While the protests are dying down, work is still being done in Pearland and Friendswood to make sure these types of offenses do not happen locally.

The Brazoria County chapter of the NAACP held a town hall in June to discuss changes that need to be made and how the community can come together. The event featured speakers from several municipalities and police departments in the county. The organization also hosted a prayer service in Pearland shortly after Floyd’s death.

“Prayer resolves every situation. We wanted to bring our community together to assure that in our county and our community, people want to sit at the table and have those conversations,” said Eugene Howard, the president of the Brazoria County chapter of the NAACP.

Racial tensions

Racism is an issue people think happens outside of Friendswood, not within it, said Gabi Rodriguez, a former Friendswood resident and a University of Houston student. Rodriguez was one of the organizers of the protest in Friendswood in early June.

“A lot of people in Friendswood think of systemic racism as something that exists outside of this community, but that here in Friendswood, it doesn’t happen,” Rodriguez said. “Because this is a really white community, there are a lot of people that have never met a Black person; there aren’t really any at school.”

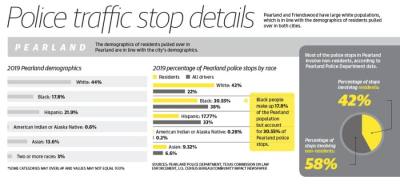

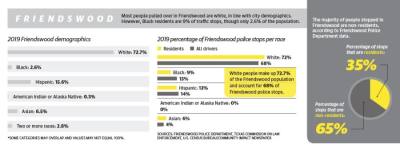

According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Friendswood’s population was 72.7% white in 2019, and Pearland’s population was 44% white. By contrast, Pearland’s population is 17.8% Black, and Friendswood’s is 2.6% Black.

The Pearland Police Department posted information about its procedures on its website to be transparent about what is and is not allowed.

In Pearland, the use of deadly force is allowed, but only when an officer’s life is at stake, according to the department’s use-of-force policy. An update on its use of force policy is in the works, Spires said in a written statement. Friendswood’s Police Department declined to comment on its use of force policy.

Pearland Police Chief John Spires released a statement from the department after Floyd’s death detailing a lesson he learned early in his career: When one officer messes up, all are held accountable, he said.

“As peace officers, our power and authority are granted from the public. When that authority is abused, the public not only has the right but the obligation to hold us accountable,” he said in a statement.

Police throughout the state, including in Brazoria County, must be trained on proper de-escalation tactics, which requires force be used only as a last resort, Brazoria County Sheriff Charles Wagner said.

“You want to use as minimal force as possible. I found out a long time ago, personally, I can talk a lot more people into jail than fight them into jail,” Wagner said.

Police officers are lucky to have a good relationship with residents in the county, Wagner said.

“The ideal is that we should a part of the community. We need to cooperate and get along with each other,” he said.

A lot of civilians do not know what cops go through, Galveston County Sheriff Henry Trochesset said.

“The majority of peace officers are good people,” he said.

Change requires buy-in

Making changes toward equality requires acknowledging inequality exists, even in Brazoria and Galveston counties, said Felicha Jones, the founder and owner of the Smart Scholars Foundation.

Jones is also a member of the Brazoria County chapter of the NAACP and was one of the moderators of the town hall the organization led.

Jones is also a member of the Brazoria County chapter of the NAACP and was one of the moderators of the town hall the organization led.“Being that I was raised in Brazoria County, I saw a lot of the prejudice going on even then and back in the day. Personally speaking, it has worsened over the years,” she said. “We have to be honest with ourselves and each other that the problem does exist in Brazoria County.”

Jones, like Howard, said she believes change is going to take buy-in from many aspects of the community. After Floyd’s death, Jones began to see that.

“Prior to [Floyd’s death], I think it was swept under the carpet. Quite naturally, it has resurfaced to the forefront, causing us to look at the situation and admitting that there is a problem and it is time to fix it,” she said.

More people of color are pulled over by Pearland police than white people, according to data from the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement. However, most of the people pulled over in Pearland are not residents, Spires said.

In Pearland in 2019, 38% of the people stopped by Pearland police officers were Black, while 22% were white. Out of Pearland residents pulled over in 2019, 42% were white and 30.55% were Black, which is closer to Pearland’s demographics, Spires said.

The Pearland Police Department started using a data-driven approach to focus efforts in areas with a lot of crime in 2016, Spires said. The department pulls over most people at the Hwy. 288 and Broadway Street intersection, where 10.8% of the crashes in the city occur, Spires said. The retail in the area brings a lot of non-residents, he said.

In Friendswood, the majority of the people stopped were white. However, traffic stops do not necessarily paint a complete picture, Friendswood officer Lisa Price said in an email.

“Census data, when used as a baseline of comparison, presents the challenge that it captures information related to city residents only,” Price said. “Thus, excluding individuals who may have come in contact with the Friendswood Police Department but live outside the city limits.”

Howard has asked for better transparency and implicit bias training in police departments. He is hopeful for change as he has seen the community respond, he said.

“If we are to be equal, we can’t beat our citizens in the street,” he said. “The ruthlessness, the arrogance of what the officers did [to Floyd] was undeniable... It shook the American conscience.”

Both Howard and Jones see a lot of changes coming from future generations. Jones’ nonprofit, the Smart Scholars Foundation, works with local youth. The Smart Scholars Foundation held another town hall June 30, allowing children to pose their own questions to Houston-area leaders.

“[Adults] have to be very careful how we handle this,” Jones said. “If we are out fighting and destroying property, our kids are under that influence. But on the flip side, if they see us standing united as a nation and saying we will not be divided by this anymore, they will mimic that.”

If any change will come, it will require support from the public, police and elected officials, Jones said.

“It took the world to rise up with us. We didn’t rise up by ourselves this time. We had whites; we had Asians; we had Hispanics. We had every nation rise up with us this time and agree that enough is enough,” Jones said. “That within itself brought about the change, and that is what it is going to take. We need to pause a moment and look at that. We all finally came together.”