Executive Director and founder Kim Brusatori said most families could not take family members home—with reasons ranging from not having space to fear of exposing their loved one with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities, or IDD, to COVID-19.

Despite the center’s best efforts, the assisted-living facility had an outbreak in early April, Brusatori said. Chief Financial Officer Kristy Conrad lived in an RV outside the center for 28 days to care for clients—all of whom made full recoveries.

“We made a decision that regardless of the outcome, we were going to get our guys through it. And we walked in that home and did our best to do that,” Conrad said. “Statistically, our population should not have gotten through it like we did.”

Studies show people with IDD are more likely to contract COVID-19 due to residential group settings as well as sometimes having other medical diagnoses. People with IDD and COVID-19 are among those with the highest morbidity risk, yet they have not been explicitly prioritized for vaccines.

In the pandemic, people with IDD face heightened physical and emotional health risks, said Scott Daigle, public policy director at the Texas Council for Developmental Disabilities, a federally funded agency seeking policy change for the IDD community.

“People with disabilities are experiencing the pandemic like we all are, but many of the issues that we’re all facing are impacting people with disabilities disproportionately because of the disruptions to their basic needs,” Daigle said.

Adapting to the pandemic

While the pandemic has isolated everyone, some individuals with IDD have also faced limited access to resources, transportation and health care, Daigle said.

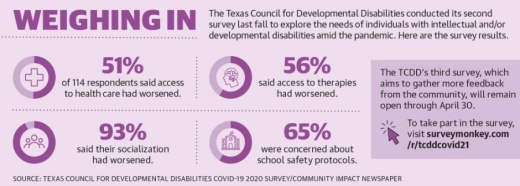

A TCDD survey conducted in the fall and released in late September showed 51% of 114 respondents said access to health care and therapies had worsened since the pandemic began; 93% said their socialization had worsened.

Some Harris County and Lake Houston-area organizations have begun reopening to continue offering in-person services to adults and children with IDD. However, some organizations remain virtual.

Officials at the Harris Center for Mental Health and IDD, the local IDD authority, said the IDD center has been closed amid the pandemic, but the center is offering virtual services. The state-funded center provides early-childhood intervention services, intake and eligibility screenings, residential living options and day habilitation programs, to name a few, to about 7,500 individuals a month, officials said.

While offering virtual services has posed challenges, participation has remained consistent in most programs, said Robert Stakem, vice president of the IDD division at the center.

“We have found that a lot of our families, for transportation to one of our programs, if they come by bus, it could be a couple of bus stops, or it could be fighting traffic,” he said. “Well, they don’t have to do that now. So many of them found that they almost prefer the virtual services.”

For organizations that have transitioned to in-person services, officials said they still worry about their clients being exposed to COVID-19 while balancing the mental and emotional effects a lack of socialization and stress can have on people with IDD.

Including Kids Autism Center reopened its Atascocita center in May under strict sanitary and safety guidelines. Executive Director and founder Jennifer Dantzler said a key part of her organization is including children and young adults with autism in the community through events and programs—which can be difficult in a pandemic.

“It’s very hard to work on communication skills ... when we’re wearing a mask and trying to teach our clients,” she said. “When we’re working on things like reading facial expressions and emotions and they can’t see 70% of your face, that’s hard.”

Atascocita resident Rhia Fehrmann said her 6-year-old son, Keller, returned to in-person learning at Including Kids in May. Keller, who was diagnosed with autism and is nonverbal, was frustrated by virtual learning, Fehrmann said, which made the decision to send him back to in-person learning a better choice for the family—despite worries about the virus.

“We didn’t really think twice about it,” she said. “Keller just thrives so much better if he has a mental challenge, and he wasn’t getting that at home.”

Vaccine prioritization

A November study from FAIR Health White Paper, a nonprofit that collects data from private health insurance claims, evaluated mortality risks for COVID-19 patients. The study showed patients with developmental disabilities were about three times more likely to die than patients without disabilities.

In January, the Texas Health and Human Services Commission also released a study on COVID-19’s effect on vulnerable populations. It referenced a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that said people with IDD were at high risk of contracting COVID-19, independent of underlying chronic conditions.

Despite this, when the CDC issued recommendations in December on vaccine prioritization, its list of people who should be prioritized did not include those with IDD.

The list was revised Dec. 23 to include people with Down syndrome, but the recommendations still exclude other disabilities, said Emily Hotez, assistant professor at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine and a developmental psychologist researcher who focuses on autistic adult development. This led to confusion on who is eligible for vaccines, she said during a TCDD virtual event March 11.

Hotez said she believes the exclusion can be tied to a stigma surrounding disabilities, which has resulted in people with intellectual disabilities partaking in only 2% of clinical trials. A study observed that of 300 randomized clinical trials, most people with ID could have participated in at least 70% of studies with minor procedural modifications, she said.

“Individuals with IDD are often dismissed as simply too complicated to treat in primary care setting, which unfortunately means that they miss out on really important preventive care,” she said.

Diagle called it “problematic” that vaccine appointments are difficult to secure and not specifically allocated to more people with IDD.

“At the very beginning of the vaccine rollout, there did seem to be a focus on going into ... those congregate care facilities,” he said. “But there were also a lot of people in the community with disabilities who also need access to the vaccine.”

In February, the Texas Department of State Health Services partnered with Austin-based Tarrytown Pharmacy to open single-day clinics at 37 sites across the state, several of which will be in the Houston area. Tarrytown Pharmacy officials said in an email that the company will inoculate up to 22,000 people with IDD and their caregivers by April 2.

The allocations are specifically for those receiving the Home and Community-based Services Medicaid waiver, officials said.

State assistance, legislative priorities

Although the 87th Texas Legislature is focusing mainly on the COVID-19 pandemic and February winter storm, there are some bills that disability advocates said could benefit the community.

For instance, House Bill 797 would allow home health nurses and hospice agencies to administer the vaccine to their patients with disabilities; HB 2312 would track immunization rates of employees and residents in long-term care facilities.

However, long-term challenges exist in how the state provides and finances services for individuals with IDD. Texas had the largest Medicaid Waiver Interest List and the most year-over-year growth among U.S. states in 2017 versus 2016, according to a February 2020 report from United Cerebral Palsy, a disability advocacy organization.

The state’s Medicaid Waiver Interest List allows people to join a waiting list to apply for waivers to access disability services, including therapy, day habilitation programs, living options and nursing and attendant care. According to January data from the HHSC, the list is 171,136 names and up to 15 years long.

“[You are] just signing up because [you are] interested in the waivers,” said Cindy Wooldridge, case manager at nonprofit health organization Easter Seals Greater Houston. “Then when you come up off the list, that’s when the application process starts.”

Wooldridge said the application process can take up to five months and end in the applicant not being eligible for services.

There have been inquiries into allowing more Texans to receive waivers, therefore decreasing the size of the Waiver Interest List. A HHSC study completed in September recommended the state gather more information on the current needs for disability services and ensure the people on the list still were interested in receiving services.

Brusatori estimated the state funds 50% of The Village Centers’ annual operation costs with the nonprofit fundraising the rest. The nonprofit needs to raise close to $2 million this year to continue offering services, she said.

Brusatori said many families with loved ones who use the nonprofit’s services rely on Medicaid or private pay—which is often outside of a family’s financial ability. The nonprofit gets $32 a day from the state for each client for day habilitation—an amount that has not increased despite added sanitation and protective equipment costs during the pandemic.

“[We] could probably ... make a lot of money by charging private pay, but we don’t do that because the parents need us to use the money that they get from the state,” she said. “Unfortunately, the money that we get from the state is not enough.”