Consulting firm Freese and Nichols came up with the proposed projects after a year of research of the Clear Creek and Dickinson Bayou watersheds.

As communities fund local drainage projects—such as those being covered by League City’s $73 million drainage bond—and potentially part of the $32 billion coastal barrier posed for construction near Galveston, local municipalities will have to consider how to afford the massive costs of regional flooding fixes.

“We always knew this was going to be a lot of hard work followed by another order of magnitude of harder work,” said Chuck Wolf, an associate with Freese and Nichols. “The funding side of this is a big challenge.”

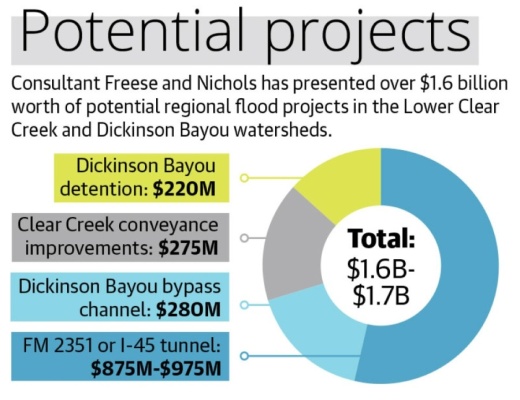

Proposed projects

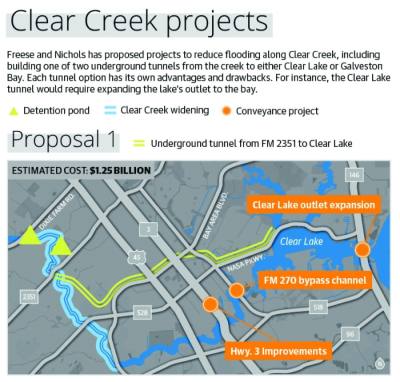

On March 31, Freese and Nichols presented regional drainage projects for Clear Creek, which runs through Friendswood and League City. Proposed solutions for the area relate to conveyance, or the act of moving water, and detention, the act of holding excess water in place, totaling $275 million.

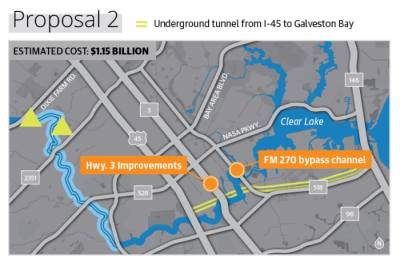

Adding $875 million to $975 million to the cost is the proposal to build one of two underground tunnels. One would run from FM 2351 to Clear Lake, and the other would run from I-45 to Galveston Bay.

Over a 50-year period, the conveyance, detention and one of the two tunnel projects would save an estimated 2,298 to 3,109 structures from flooding and prevent $71 million to $95 million in damages, said Brian Gettinger, Freese and Nichols project manager.

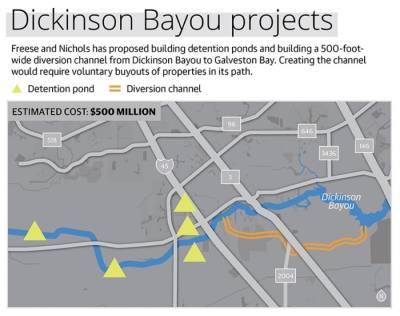

Along Dickinson Bayou, the proposed projects are not as costly.

Similar to Clear Creek, Freese and Nichols proposed building detention ponds along Dickinson Bayou, but the biggest component is a 500-foot-wide channel that would divert water from Dickinson Bayou east of I-45 to Dickinson Bay. The estimated cost is $500 million.

Over 50 years, these solutions would save 15,000 structures from flooding and prevent $245 million in damages, Gettinger said.

“A huge number of structures are removed from the flooding risk,” he said.

For both sets of projects, buyouts of properties either prone to flooding or in the way of certain projects, such as the bypass channel, would likely be required, Gettinger said.

For both watersheds, projects cannot worsen flooding downstream. The same parameter exists for the $295 million federal project along the upstream portion of Clear Creek that separates Harris and Brazoria counties, officials said.

Funding questions

Facing over $1.6 billion in potential costs, officials who initiated the study said they were not surprised by the high price tags.

“When we first started on this project, we actually tried really hard to do this without tunnels in the Clear Creek area,” said Wolf, who noted Clear Creek’s mostly developed land does not allow for inexpensive solutions. “I wasn’t surprised at the cost. That doesn’t mean that I’m not concerned about it.”

League City City Manager John Baumgartner agreed.

“I think we knew the tunnel solution was in the billion-dollar range,” he said. “If we can do something to arrest the potential for flooding in the region, ... hopefully we will see some savings on the insurance side.”

Friendswood City Council member Steve Rockey, who served on a subcommittee to mitigate local flooding after Hurricane Harvey, said tunnels could make a major difference for the area. For instance, the FM 2351 tunnel would have saved hundreds of homes from flooding during Hurricane Harvey, Rockey said.

That said, Rockey acknowledged such a costly project is a hard sell.

“Digging tunnels is expensive,” Rockey said. “I’m not holding my breath on the tunnels, to be honest.”

Longtime Friendswood resident Philip Ratisseau, whose home flooded with 3 feet of water during Harvey, agreed.

“Nobody’s going to give us a billion dollars to do [tunneling],” he said. “We know that.”

Rockey said while certain proposed projects from the study may not happen, there are some cities could find funding for, such as the detention ponds, he said.

“But obviously, League City and Friendswood, who are the primary beneficiaries, would have to get federal funding,” he said.

Friendswood city officials declined to comment, pending a formal presentation on the projects from Freese and Nichols.

Gettinger said there are several potential funding partners. State offices such as the Texas General Land Office to federal groups such as the Army Corps of Engineers may be willing to help fund projects with a local match, but funding partners come with their own challenges, such as ensuring projects attain certain cost-benefit ratios, Gettinger said.

Local dollars

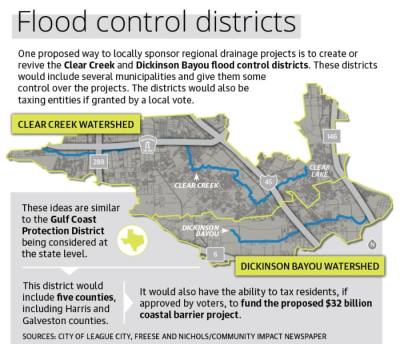

A local funding option would be to create a Dickinson Bayou flood control district or revive the one that once existed in the Clear Creek watershed.

The Clear Creek Flood Control District, which covered area counties including Harris and Galveston, was created by the Texas Legislature in the mid-1990s to fund regional drainage projects. A vote by residents to grant taxing authority to the district failed in the late ‘90s, so the district was never fully established, and it would take legislative approval to revive it, officials said.

In a similar but unrelated vein, such a district made up of Galveston, Harris and other counties is being considered at the state level to help fund the coastal barrier to protect the Greater Houston area from storm surge flooding, said Sen. Larry Taylor, R-Friendswood. Meanwhile, the regional projects Freese and Nichols have proposed would alleviate riverine flooding—a separate issue.

House Bill 3029, which would create the district, has not been finalized, but it is probable the district would need to tax residents at least $0.025 per $100 valuation to afford the maintenance the project would require.

“That’s a very small price to pay for the huge amount of protection we’d be getting,” Taylor said.

Meanwhile, Baumgartner said regional flood control districts could cost as much as $0.25 per $100 valuation, or $600 to $800 annually for the average homeowner.

“Frankly, very few people support another taxing entity. That idea has been turned down by the citizens before,” Ratisseau said, adding it is not “practical” to create a local taxing district when one is being considered for the coastal barrier.

Rockey said he would expect many residents whose homes did not flood during Harvey to balk at the idea of increasing their taxes for major drainage projects. Then again, even when residents’ homes do not flood during storms, they are affected economically by living in cities that experience flood damage, Rockey said.

“Everybody has to make those decisions on taxes, including me,” he said.

Galveston County Precinct 4 Commissioner Ken Clark, who represents parts of Friendswood and League City, said residents will have to decide the importance of flood control.

“People don’t want to flood, and, unfortunately, somebody’s got to pay for these projects,” he said. “Are we really interested in flood control, or are we just giving it lip service?”

Freese and Nichols officials said they have seen cities pull off massive, expensive regional projects before.

“If you have the community support and the political support ... large projects like this can happen,” said Jim Keith, technical lead with Freese and Nichols. “It’s ... big costs, but that doesn’t mean it’s impossible.”

The Freese and Nichols team is going to take feedback it receives about the proposed projects, process it and come back with final recommendations around late May. Those ideas will be pushed out the public, and, ultimately, cities will work to build consensus on what should be done to address flooding, Baumgartner said.

“It’s all for naught if we can’t ... make all our communities more resilient to the flooding,” he said. “I welcome the challenge.”