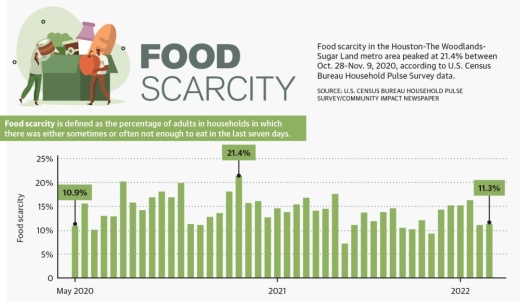

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, 10.9% of residents in the Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land metro area reported being food scarce at the start of the pandemic between April 23-May 5, 2020. Between Oct. 28-Nov. 9, 2020, local food scarcity peaked at 21.4% and has since fluctuated, dropping to 11.3% between March 30-April 11, 2022.

“There for a while in COVID[-19], [demand] seemed to kind of die down a little bit because a lot of money was being put into the community through the government,” said Millie Garrison, executive director of Humble Area Assistance Ministries. “But once that [money] stopped, [demand] just increased because now food costs have gone up; gas has gone up; and there’s no help.”

The Houston metro’s unemployment rate dropped from 13.3% in April 2020 to 4.4% in March 2022, according to Texas Workforce Commission data. However, local food bank leaders said ongoing supply chain challenges and inflation have continued to drive the demand for food assistance while making it harder to meet those needs.

Pre-existing conditions

Food insecurity has long been a challenge in the Lake Houston community even prior to the pandemic, local leaders said.

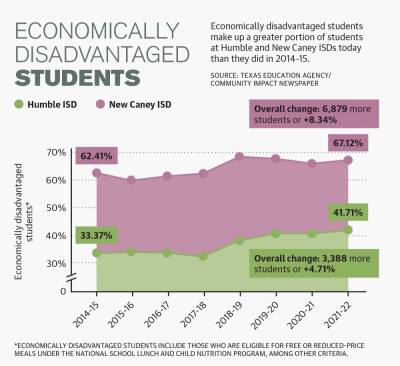

Between the 2014-15 and 2021-22 school years, the portion of students who were considered economically disadvantaged—which includes students who are eligible for free or reduced-price meals—increased from 33.37% to 41.71% in Humble ISD and from 62.41% to 67.12% in New Caney ISD, according to Texas Education Agency data.

“Food insecurity has been around for a long time. It’s not a new issue, but it’s something that’s kind of come to the top because it hit home for so many people who have never had to face hunger in their entire lives,” said Kristine Marlow, president and CEO of the Montgomery County Food Bank.

When the pandemic began, Brian Greene, president and CEO of the Houston Food Bank, said local food pantries were inundated with thousands of new clients almost overnight.

“As soon as those closures and layoffs hit, the lines went crazy long—longer than we’ve ever seen, like even after Hurricane Harvey,” Greene said.

Likewise, Marlow said the Montgomery County Food Bank nearly doubled its monthly clientele early in the pandemic from 45,000 to 88,000 clients in one month.

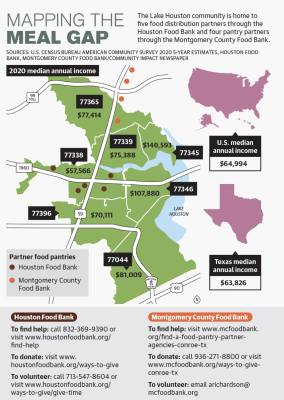

The Lake Houston community is home to five food distribution partners through the Houston Food Bank and four pantry partners through the Montgomery County Food Bank—all of which had to quickly pivot to meet the greater demand while enforcing social distancing with fewer volunteers.

Both the Houston and Montgomery County food banks as well as HAAM began hosting mobile food distributions and delivering food to vulnerable populations to meet the increased need. Additionally, contactless drive-thru distribution became commonplace, which Greene said had unexpected benefits.

“A lot of those working households did not feel comfortable going to their local church pantry because they would see their neighbors and they’d feel like they were being judged,” Greene said. “With curbside distribution, ... you drive through, pop your trunk and leave. ... So we were actually serving households that weren’t coming to us before.”

Although COVID-19 cases and unemployment claims have since declined, local food bank leaders said the demand for assistance remains high.

Ongoing challenges

Even under normal circumstances, Greene said local food banks are hard pressed to meet the demand.

“Normally, we don’t meet need even on our best day because the reality of food insecurity is that food insecurity isn’t really about food; food insecurity is about income,” Greene said.

According to the Labor Law Center, Texas is one of 20 states in the U.S. that has not raised its minimum wage over the past decade and is still at the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour. Meanwhile, the consumer price index for all urban consumers has risen by 8.5% in the past 12 months as of March 2022, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“It’s overall inflation that matters, not just food inflation. ... Food just happens to be their most flexible expense,” Greene said. “You can’t pay 90% of your rent. You can pay 90% of your food costs, [but] you’ll either just go hungry or, what usually happens is, make nutritional compromises.”

At the same time, the food banks, which pick up and deliver products for distribution via diesel trucks, are dealing with their own set of challenges as gas prices rise.

“We run over 60 trucks a day. We spend $3,000 plus on fuel per day, six days a week—and that was before the gas prices went up,” Greene said.

Meanwhile, Marlow said supply chain issues have made it harder for food banks to keep certain products such as peanut butter, frozen meat, and canned fruits and vegetables on the shelves.

“A large portion of the food we distribute is donated, but because of those increased food costs right now and supply chain issues and increased demand, the food bank has had to purchase more and more food to fill in the gaps,” Marlow said.

And while HAAM has a resale store to supplement program funding, donations are becoming fewer and further in between, meaning the nonprofit has less funding to fill in the gaps.

“There’s never enough; the donations are not coming in,” Garrison said. “For a while during COVID, everyone was cleaning out closets. ... But now, everybody is holding onto their stuff.”

Moving forward

Despite these challenges, local food bank leaders agreed their biggest hurdle is restoring the backbone of their operations—their volunteers. Greene said the Houston Food Bank had approximately 85,000 volunteers per year prepandemic and is now at about 50,000.

“The whole volunteer pool just got decimated in the pandemic,” Greene said. “Bringing those volunteers back so we can say more yeses to the difficult donations is a big way that we’re trying to adjust.”

With 37 staff members, Garrison said HAAM relies heavily on its 34 covenant congregations to supply volunteers. However, churches have likewise been slow to recover membership following the pandemic, which Garrison said means fewer volunteers to sort through donations and stock food pantry shelves.

“We’re seeing a lot of the same types of things as elsewhere—just a shortage of labor—which means the people who are committed to working here, they’re working extra hours to get the job done,” Marlow said.

This summer, Garrison said HAAM has partnered with Deerbrook Mall with plans of hosting a communitywide food fair on a monthly basis to help fill the meal gap while students are no longer in school.

Regardless of the challenges the pandemic has presented, Marlow said the work is worthwhile.

“Every person deserves to have nutritious food in their bellies, a roof over their head and clothes on their bodies,” Marlow said. “And so we’re really coming together to fill one of those basic needs.”