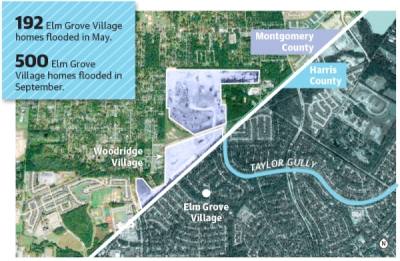

Last year the Lake Houston area was hit with heavy rainstorms May 7-9 and by Tropical Storm Imelda on Sept. 19. During both events, hundreds of homes in north Kingwood neighborhoods flooded—with many homeowners blaming the Woodridge Village development located on the boundary between Harris and Montgomery counties.

Preliminary drawings for the 268-acre development showed more than 800 residential lots planned, according to plat information from the Montgomery County engineer’s office.

The neighborhood of Elm Grove Village reportedly did not flood in any other rain event in recent decades until development began just north of the community, said Beth Guide, a director of the Elm Grove Village Community Association, a homeowners association.

“We didn’t flood during Hurricane Harvey; we did not flood during Tax Day flood; we didn’t flood in 1994; we didn’t flood in [Tropical Storm] Allison—I mean, we’ve never flooded,” she said.

While flood-mitigation efforts are ongoing on nearby streams, Houston City Council Member Dave Martin said he hopes the land can be purchased and reverted into green space.

“Our ideal situation would be if they discontinue building houses in that program and allow the city and the county to entertain the purchase of that land and having us turn it back into green space and also create detention,” Martin said.

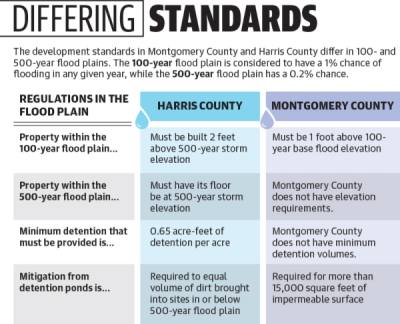

Development standards

After the May flood, hundreds of homeowners in Elm Grove Village and North Kingwood Forest filed lawsuits against Figure Four Partners—a subsidiary of Perry Homes—and several connected parties May 14, according to court documents filed in the Harris County District Court.The lawsuit claimed Houston-based PWSA Inc., general contractor Rebel Contractors Inc. and Figure Four Partners caused their homes to flood when they cleared trees and vegetation without building detention. There were no updates on the lawsuit as of press time.

However, Montgomery County Engineer Jeff Johnson said he believes the Kingwood area would have flooded in May and Imelda regardless of the development, in part because of the intense rainfall in the area.

The May event dropped between 5-9 inches of rain on portions of the Lake Houston area in a six-hour period on May 7, while Imelda dropped 14-29 inches of rain Sept. 17-19, according to Harris County Flood Warning System rain gauge data.

Johnson also said he believes federal development standards are set to a “hypothetical” 100-year storm event—or a storm that has a 1% chance of occurring every year—which does not accurately represent what is seen locally.

“They’re all wanting to blame Montgomery County for allowing developers to do what they’re doing all over the nation,” he said.

The Woodridge Village development is not within the Montgomery County’s 100- or 500-year flood plain; however, Elm Grove Village is in Harris County’s flood plain.

Johnson said the dichotomy between the flood plain mapping is because Montgomery County’s “outdated” maps have not been redrawn since the 1970s.

Meanwhile, Harris County’s flood plain maps were updated more frequently in 2007, which is why portions of Elm Grove Village are in the 100-year flood plain, said Matt Zeve, the deputy executive director of the Harris County Flood Control District. Harris County is updating its maps again, and the preliminary maps could be ready by summer 2022, Zeve said.

Johnson said he believes redrawing Montgomery County’s flood plain maps would be too expensive. He said he believes the federal government should pay for the county’s flood plain maps to be redrawn.

“The federal government is telling us Woodridge [Village] is not in a flood plain, but right across the county line, the federal government is telling Harris County that you people [in Elm Grove] are in the flood plain,” he said. “So it’s a federal problem. It’s nothing the local government can solve.”

Negotiating a deal

Perry Homes officials approached the Harris County Flood Control District in late 2019 offering to let the county purchase the land, said Joe Stinebaker, the director of communications for Harris County Precinct 4 Commissioner Jack Cagle’s office.Due to the property’s location in Montgomery County and its alleged effects on Harris County property, the acquisition would need to be completed through a partnership with Montgomery County, the HCFCD, the city of Houston and Perry Homes, Stinebaker said.

“It’ll take an unusual partnership to get a project like this done, but Harvey and [Hurricane] Ike and Memorial Day [2015 flooding] and Tax Day [2016 flooding] ... have provided the incentive to do the unusual,” he said.

Figure Four Partners said in a statement that allowing government entities to purchase the land from the company is a potential solution.

“Figure Four said many months ago that we would consider alternatives that would provide more robust mitigation, and we believe this concept reflects a meaningful and impactful solution,” the statement read.

The company declined to comment on the asking price for the acquisition or whether it would accept equal or less of what was paid for the property.

“No one is interested in Perry Homes making a profit off county taxpayers as a result of this flooding problem,” Stinebaker said. “What Commissioner Cagle is interested in is trying to get as many people out of harm’s way as cheaply as possible.”

City and county officials were unable to provide a proposed timeline for the negotiations. The acquisition would be Harris County’s second flood-mitigation projects outside of county lines if approved by all parties, but it will likely not be the last, Zeve said.

The district’s $2.7 million San Jacinto Regional Watershed Master Drainage Plan study, which began in April 2019 and is set to be completed in September, will determine other potential land acquisitions and flood-mitigation projects outside of Harris County, he said.

As for the Perry Homes property, Zeve said $18.7 million of the county’s $2.5 billion flood infrastructure bond, which voters approved in August 2018, is reserved for partnership projects in the San Jacinto River watershed. The money could be used to partially fund the acquisition, he said.

Detention or green space

Depending on negotiations, the Woodridge Village property could either be built out into the planned residential development with five detention basins or be transformed into a much larger detention basin with possible green space, Zeve said.“What that [detention] would look like, how big it would be, what type—if any—of amenities would be there is totally unknown at this time,” he said.

Per a written agreement with the city of Houston, Figure Four Partners agreed in mid-October to install all five detention ponds on the project before moving forward on other construction. As of mid-February, Martin said one basin has been completed, and a second is roughly 50% completed.

However, since the land purchase option was broached in late 2019, Martin said Woodridge Village developers have stopped digging detention ponds as to not invest further funds in the property.

While Martin said he would like for the negotiations to end soon, he said he does not want the city to be pressured into paying more than necessary for the property.

“I know the clock is ticking. ... They’re losing money every day they’re not doing anything with the land—I totally understand that,” Martin said. “But we are not going to be pressured into a deal that doesn’t fit what we think should be the remediation of the land as well as what the purchase price should be.”

Guide, one of the Elm Grove Village HOA directors, said she does not believe building five retention ponds will stop future flooding.

“[The acquisition is] the only feasible solution; it’s the only way Elm Grove can remain a neighborhood,” Guide said. “Any other way, we’re just going to keep flooding every time.”