Houston’s air quality and ozone levels have improved over the last 25 years, experts say.

According to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, from 2000 to 2016, the Houston-Galveston-Brazoria population increased by 44 percent, while ground-level ozone levels improved by 29 percent. Despite this progress, Houston is still not meeting Environmental Protection Agency standards.

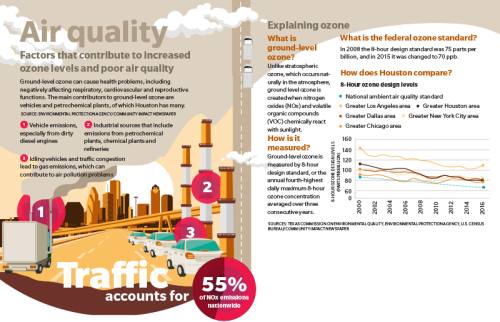

Stuart Mueller, operations manager for Harris County Pollution Control Services, said TCEQ released rules in the early 2000s regarding nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds—which can be precursors to ozone formation—that contributed to the decline in ozone.

However, ozone pollution remains to be a challenge, as the standards continue to be made more stringent, TCEQ Media Relations Specialist Andrew Keese said. According to the American Lung Association, Houston has the 12th highest ozone level of all U.S. cities.

“We are getting this uptick in pollution—not anywhere near the levels that we saw 10, 15 years ago—but it isn’t on that same steady decline that we had been seeing,” said Stephanie Thomas, a Houston-based organizer and researcher for Public Citizen, a nonprofit political advocacy organization.

Houston-Galveston Area Council experts anticipate, under the EPA’s 2008 standards and based on previous years’ emissions from previous years, the EPA will reclassify Houston as “serious” this summer, meaning the region’s air quality has not improved enough to meet EPA standards.

“We have a ways to go [to improve air quality in Houston],” H-GAC Air Quality Manager Shelley Whitworth said.

Pollutants critical to Houston

The Clean Air Act, a federal law passed in 1970 to control air quality, makes it a requirement for the EPA to issue standards known as the National Ambient Air Quality Standards for six criteria pollutants, according to the EPA’s website.

Experts say two of the most critical to Houston are particulate matter and ground-level ozone. Different from stratospheric ozone—which is found naturally in the atmosphere—ground-level ozone is created from natural and man-made chemical compounds and pollutants, according to the TCEQ.

Keese said the TCEQ uses its network of regional ozone monitors across the Greater Houston area to track emissions. While the city is meeting EPA standards with five of the six NAAQS, Houston has never met ozone standards.

“Under current law, the EPA is required to review these standards every five years,” said U.S. Rep. District 22 Pete Olson, R-Sugar Land. “We could not hit that goal in five years despite making all this progress.”

To make it easier for states to comply with new ozone standards, Olson has been working on House Resolution 806, the Ozone Standards Implementation Act, which has passed in the House, but not the Senate.

High ozone levels can negatively affect respiratory, cardiovascular and reproductive functions, Thomas said.

Ozone is not the only air quality concern. According to the ALA, Houston was ranked 16 out of 184 metropolitan areas nationwide for annual particle pollution, which involves dirty, smoky particles from exhaust emissions. Particulate matter can affect the heart and lungs and cause serious health effects.

Harris County’s average daily density of fine particulate matter is the highest of any Texas county, while Montgomery County has the third-highest, according to data from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a health care nonprofit.

“We are watching [particulate matter density] very closely,” Houston Health Department Scientist Loren Raun said.

Air pollution solutions

Considering the progress the city has made, Whitworth said Houston’s inability to meet the standard for ozone proves other solutions need to be looked at.

“We really have to look at just everything across the board,” Whitworth said. “Because so much has already been done in industry now, we are looking a lot more closely at our vehicles.”

Thomas said TCEQ’s Texas Emissions Reduction Plan could help address vehicle emissions. The program helps companies and government agencies apply for funding for cleaner vehicles.

“If you are driving a truck that is 20 years old, you are going to be contributing significantly more air pollution than a truck that is a year old,” she said.

When improving roadways, Harris County officials also have to consider vehicle emissions, said Pamela Rocchi, director of Harris County Precinct 4’s Capital Improvement Projects Division.

“Roadway improvements may not be constructed without taking precautions to achieve control of dust emissions,” Rocchi said. “Air pollution from road construction rules are enforced by the [TCEQ] under Title 30 [of the] Texas Administrative Code.”

In addition to proposed solutions and the implementation of EPA and TCEQ rules, Whitworth said residents can help reduce emissions by carpooling.

“We are a major metropolitan area, [and] we are developing [a] more suburban system,” she said. “We need folks to learn to change their way of thinking.”

Latrice Babin, deputy director of Harris County Pollution Control Services, said she agrees mass transit can help.

“People think our air quality issues are the burden and responsibility of industry, but we all have a part to play in that. When you drive your vehicle, when you idle your vehicle—all of those things contribute to the soup that is ozone and the air quality of our area,” Babin said.

The department receives about 1,500 pollution complaints annually that it investigates, about half of which involve air quality, Babin said. It also monitors air permits for industrial facilities, keeps track of 12 ozone monitors countywide—including one in Atascocita—and offers education and outreach.

“Air permits are in place for industrial facilities, but each person has to do their little bit,” she said.