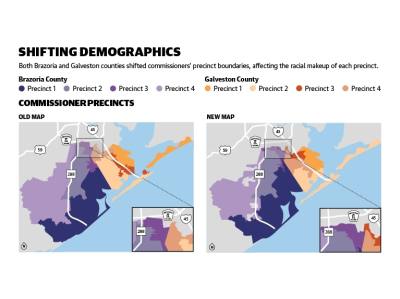

The Friendswood area is now represented by Precinct 3 in Galveston County; in Brazoria County, the boundaries for Precinct 3 have shifted with more of Pearland and less of Alvin in the new boundaries.

“We had the most radical change,” Brazoria County Precinct 3 Commissioner Stacy Adams said.

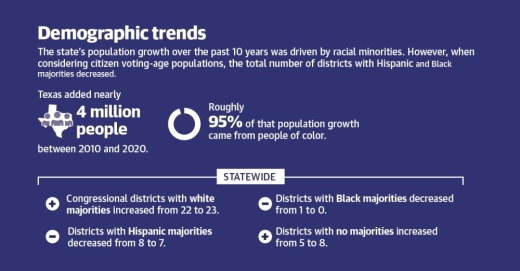

Between 2010-20, roughly 95% of population growth in Texas was driven by people of color, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau. That population growth resulted in two new congressional districts for the state for a total of 38 districts.

However, when looking at citizen voting-age populations, the number of congressional districts with white majorities across the state increased by one under the new maps from 22 to 23. At the same time, the number of districts with Hispanic majorities and Black majorities both fell by one, and the number of districts with no racial majority grew by three, according to the Texas Legislative Council.

Michael Li, a redistricting expert with the nonprofit law and policy institute Brennan Center for Justice, said the trends raise questions about potential Voting Rights Act violations.

“The real question is: Are there more opportunities for the minority communities that provided most of the state’s growth?” Li said. “There doesn’t seem to be, and that raises a lot of red flags about potential discrimination.”

The U.S. Department of Justice announced Dec. 6 it is suing the state of Texas over the new maps. The lawsuit states the new maps disenfranchise Black and Latino voters through a process called “vote dilution,” which spreads voters of color through several districts to reduce their voting power.

State Sen. Joan Huffman, •R-Houston•, who served as the chair of the Senate Redistricting Committee, defended the maps at several public hearings that were held throughout the process and said they comply with the Voting Rights Act.

“We drew these maps race blind,” Huffman said at a September public hearing on the maps. “We have not looked at any racial data as we drew these maps.”

History in the courts

Redistricting was tackled as part of a third special session of the Texas Legislature called by Gov. Greg Abbott. The session ran through Oct. 19, when the new maps were finalized.

According to the state’s redistricting website, two requirements for the process are that districts must have as close to equal population as possible and districts cannot limit voting based on race, color or language group. Under the U.S. Constitution, lines must be redrawn every decennial census.

Richard Murray, a political science professor at the University of Houston and former redistricting adviser to the Texas Legislative Black Caucus, said the process allows for redistricting committees to “crack” or “pack” populations, giving parties more control.

“We’re the only state that gained two seats in the country,” he said. “There’s immense pressure [on Republican lawmakers] to do something.”

One change to this year’s process was removing preclearance, which the U.S. Supreme Court struck down in 2013. Part of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, preclearance required states with a history of racial discrimination to submit plans to the federal government for approval.

“There’s nothing that prevents Texas from being as aggressive and discriminatory as it wants and basically daring people to go to court to get the maps struck down,” Li said. “It is a critical piece of protection that is gone now.”

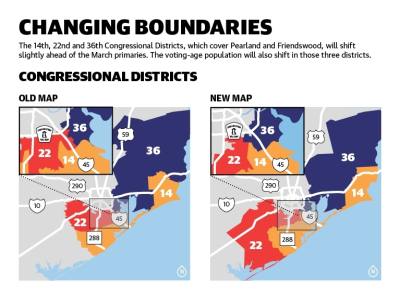

The congressional changes affected the Pearland and Friendswood area. While the Texas House and Texas Senate boundaries also shifted, they did not affect Pearland’s and Friendswood’s representation.

The 22nd Congressional District, which includes most of Pearland and is served by Republican U.S. Rep. Troy Nehls, had a 62% nonwhite voting-age population under the old maps and is now 55% nonwhite, according to the Texas Legislative Council. Likewise, Republican U.S. Rep. Randy Weber’s 14th District, which touches the Friendswood area, went from 49% to 44% nonwhite voters.

Patrizio Amezcua, a government professor at San Jacinto College in Pasadena, said demographic shifts could be effects of Republican gerrymandering and state legislators doing what they can to ensure their re-elections.

“It’s almost a way for elected officials to pick their voters rather than the other way around,” he said. “This is not a new phenomenon.”

Similarly, Amezcua said Democrats are doing the same thing at the local level, such as in Harris County Commissioners Court. On Nov. 16, two Republican Harris County commissioners, Jack Cagle and Tom Ramsey, filed a lawsuit against the county in November seeking injunctive relief in the 270th District Court. As of press time Dec. 1, Judge Dedra Davis set a date for Dec. 13 to hear arguments over an injunction.

Meanwhile, the 36th Congressional District, served by Republican U.S. Rep. Brian Babin, now includes Friendswood. An Oct. 20 release from Babin’s office stated Babin looks forward to serving the Ellington Field area.

“This unification will place Ellington Field in the same district as Johnson Space Center and all the good public servants, contractors and private sector businesses that support their mission every day,” Babin said. County changes

As officials adjusted congressional and other districts at statewide, county commissioners did the same for local precincts. The new maps will be in effect for the March primaries.

In late October, Brazoria County commissioners approved new precinct boundaries. Before the changes, populations between precincts were unbalanced: Precinct 4 had about 110,600 residents compared to Precinct 1 along the coast, which had about 74,900 residents, Adams said.

To balance the populations, part of the northern tip of Precinct 4 went to Precinct 3, and some of the southern part of Precinct 3 in Alvin went to •Precinct 1•. In total, Precinct 3 lost about 20,000 of its constituents to Precinct 1 and gained about 25,000 from Precinct 4, meaning Precinct 3—which includes portions of Pearland and Friendswood—endured the greatest change, Adams said.

“That is a pretty big shift there alone,” he said.

The voting-age population in Precinct 3 also shifted with the population of white and Hispanic voters dropping; comparatively, Black and Asian voters grew. Brazoria County hired a consultant to make sure none of its proposed boundary changes violated the law when it came to diluting minority representation, Adams said.

“Particularly when talking about minority districts, you want to keep those communities together,” Amezcua said.

In Galveston County, commissioners approved new boundaries in mid-November. Precinct 3 moved from the center and southern part of the county to the northwest near Pearland and Friendswood with Precinct 4.

Another option commissioners considered would have altered precinct boundaries less and kept Precinct 3 Commissioner Ken Clark’s and other commissioners’ representation largely the same.

Still, Clark said he prefers the map the county went with because it is cleaner with more equal populations between precincts. Before, the total population between precincts ranged from 86,502 to 95,275; now, the margin is closer with precinct populations ranging from 87,185 to 88,111, according to the county’s redistricting data.

“I think it’s an important process because it balances out [the population],” he said of redistricting.

For both counties, the new maps will not unseat any commissioner. Commissioners start the redistricting process knowing where each commissioner lives to avoid redistricting them out of their precincts, Adams said.

Amezcua said gerrymandering may occur because elected officials redraw boundaries, and they have a personal stake in ensuring their re-elections.

“It is about protecting incumbents. It is about ensuring your re-election for your party,” Amezcua said.

Adams does not see it that way.

“I don’t care about that when I’m drawing the lines,” he said. “I’m going to protect who the public elected.”

Shawn Arrajj, Jishnu Nair and Kelly Schafler contributed to this report.