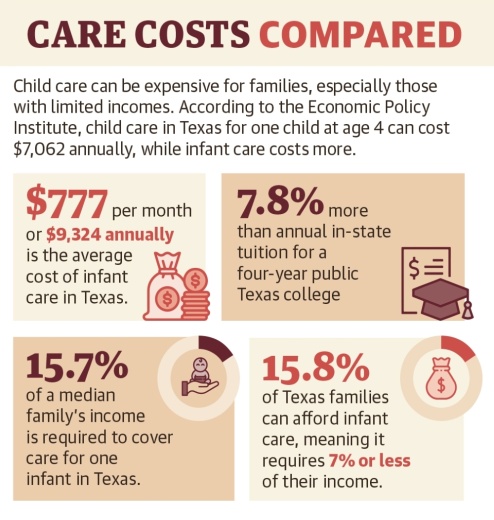

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, child care is considered unaffordable if it requires more than 7% of a family’s income. Yet as of October 2020, the typical Texas family was paying 15.7% of its income for infant care for one child, according to the Economic Policy Institute. By the 7% standard, 15.8% of Texas families could afford infant care.

However, the cost of child care was rising even before the pandemic, according to Kim Kofron, the director of early childhood education with Texas-based nonprofit Children at Risk.

Kingwood resident Stephanie Fowler and her husband, Drew Fowler, are both working parents with three young children.

"We actually pay more in child care than we do for our mortgage and student loans,” Stephanie Fowler said.

Meanwhile, many child care workers are not receiving high enough wages, and day cares are also seeing increased costs of supplies due to inflation, according to Shuang Xu, an economics professor at Lone Star College-Kingwood.

“If you really look at the supply and demand for the industry, something’s really, really wrong,” Xu said. “On one end, we have parents complaining cost is too high; on the other end, we have workers complaining pay is too low. So somewhere it’s not adding up.”

High costs for parents

As of October 2020, the average cost of infant care in Texas was $777 per month, or $9,324 annually—7.8% more expensive than annual in-state tuition for a four-year public college in Texas, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Meanwhile, the average cost of child care for a 4-year-old is $589 per month and $7,062 per year.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Consumer Price Index cost for child care rose 5.1% from January 2020 to February 2022.

Stephanie Fowler said she and her husband pay between an estimated $1,200-$1,300 per month so their 2-year-old can attend preschool in Kingwood. The family also has an infant and a 6-year-old in first grade, who are watched by a nanny when their parents are working.

“It’s an important cost,” she said. “There are less expensive options in the area, but it’s hard. You’re leaving your kids with somebody for eight to 12 hours a day, so you really want to make sure that you found a place ... that’s going to sort of raise them the way that you would while you’re not there.”

Pandemic issues

While parents are spending more on child care than they were two years ago, child care centers are facing higher costs and other industry issues related to the ongoing pandemic.

Some day care centers were forced to permanently close due to financial hardships induced by the pandemic, exacerbating child care deserts—ZIP codes with fewer than 36 child care seats per 100 children of working parents, according to Children at Risk. While most ZIP codes in the Lake Houston area meet CAR’s standards, 77365 falls below with 15-25 seats for every 100 children as of February.

For Primrose School at Summerwood, the initial wave of the pandemic decreased enrollment from 180 students daily to 30, franchise owner Brandi Muse said. While the school did not have to let any staff go during this time, Muse said, inflation forced the school to increase tuition.

“We did have to take a slight increase in our tuition,” Muse said. “Prices for food, paper goods, fuel, shipping, monthly school supply orders, etc. have all increased due to the pandemic. There is a labor shortage in many industries, including child care, that has resulted in higher payrolls for the schools.”

At the Lamb of God Church’s preschool in Humble, enrollment dropped from 175 students to 70, according to Preschool Director Sondra Johnson.

“We had to increase pricing to meet expenses and budget due to inflation,” Johnson said. “Which was not a huge increase because we can’t afford to lose families at this time, and we know situations are tough for families as well.”

As much as 60%-65% of a day care’s income is usually used to pay employees, Kofran said.

“When you’re taking care of little ones, you need more people. We can cram 500 [college] students with one professor, but we can’t do that when it’s babies,” Kofran said.

However, the child care industry is also facing a shortage of qualified workers, Muse said.

A survey released in September 2021 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children reported 86% of child care centers in Texas are experiencing a staffing shortage; 79% of those surveyed identified wages as the main recruitment challenge.

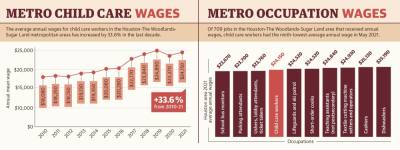

In May 2021, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported the average annual wage for a child care worker in the Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land metropolitan area was $24,150—the ninth lowest-paying occupation out of the 709 occupations in the region that receive an annual wage.

“The pay is just not there to meet those higher-costing educations,” Xu said. “This student might have $30,000-$40,000 of student loan debt, but the median pay ... for child care in Texas is $24,000 a year.”

Resources for families

An initiative through the American Rescue Plan Act offered to aid families during the pandemic was the 2021 Advance Child Tax Credit payment, which allowed parents to receive an average $250-$300 monthly payment per child starting July 15, according to the Internal Revenue Service. The payments were advances of about 50% of the child tax credit parents would have received in 2022 on their federal income tax returns.

The Advance Child Tax Credit payments offered financial relief to U.S. working families with annual incomes under $112,000-$150,000 up until December. President Joe Biden has proposed renewing the initiative for “years and years to come,” according to The White House, but the payments have yet to be extended.

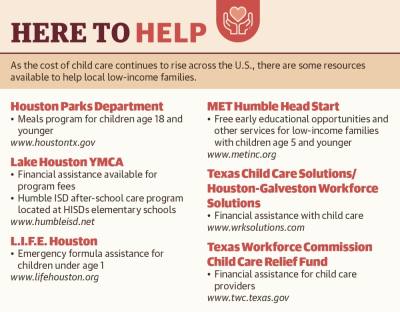

For families struggling to afford child care, there are some other federally funded options available through the Administration for Children and Families.

Early Head Start, which serves pregnant women or families with children under age 3, and Head Start, which serves families with children ages 3-5, offer low-income families free early educational opportunities and services.

Additionally, Humble ISD partners with the Lake Houston YMCA to offer after-school care at the district’s elementary schools for students in grades K-5. The program is available for district parents on weekdays after school; financial assistance is available.

Making child care more accessible is important, Kofran said, and right now, 1 in 9 children who qualify for federal assistance are receiving funds.

“We’ve adopted this public good for our K-12 system, and not that we need to replicate our K-12 system for child care, but ... it really takes all of us to support young families so that they can make the best choices for their family,” Kofran said.

Ally Bolender contributed to this report.