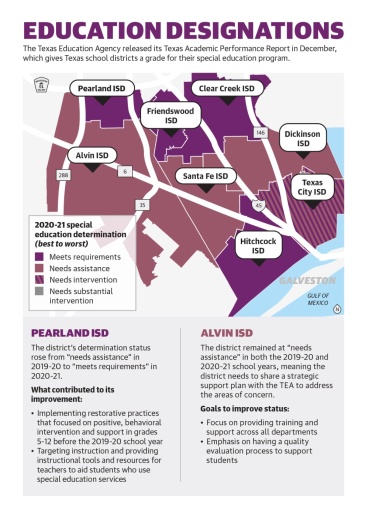

The TAPR showed while Pearland ISD improved its determination status, Alvin ISD remained at the same rank as the year prior.

For the 2020-21 school year, PISD was given a “meets requirements” status in special education, which is the highest ranking the TEA gives. For PISD, it was also an improvement from where it was in 2019-20, when it was given a status of “needs assistance.”

PISD officials said focusing on behavioral teachings helped with raising its TEA status.

“Our goal is that our students reach their highest potential,” said Lisa Nixon, the assistant superintendent of special programs at PISD.

Comparatively, Alvin ISD received the “needs assistance” designation in the 2019-20 and 2020-21 school years; nearby Santa Fe and Dickinson ISDs also received “needs assistance” in 2020-21, and Friendswood and Clear Creek ISDs met requirements in both school years.

AISD leaders plan to continue department trainings to help with the status, AISD Director of Special Education Sarah Chauvin said.

Making the grade

After both PISD and AISD were designated “needs assistance” in 2019-20, they were required to share a strategic support plan with the TEA addressing weaknesses indicated by the TAPR, district officials said.

Additionally, the TEA was in constant communication with each district, both Nixon and Chauvin said. Districts that do not meet requirements could receive additional support if needed, according to the TEA.

“If we were not [showing] improvement on our goals, then when we receive our data for next school year, then they might escalate the level of support required,” Chauvin said.

While AISD remained at “needs assistance” for 2020-21, Chauvin said the district does not anticipate that again in 2021-22 because AISD improved some of its results-driven indicators, such as representation among its special education population.

Meanwhile, PISD credited some of its status improvement to implementing a restorative practices approach, Nixon said. The plan was previously used in elementary schools only, but it expanded to fifth through 12th grades three years ago, Nixon added.

The approach emphasizes teaching and reinforcing positive behavioral intervention before issues escalate, Nixon said.

“That had an impact,” Nixon said. “I won’t say that’s the only thing, but it definitely contributed.”

Going forward, PISD and AISD officials said they plan to focus on more training, particularly in identifying and accommodating students who may need additional support.

Statewide, TEA officials told Community Impact Newspaper it has designed and implemented a new system over the last five years to monitor special education programs across Texas public schools that balances legal requirements with student outcomes.

“Students with disabilities in Texas public schools deserve high quality, effective, special and general education services,” TEA officials said.

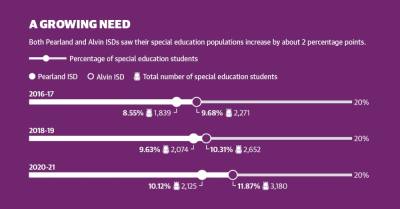

Increased enrollment

In 2016-17, PISD’s special education made up 8.55% of the overall student population. It rose to 10.12% in 2020-21. Comparatively, AISD’s special education population made up 9.68% of the overall student population in 2016-17 versus 11.87% in 2020-21.

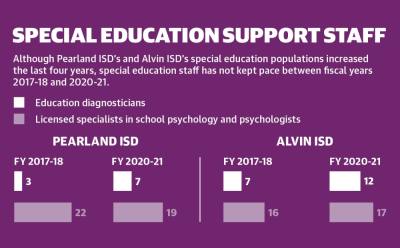

With the population increases, PISD’s and AISD’s staff has varied among its education diagnosticians as well as licensed specialists in school psychology, or LSSP, positions. Both work with students receiving special education services, AISD and PISD officials said.

PISD’s number of LSSPs and education diagnosticians varied between 2017-18 and 2020-21—losing three LSSP staff members and gaining four education diagnosticians, per district data.

Meanwhile, AISD’s LSSPs and education diagnosticians staffing has not changed much. In 2017-18, the district had 16 LSSPs and seven education diagnosticians. In 2020-21, the number of LSSPs rose by one and education diagnosticians by five.

School districts across the state are facing staffing shortages, said Linda Litzinger, public policy specialist for Texas Parent To Parent, an organization focusing on special education services in the state. This message was echoed by AISD.

“Unfortunately, there is a statewide, honestly, nationwide, shortage in LSSPs, which has impacted our ability to fill our requested positions,” Chauvin said. “We ... have two LSSP vacancies for this school year that are unfilled.”

Chauvin said AISD has combatted the shortages by filling vacancies with other personnel and collaborating with local universities to allow interns to grow under the district’s guidance—some of whom become full-time employees upon graduation and obtaining licensure.

“There is a lot of chaos because of COVID still,” Litzinger said. “And the kids with special needs are naturally going to get the short end of the stick.”