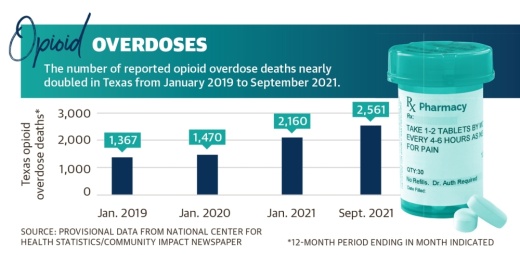

Opioid overdose deaths have steadily risen in Texas, nearly doubling from January 2019 to September 2021, according to the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics. Provisional NCHS data indicates there was an estimated 100,306 drug overdose deaths in the U.S. in 2021, an increase of 28.5%.

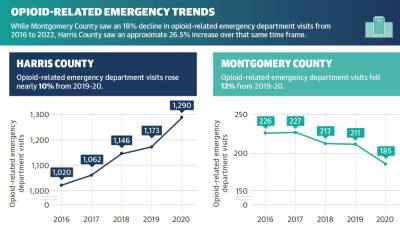

In Harris County, the number of drug overdose deaths had similarly risen from 764 in July 2020 to 1,041 in July 2021, according to NCHS data. During that same time frame, drug overdose deaths in Montgomery County increased slightly from 116 to 120.

“These are diseases of despair that we’re dealing with,” said Tyler Varisco, a health services researcher with the University of Houston. “When people are economically challenged or psychologically challenged, ... we see increased vulnerability in our communities to opioid use and other forms of substance misuse.”

Officials charged with addressing the rise of opioid-related overdoses have attributed the issue to several factors, including opioid addictions arising from legally prescribed medications, illegal pill manufacturing operations and difficulties obtaining treatment due to COVID-19.

Legally obtained prescriptions

In the late 1990s, pharmaceutical companies began marketing opioid pain relievers as drugs that were not as addictive as previously thought, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

“I think early on in this crisis, the issue was really misuse of prescriptions, and it still is to some extent,” said Ericka Brown, director of Harris County Public Health’s Community Health and Wellness Division. “Awareness [of medical providers] of alternatives to opioids for pain control ... has really done a great job of mitigating that.”

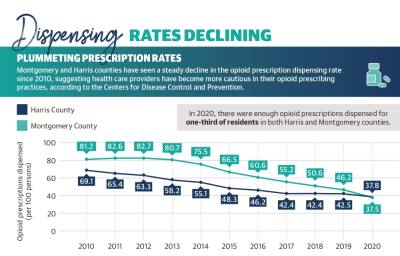

According to NCHS data, 81.2 opioid-based prescriptions were administered for every 100 people in Montgomery County in 2010. In Harris County, 69.1 prescriptions were administered for every 100 people in the same year. By 2020, those rates had fallen to 37.5 and 37.8 prescriptions per 100 residents in each county, respectively.

"This crisis has exposed cracks in the system and made them a lot more evident,” Varisco said.

However, James Campbell, chief of emergency medical services for the Montgomery County Hospital District, said he believes recent crackdowns on unnecessary opioid prescriptions have attributed to the county’s falling opioid dispensing rates.

“[Law enforcement] worked to arrest those doctors and get them out of practice, which has been a huge impact,” Campbell said.

With opioid dispensing rates falling over the last decade, Brown said Harris County Public Health’s focus has since shifted to illegally obtained opioids.

“Now, the [production] of ... lookalikes of prescription medication, I think, is overtaking the prescription medications themselves,” Brown said.

Illegal pill manufacturers

Doug Hooten—CEO of Harris County Emergency Services District 11 Mobile Healthcare, which provides emergency medical services in north Harris County, including parts of the Humble area, said many opioid overdose deaths result from individuals procuring drugs made by illegal pill manufacturers with no knowledge of what the pills contain.

“It’s just Russian roulette,” Hooten said.

Hooten said illegally manufactured pills often contain fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 80-100 times stronger than morphine. He noted fentanyl can be lethal in doses as small as the tip of a pencil.

While Hooten said illegal pill manufacturing operations are likely more widespread outside of the U.S., the practice still occurs locally.

On Feb. 18, Harris County Precinct 4 constables discovered boxes of bags filled with pills laced with fentanyl at a residence less than 10 miles from Humble as well as the equipment needed to manufacture them, according to officials with Harris County Precinct 4 Constable Mark Herman’s office.

Telehealth affects treatment

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, many health care centers were forced to shift to offering services remotely. Katy Franklin—a substance use counselor at Tri-County Behavioral Healthcare, which offers substance abuse programs in both Harris and Montgomery counties—said the transition was difficult for patients who were struggling with addiction.

“Treatment was less effective for this particular population,” Franklin said.

Additionally, Varisco noted confusion among doctors spread in the early months of the pandemic concerning what treatments were acceptable to prescribe for opioid use disorders.

A 2020 memo from Phil Wilson, the executive commissioner of Texas Health and Human Services, said buprenorphine could be prescribed virtually, but methadone required a face-to-face evaluation before the first dose could be provided. Both drugs are used to treat opioid use disorders.

“I don’t know if [the policy] was well understood by providers, and that led to lapses in our treatment,” Varisco said.

Telehealth did, however, allow some smaller clinics and private practices to expand their coverage areas where patients could not access in-person care. Lori Fiester, clinical director at Houston-based nonprofit Council on Recovery, said telehealth gave patients who were without transportation or who were immunocompromised access to care.

Government solutions

State and local entities are working to address the opioid epidemic through local funding, law enforcement resources and increased education surrounding opioid misuse.

Royce Worrell, EMS division chief of Humble Fire Rescue said Humble EMS officials have administered Narcan—a drug used to rapidly reverse the effects of opioids when overdoses are suspected—11 times thus far in 2022 and 43 times in 2021. Since its inception in September 2021, ESD 11 Mobile Healthcare has administered Naloxone, which has the same effect as Narcan, 229 times.

On Feb. 16, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton announced the state had secured a roughly $1.17 billion settlement with pharmaceutical companies AmerisourceBergen, McKesson and Cardinal.

“Texans have been devastated by the opioid crisis, and it is important that this settlement is proportioned fairly among the communities that need it most,” Paxton said in the announcement.

In October, Paxton announced a $290 million settlement with Johnson & Johnson for its use of what the state referred to as “deceptive marketing tactics” that helped contribute to the crisis.

Court documents show Harris County secured $3.9 million through the Johnson & Johnson settlement, while Montgomery County is slated to receive $2.7 million. The city of Humble is expected to receive $74,000. To date, Texas has secured around $1.89 billion from opioid settlements.

A list of funding uses provided by the attorney general’s office includes community drug disposal programs, training for first responders, and youth-focused programs aimed at discouraging and preventing drug use.

Ally Bolender and Danica Lloyd contributed to this report.