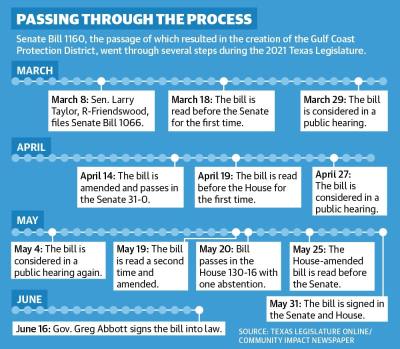

State legislators approved and signed the bill in the Texas Senate and House at the end of the legislative session in May. Gov. Greg Abbott signed it June 16.

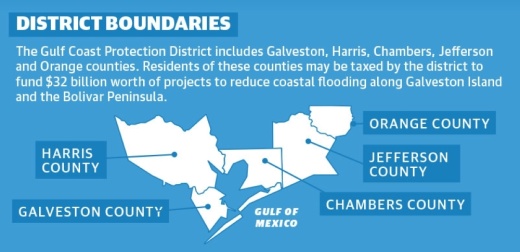

While some have expressed worry the district will result in more taxation to fund the planned $26 billion coastal barrier and related projects along Galveston Island and the Bolivar Peninsula, officials said there are other funding avenues.

State Rep. Dennis Paul, R-Houston, filed House Bill 3029, identical to SB 1160 filed by Sen. Larry Taylor, R-Friendswood, in March. According to Paul, the protection district was created to receive and manage funds for projects related to storm protection in areas around the Texas Gulf Coast.

Bob Mitchell, president of the Bay Area Houston Economic Partnership, said the barrier would not only protect residents but spur progress.

“We get this thing built, it’s going to up economic development even further,” he said.

An 11-member board will oversee the district with one representative appointed by each of the five counties and six appointed directly by the governor, Paul said. Mitchell has been appointed to the board.

This board will have the authority to issue bonds, collect fees and impose a tax on district residents to go toward projects related to the coastal barrier. Paul said this tax rate would likely depend on the amount of federal funding received.

Paul also said the board’s taxing ability is one of the most restricted in the state.

“The board would say that they want to have a tax, but it would have to be voted on by the entire citizenry of the district,” he said. “So they can’t ever have any tax without the citizens saying, ‘Yes, we want to have the tax.’”

If a property tax is created, Paul said there would be a cap of $0.05 per $100 valuation, a limit that only the state Legislature could change in the future.

Mitchell said a tax likely would be only half of the cap, or $0.025 per $100 valuation. Such a tax would equal $75 annually on a $300,000 home, which is far cheaper than annual flood insurance. Furthermore, creating the barrier may result in lower flood insurance rates for residents, leading to a long-term net gain for taxpayers.

“It more than pays for itself,” Mitchell said.

However, a tax might not even be necessary, Paul and Mitchell said. Instead, officials might opt to fund the project with resilience bonds, which is a way in which companies would reimburse the barrier’s cost.

Large companies along the coast, such as chemical and energy plants, pay significant amounts in flood insurance annually. Theoretically, these companies could use the money saved on insurance from the coastal barrier to pay for the barrier. Using resilience bonds, as they are called, makes a lot of sense, though Mitchell said many details have yet to be worked out to determine if it is viable.

“The idea is if you can prove to [companies] this barrier will protect their assets, ... they will begin saving money on ... insurance,” Mitchell said. “At some point, the bonds are paid off, and they’re home free.”

A report from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers regarding the coastal barrier is expected to go in front of U.S. Congress this August, when the federal government will decide whether to fund the project, Paul said.