to cities, some of which had to enact drought contingency plans to conserve water.

“This drought is extreme,” said Jimmy Fowler, meteorologist for the National Weather Service’s Houston/Galveston office. “It’s pretty dry.”

While recent rains in August have brought relief, they could bring another problem, such as floods, which tend to be worse after a drought, said John Nielsen-Gammon, Texas state climatologist with Texas A&M University.

Other concerns include droughts Other concerns include droughts and high temperatures becoming more common.

“Climate change may be making the difference between 101 and 103 [degrees] on a particular day,” Nielsen-Gammon said.

Double whammy

Brazoria and Galveston counties entered severe drought—the third highest of the Drought Monitor’s five drought tiers—on April 5. By June 14, the counties had entered the second-highest tier, extreme drought, Fowler said.

While some areas of the state are seeing exceptional drought—the most intense level—that tier has not been reached in Brazoria or Galveston counties. Most of the counties were in severe drought as of Sept. 1, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Contributing to drought are the weather patterns seen in the Pacific Ocean, Fowler said.

When the ocean’s surface water temperatures are warmer, it is considered in El Niño, and Texas is more likely to get rain. When the waters are cool, it is considered in La Niña, resulting in drier conditions.

The ocean has been in La Niña for three years, Fowler said.

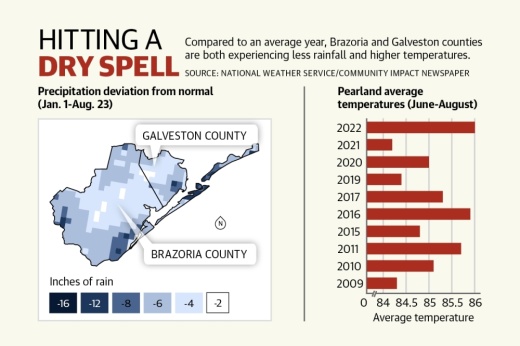

As of Aug. 23, Brazoria and Galveston counties had seen 4-12 fewer inches of rain than normal since Jan. 1. Only small pockets saw average amounts of rainfall, according to NWS maps.

On top of that, the Greater Houston area is experiencing one of its hottest summers on record. Hot weather evaporates what little moisture is present quicker, Fowler said.

June through August was the hottest three-month period for Pearland since at least 1997, beating out 2011, the last major drought year on record, at an average of 85.7 degrees, according to National Weather Service data.

In Galveston, June through August has been the hottest since 1874 at an average of 88 degrees. Ranking second is June through August 2011 at 87.3 degrees.

“Just the fact that it’s been so warm has really fast-forwarded the drought process,” Fowler said.

Contingency plans

Some cities responded to the dry conditions and high temperatures by activating their state-mandated drought contingency plans, which aim to conserve water during droughts and other emergencies.

Pearland entered Stage 1 of its four-stage plan July 21. The plan was activated due to the city having at least 60% of its water capacity used each day in a three-day span, Water Production Superintendent Julian Kelly said.

“We usually look at weekly productions and see if we are eclipsing our production numbers,” he said.

Stage 1 calls for residents to voluntarily reduce water consumption, and that reduction in use mixed with some rainfall allowed the city to lift restrictions Aug. 12.

“I think we saw a good reaction from our citizens with the voluntary restrictions,” Deputy City Manager Trent Epperson said.

Manvel also enacted its drought contingency plan this summer.

“Manvel has, fortunately, received intermittent rainfall since the drought contingency plan Stage 1 was issued that [has] limited current drought measures, and because of this, the city has not had any severe drought-related impacts,” the city said in an Aug. 15 written statement.

Meanwhile, some cities, such as League City and Friendswood, never had to activate their plans.

One factor that can contribute to whether a city activates its drought contingency plan is ground cracking. The more extreme a drought, the more earth retracts and shifts, which can break water mains, leading to reduced water capacities and the activation of drought contingency plans, according to city officials.

“We’ve seen an uptick in main breaks,” Epperson said of Pearland. “We jump on those as quickly as possible.”

Ending the drought

In August, the southeast Houston area started seeing more rain, which began to push the area out of drought. As of Sept. 1, drought levels in Brazoria and Galveston counties were moderate to severe.

For the rest of 2022, the outlook calls for abnormally high temperatures and dryness to continue, Nielsen-Gammon said. September and October tend to be wetter months, historically, which could bring more relief, though he said the odds favor dry conditions. A tropical storm would also bring rain, he said.

“But that’s a dangerous way of ending drought,” he said.

It is possible that a single heavy rainfall could bring the area out of a drought, but that much rain all at once would likely result in other problems, such as flooding. The ideal way to get out of a drought is multiple weeks of above-average rainfall to not only meet norms, but also exceed them to make up for the months of lackluster precipitation, Fowler said.

Matthew Perry, assistant district manager with Houston-based arborist company Davey Tree, agreed. When soil is dry, it can handle only so much water at once, and the rest is not soaked into the ground and instead runs off into streets, he said.

“What you need instead of heavy downpours ... is really just a drizzle,” he said. “A slow soaking of the land.”

All told, the drought of 2022 has not been as bad as the drought of 2011, which is the benchmark by which other droughts are measured, Fowler said. In 2011, Brazoria and Galveston counties entered extreme drought May 17 and stayed there until Dec. 27.

“It was not only a very long drought duration, but it was also very wide,” Fowler said, noting on Oct. 4, 2011, 88% of Texas was in extreme drought.

Future concerns

Some officials have concerns about the future tendency for hot and dry conditions.

Looking at precipitation trends over the past few decades, it is difficult to get a feel for the future. It seems as though Texas is going toward the extreme on both ends: periods of extreme drought and separate stretches of extreme precipitation, Fowler said.

From a temperature standpoint, meteorologists have seen a consistent increase over the past few decades, particularly in overnight temperatures. It no longer gets nearly as cool overnight as it used to, which affects how quickly droughts taper off, Fowler said.

Due to regional population growth, climate predictions and rain variability, the future drought in Texas may actually be a megadrought, which lasts at least two decades, Nielsen-Gammon said.

Megadrought is caused by natural climate cycles and human-induced climate change, which climatologists such as Nielsen-Gammon said will cause higher average temperatures that increase evaporation rates and affect the intensity of rainfall.

“Texas isn’t in a megadrought right now, but one is always possible,” he said.

Rainfall variability also plays a role in determining the likelihood of megadrought. Texas has historically had unpredictable rainfall patterns, making it difficult to predict drought, Nielsen-Gammon said.

“Texas is quite variable from ... year to year,” he said. “We’ve had some decades with 50% more rainfall than other decades, for example.”

Shawn Arrajj and Grace Dickens contributed to this report.