The rapidly declining euthanasia rate can be attributed, in part, to several programs and initiatives taken on by Harris County Pets through a partnership with Best Friends Animal Society, a national nonprofit that assists local animal services entities throughout the nation in its goal to achieve no-kill rates at shelters, said Carrie Lalonde, lifesaving program manager at the Houston division of Best Friends.

According to Lalonde, the benchmark to be considered a no-kill shelter is having at least a 90% live-release rate, which provides leeway for 10% of the animals that might require humane euthanasia due to severe medical or behavioral issues.

“[Best Friends] works directly with those shelters to develop lifesaving programming so that they are not having to kill healthy, adoptable dogs and cats,” Lalonde said. “Our work is driven by wanting to end the killing of dogs and cats in shelters by 2025.”

Harris County Pets is one of several local entities—including Texas Litter Control, the Montgomery County Animal Shelter and the Houston Bureau of Animal Regulation and Care—that have partnered with Best Friends to implement programs aimed at boosting adoption rates and curbing feral cat and stray dog populations, which Lalonde said reduces the strain on local shelters.

In January, the city of Humble announced a partnership with Texas Litter Control—a nonprofit operating out of Humble, Spring and Tomball that offers spaying and neutering and low-cost vet services—to implement a community cat pilot program.

The program—which was made possible through a $45,000 grant from Petco Love, a nonprofit division of Petco—is one of several initiatives supported by Best Friends aimed at addressing the growing feral cat populations.

Lalonde noted initiatives such as community cat programs, adoption events and long-range transports for cats and dogs have been instrumental in helping shelters achieve higher live-release rates.

Despite the availability and success of these programs, Lalonde said many areas in Houston and Harris County—including a stretch along Hwy. 59 just south of Humble near Little York Road dubbed the “corridor of cruelty”—present a different set of challenges largely related to a lack of affordable and convenient animal services.

Feral cats

Community cat initiatives have gained traction in the Greater Houston area over the last five years, Lalonde said, with Harris County Pets, Montgomery County Animal Shelter, the BARC and the Humble Animal Shelter having piloted their own programs.

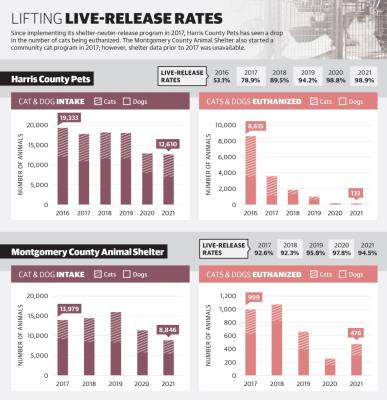

In 2017, Best Friends assisted Harris County Pets with the implementation of a shelter-neuter-return, or SNR, program that Lalonde said she believes has largely contributed to the shelter’s falling euthanasia numbers.

Through the program, cats picked up by animal control are brought to the shelter, spayed or neutered, vaccinated, ear tipped—indicating the cat has received services—and released back in the area they were picked up from if they are not identified as adoption candidates.

Of the 7,306 cats taken in by Harris County Pets in 2016, 5,127 required euthanasia; in 2021, 84 of 5,574 cats had to be euthanized.

According to Shannon Parker, Harris County Pets outreach manager, SNR programs not only prevent feral cats from breeding, but they can also curb problematic behaviors that often result in complaints to animal control. Additionally, once the cats are vaccinated for rabies, they are no longer considered a public health concern.

Deana Sellens, the executive director of Texas Litter Control, said community cat programs are replacing catch-and-kill initiatives previously employed by shelters she claims have been proven to be ineffective.

“If catch-and-kill worked, we wouldn’t have any feral cats to be complaining about,” Sellens said. “It’s just better to fix them and leave them and not let them have their three or four litters a year.”

The Humble Animal Shelter’s community cat program launched in January offers the same spaying and neutering, vaccination and ear-tip services as Harris County’s SNR program, but the free program also allows residents to humanely trap feral cats, bring them to Texas Litter Control and pick them up later in the day to release them back into the community.

Humble Animal Shelter Supervisor Lauren Hartis said the program has been in the works for several years.

“There were hundreds of cats living at the Deerbrook Mall, and a lot of them migrated from the Timberwood subdivision,” Hartis said. “Once we had them fixed, [the cats at the mall] colonized and made their own little group, and they wouldn’t let anybody else inside that group.”

Further, Hartis said keeping feral cats in cages for extended periods of time can adversely affect the other animals in the shelter.

“It makes [it] to where they get stressed out and they become sick, and when they become sick, it spreads to everybody,” she said.

Stray dogs

In Humble, while the problem of stray dogs is not as widespread as feral cats, Hartis said the most common issue the shelter runs into revolves around residents who avoid seeking out services because they think they cannot afford them.

“If you live inside the city and we know that you need help, we will spay, neuter, microchip and vaccinate your dog [for free],” she said. “If we eat the cost [of fixing them] now, it’s going to help us out in the long run when these animals aren’t running around producing extra animals for these people to provide for.”

Just south of Humble, the 14-square-mile area in northeast Houston dubbed the “corridor of cruelty” has long been teeming with stray dogs for years, many of which were abandoned by their owners, according to Beth Lovell, board chair of Corridor Rescue, a nonprofit dedicated to helping animals in the area.

“If you drive through that area at any given time, chances are you’re going to see many strays,” Lovell said. “You will see dead dogs on the side of the road that have been hit by cars. You will see dogs with broken legs that have been hit by cars, trying to survive on their own. It’s a terrible issue in that area.”

According to data provided by the BARC, nearly half of the roughly 6,000 animals that were brought to the BARC animal shelter by animal control in 2021 were strays.

Lovell noted many residents in the area simply do not have the resources to effectively take care of their animals. In many cases, Lovell said animal owners will avoid taking preventive measures such as giving their pets heartworm medication, which can lead to life-threatening illness.

In addition, Lovell said people bringing animals to the shelter are regularly turned away due to capacity issues, which she said often leads to animal dumping when pet owners think they are out of options.

“That’s when we see a lot of people take the dog to a back road and dump it,” Lovell said.

Since 2017, the BARC has confiscated almost 1,500 animals due to reports of cruelty, according to BARC data, which is often a result of malnourishment, Lovell said.

While Lovell commended measures such as community cat programs to address feral cat populations, she said dealing with stray dogs takes a more hands-on approach. To reduce overcrowding, Lovell said Corridor Rescue works with local shelters to transport adoptable dogs across state lines to animal shelters with higher demands for adoptable pets—a measure also implemented by Best Friends.

According to Lalonde, it is important to understand that a lot of perceived animal cruelty is a result of a lack of access to affordable resources.

“It’s easy to assume that an animal isn’t loved because, from your perspective, it doesn’t look like it’s well cared for, but that’s actually not true,” she said. “That animal could have an owner that deeply cares about it but just does not have the resources.”