Some law enforcement officers have attributed the rise in murders to the COVID-19 pandemic and bail bond practices. At the same time, Gov. Greg Abbott has made fixing what he called a “broken” bail bond system an emergency item during the 87th Texas Legislature, citing the increasing crime rates as evidence of a problem.

But trend details suggest the coronavirus pandemic and economic downturn are bigger factors, said Colin Cepuran, a senior justice research policy analyst with the Harris County Justice Administration Department. The department released a study in March that Cepuran said presents evidence there is no compelling relationship between misdemeanor bail reform and the violent crime trends.

“[There] is some evidence that misdemeanor bail reform may have actually contributed to public safety during this unparalleled time of economic and public health deprivation in Harris County,” he said.

As state legislators look at ways to make it harder for people to be let out on bond, county officials are pushing for a more restorative approach, including helping crime survivors heal and intervening in violent crime before it can be committed.

Diving into the data

Violent crimes in Harris County such as murder and aggravated assault rose between 2019 and 2020, while robberies saw a smaller increase and sexual assaults dropped, according to the study. However, increases in crime tended to be concentrated in certain communities.

In the Lake Houston area, most crimes increased, but aggravated assaults jumped almost 22%—from 216 in 2019 to 263 in 2020—according to Community Crime Map data, which compiles crime information from law enforcement agencies. Data was collected between Hwy. 59 to Atascocita and FM 1485 to Beltway 8.

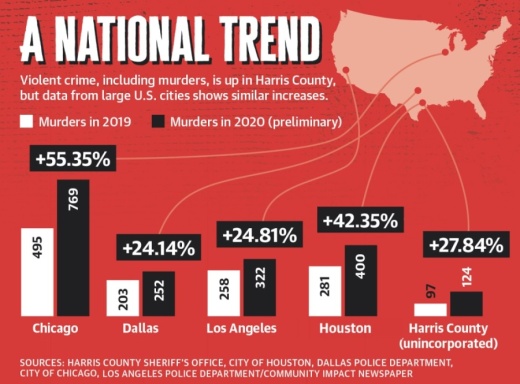

Cepuran said a study into the timing of the crime increase in Harris County, the coronavirus pandemic and the use of unsecured bonds further suggested the pandemic to be the main factor rather than the county’s misdemeanor bail reform. The justice administration department’s study showed similar violent crime trends taking place in Dallas, Chicago and Los Angeles—places where no bail reform has taken place.

Harris County first started to reform its misdemeanor bail bond practices in 2017 after a federal judge ruled the county was unconstitutionally holding people in jail pretrial for being unable to afford bail. After a lawsuit was settled in 2019, the county was required to start releasing most nonviolent misdemeanor arrestees on general order bonds.

“The socioeconomic pressures that Harris County residents [face] and increases in COVID-19 cases are both positively associated with increases in murders the next month,” Cepuran said. “The greater use of unsecured bonds—the principal effect of bail reform—actually is associated with a decrease in murders the next month.”

Montgomery County also saw up to a 5% increase in aggravated assaults and robberies from 2019 to 2020, but sexual assaults declined and murders rose by one case during that time, according to data from the Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office.

However, MCSO Lt. Scott Spencer said via email that most violent crimes have declined countywide since 2017. To ensure courts did not stall last year, the county streamlined hearings and bonds with teleconferencing and videoconferencing, extended court deadlines and reduced jail admissions for low-level offenses, he said.

“Our law enforcement leaders recognized the difficulty and complexity in dealing with COVID-19 while maintaining the effective operation of the criminal justice system,” Spencer said.

A complex problem

Critics of Harris County’s bail practices say the increase in crime has less to do with the misdemeanor bail reform at the center of the justice administration department study and more to do with decisions made by felony court judges to release people on low-cost bonds.

State Sen. Joan Huffman, R-Houston, filed Senate Bill 21, which would make it more difficult for people accused of violent offenses to get out on bail. At a bill committee hearing March 18, Cepuran said he feared it would overwhelm Harris County’s jail and leave the county exposed to costly litigation. Huffman said she expects the bill’s language to change to comply with federal court decisions.

Harris County Precinct 4 Constable Mark Herman, whose department serves Atascocita, also blamed judges for practices he said have led to more criminals on the street.

“We’re arresting someone for [driving while intoxicated], and then three nights later we’re arresting the same person again,” Herman said.

Justice administration department officials said the county is working to determine what information judges have available to them when deciding how to set bonds.

Drew Willey, founder and CEO for Houston nonprofit Restoring Justice, which serves the incarcerated community, said she believes claims that affordable bonds lead to higher crime rates are incorrect.

“Data suggests that socioeconomic pressures present nationwide are responsible for increases in crime—not local policy changes like bail reform,” Willey said. “It is irresponsible for law enforcement to suggest otherwise and drive a narrative of fear into our community.”

Violence interruption

In the March report, the county’s justice administration department also presented thoughts on how the rise in crime can be addressed.

The department’s in-progress programs will focus on violence interruption and helping survivors of crime—methods that are intended to address the increase in violent crime at its roots, Deputy Director Ana Yáñez Correa said.

“If the threat of having a felony was as effective as people have instinctively thought, then we probably would not see the increase in these types of crimes,” she said.

On March 30, Harris County commissioners invested $3 million into overtime pay for law enforcement to target violent criminals.

“This is an opportunity to provide the sheriff the resources to start bringing justice and a jailhouse to those violent offenders,” Harris County Precinct 2 Commissioner Adrian Garcia said at the meeting.

A violence interruption study is almost complete, Cepuron said. The program will intervene when individuals are most likely to experience or perpetuate violence and just after individuals experienced violence.

As more people are vaccinated, Chelsey Narvey, an assistant professor in the Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology at Sam Houston State University, said the resumption of face-to-face services for offenders and survivors could help steer people away from violent acts.

“As we move forward and the ... rehabilitation and treatment programming starts to pick back up again, we might hopefully see that the recent uptick in crime starts to trend down,” she said.

Kelly Schafler contributed to this report.

Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly attributed the information from Restoring Justice. The article has been updated to attribute the information to Drew Willey, founder and CEO of Restoring Justice.