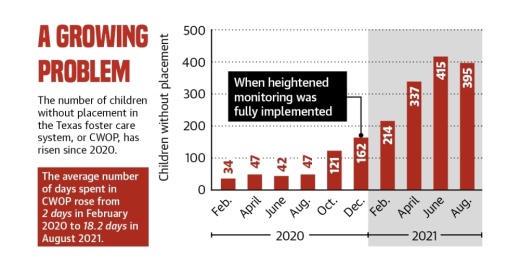

According to DFPS officials, individuals in the state’s foster care system receive a “child without placement” designation, or CWOP, when the state cannot find a suitable and safe placement for that child, requiring the DFPS to provide temporary emergency care until a placement can be secured.

Over the last two years, the state has increasingly relied on unlicensed placements—often motels or office buildings—overseen by caseworkers. In October 2019, 32 children were in such placements statewide, according to DFPS data. By August 2021, the most recent data available, that number had risen to 395 children.

Many of these children requiring placements have experienced physical and sexual abuse and neglect, and that abuse is increasing in frequency and intensity, according to Kristi Hawkins, executive director of Brazoria County Alliance for Children.

“We have seen a huge increase,” she said. “We are seeing more severe physical abuse.”

Meanwhile, COVID-19 has caused a decrease in the number of foster families available to foster children, said Charity Eames, the chair of the Children’s Services Board of Galveston County and clinical director of DePelchin Children’s Center in Houston. The board provides oversight of county funds for foster children, and the children’s center provides children’s mental health, intervention and welfare services.

Foster families have not been immune to the financial hardships and illness brought on by the pandemic. This has caused many foster families to give up fostering, at least temporarily, Eames said.

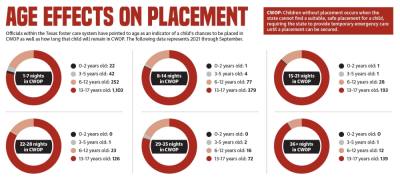

Most children designated as CWOP are older, and many of them have been in legal trouble, Eames said. Some are more content sitting in a CPS office or getting placed in a hotel than being placed with a foster family, Eames said.

Eames said some of her fellow board members work with foster children and say that sometimes it is the children themselves who choose to be without placement. For instance, some CWOP are put into foster homes, and they repeatedly run away, Eames said.

“Unfortunately, sometimes the kids don’t want to be placed, so they cause trouble in the placements that are found for them,” she said. “These are not the easiest kids to place.”

Extenuating circumstances

In an August CWOP report, DFPS officials said the number of children designated as CWOP had risen, in part, because of heightened monitoring regulations mandated after U.S. District Judge Janis Graham Jack ruled in 2015 that foster children in Texas “almost uniformly leave state custody more damaged than when they entered.” Resulting system reforms included heightened monitoring, which is implemented when certain foster care system entities have had a high rate of violations.

Entities placed under heightened monitoring are given a plan by court monitors to address deficiencies and, failing that, face consequences, such as having their licenses revoked.

Since January 2020, 21 general residential operations—facilities with 13 or more children—have been shut down or had their licenses revoked statewide, leading to the loss of about 1,200 beds, according to a September court update. Rebecca Mercer, regional director of statewide adoption agency Lonestar Social Services, said heightened monitoring has also led to some foster parents removing themselves from the system altogether. She also said the pandemic has made finding placements more difficult.

“We’ve had a lot of foster parents that will come to us and say, ‘Until COVID is over, we’re not interested in taking placements anymore because it’s just too much,’” she said.

Arrow Child & Family Ministries, a Houston-area Christian nonprofit organization, is a partner agency that provides child welfare services to children and families throughout Region 6—which includes Pearland and Friendswood.

Officials at Arrow said the area has followed state trends; plus, CPS is no longer licensing adoptive families in Region 6, leaving the burden of licensing, hosting informational meetings and training prospective parents on local agencies such as Arrow.

Searching for solutions

The DFPS has identified a need for 669 additional beds throughout the state to meet growing demands on the welfare system. Additionally, the department said it is lacking an adequate number of CPS caseworkers with 236 vacancies statewide.

With these issues, Texas passed several pieces of legislation during the pandemic to address the needs.

State Senate Bill 1896, passed in May, revised and added regulations for the DFPS, including forbidding it from housing a child in an office overnight, expanding eligibility for therapeutic foster care and transitioning into electronic case management.

Additionally, the DFPS requested an additional $83.1 million as part of Senate Bill 1 to hire 312 caseworkers, which the Legislature fully funded, according to the September CWOP report. House Bill 5, which passed in September, allotted an additional $90 million to the DFPS, which will be used to retain providers and increase capacity to serve foster youth.

“The importance of this funding cannot be overstated,” said Melissa Lanford, the media specialist for DFPS Region 6. “It is the difference between a real placement for these older children and continuing to live in a CPS office or hotel.”

In the September CWOP report, DFPS Commissioner Jaime Masters said many providers have cited heightened monitoring as a reason for declining a placement, although she noted that did not indicate the department’s disapproval of the mandate.

“DFPS is not ‘blaming’ the [CWOP] crisis on the court’s heightened monitoring orders,” Masters said. “While the monitors have noted DFPS’ ‘collaborative’ efforts of listening to concerns of its stakeholders, it is an undisputed fact that DFPS cannot do this alone.”

She said caseworker turnover resulting from overworked employees has contributed to the growing number of CWOP. Between February and July, the DFPS hired 319 caseworkers, but 309 caseworkers left their roles during that time. Exit surveys in 2021 said 86% cited work-related stress as a cause for ending their employment, up from 40% in 2020.

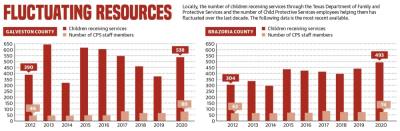

In Brazoria County, the number of children receiving DFPS services increased from 440 to 493 from 2019 to 2020. The number of CPS workers stayed flat, moving from 73 to 74.

“With the growth in the county, they’re just not able to keep up with the need and the demand, unfortunately,” Hawkins said.

In Galveston County, the number of children receiving services increased from 376 to 538 from 2019 to 2020, and the number of CPS workers moved from 67 to 80. Data for 2021 is not yet available.

On Jan. 10, a panel appointed by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott described Texas’ foster care system as “woefully inadequate” and recommends increasing mental health resources, improving guidelines and infrastructure, and eliminating barriers to services.

“[The recommendations] will impact everything we do,” said Debi Tengler, Arrow’s chief relations officer. “These kids are our future, and we would love for people to give us a call and consider not only helping [CWOP], but all children in foster care.”

Laura Aebi and Danica Lloyd contributed to this report.