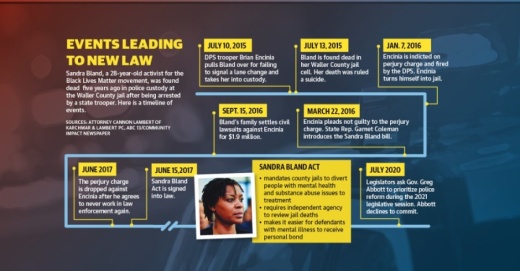

Bland, 28, was found hanging in her jail cell three days after state trooper Brian Encinia arrested her after a routine traffic stop July 10, 2015. Her death was ruled a suicide.

Encinia stopped Bland after she failed to signal a lane change, and the stop quickly escalated to an argument when Bland initially refused to put out her cigarette, according to dashcam footage. Encinia later claimed he feared for his safety during the stop, but dashcam footage and a 39-second video shot by Bland depict an excessive use of force by Encinia.

A federal wrongful death lawsuit filed against Encinia by Geneva Reed-Veal, Bland’s mother, contended Bland should not have been arrested.

Waller County and the Texas Department of Public Safety settled the lawsuit for $1.9 million and agreed to make policy changes, but the results were disappointing, Bland’s family lawyer Cannon Lambert said.

Two years after Bland’s death, two state lawmakers filed the 2017 Sandra Bland Act to address racial profiling during traffic stops, ban police from stopping drivers on traffic violations as a pretext to investigate other potential crimes, limit police searches of vehicles, and other jail and policing reforms.

The bill’s second component included efforts to increase resources for people with mental health issues or substance abuse issues and facilitated defendant’s ability to receive personal bonds.

However, the racial profiling and police training component was largely stripped by the time the Legislature passed it, and the Sandra Bland Act become mostly a mental health bill, Lambert said.

Rep. Garnet Coleman, D-Houston, and State Sen. John Whitmire, D-Houston, who authored the Sandra Bland Act, announced in mid-June that they will be committed during Texas’ 2021 legislative session to passing policies that will improve the criminal justice system.

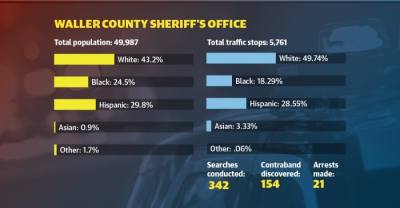

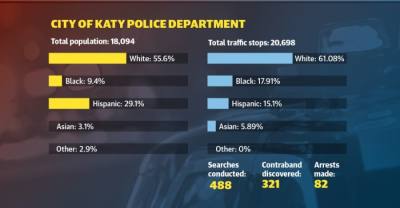

Neither the Fulshear and Katy police departments nor the Waller County Sheriff’s Office could be reached to comment on whether policy or de-escalation training has changed since Bland’s death.

“Progress is slow, but we are making it,” Lambert said. “I refuse to adopt a notion that we don’t have hope, but I do know we are not where we should be, and it is in part because we can’t even collectively accept truth.”

Building trust

Texas Southern University professor David Baker said though the Sandra Bland Act is a step forward to address a complex issue in the criminal justice system, it does not address racial profiling on a regular basis.“It is absolutely imperative that local police departments and district attorneys investigate, arrest, and prosecute officers who violate the rights of the people who live in the communities they are charged to serve,” Baker said.

The nation needs changes in law enforcement hiring practices to expose implicit bias, Baker said.

Lambert said one issue with policing in the U.S. is the rarity of police officers going into their communities to build rapport and teach young children, especially young Black children, that police are not the enemy. Rather, Lambert said, police officers are often out looking for someone doing wrong rather than helping people when they need it.

Katy Police Department Chief Noe Diaz has previously told Community Impact Newspaper the department’s shifts and policing areas are set up so the community can get to know at least one police officer by name to build trust, especially in young people.

Terrence Bufford, a Houston-area minister, said he has experienced several instances starting as a child when he was personally harassed or assaulted by a police officer, and it deeply ingrained mistrust.

“As young Black youth at the time, how were we supposed to garner a positive light on the police if the only interaction we have with these guys is based on lies and intimidation?” Bufford said. “If every time you see us, your only statement to us is, ‘We’re going to arrest you,’ or, ‘Go home,’ you’re not telling us that you are ‘Officer Friendly.’”

Cmdr. Paul Follis, a member of the Houston Police Department who lives in Katy, said he understands people are hurting from years of police violence and that diversity in a department can help work toward more equal treatment for Black people and other minorities.

“It’s easier when you have someone in your department who can explain these things to you and help make decisions and spread that knowledge,” he said. “You can’t be a majority-white police department in a minority community and expect to be successful.”

Making progress

Lambert said the final passage of the Sandra Bland Act was disappointing for both him and Bland’s family.“I think Rep. Coleman started with a clear-headed vision in addressing the de-escalation technique and mental health,” Lambert said. “There isn’t anything wrong with seeing progress on the mental health side of it, but to ignore de-escalation techniques in the Sandra Bland Act is like sticking your head in the sand.”

The Sandra Bland Act was a failure of communication and of unity, said Brandon Rottinghaus, a professor of political science at the University of Houston.

Rottinghaus added the 2017 state legislative session was more productive on criminal justice reform than the 2019 session.

“Some of the things that didn’t pass in 2019 that had some momentum were reforms of bail practices, which died in the Senate. There were other moves to limit arrests for nonjailable offenses like traffic violations,” Rottinghaus said.

But Rottinghaus said he expects to see Gov. Greg Abbott put some consensual items on the agenda to make policing more fair as well as addressing other criminal justice issues in prison and inmate care.

Ongoing responses to policing and criminal justice in the state’s largest cities may affect the Legislature’s work in spring 2021, Rottinghaus said.

“There’s often a trickle-up effect where local governments try to make reform efforts stick, and if they’re not fully successful they’ll pressure the Legislature to follow along,” he said. “ If enough local governments do that then you do see a cascade of movement towards codifying what many local governments are already doing, so I suspect that you would see movement in that direction.”

Additionally, Rottinghaus said he suspects local governments are acting first because they do not fully trust the Legislature or state-level officials to achieve the results they want.

There has been a tremendous limit to what local governments can do on a range of issues to act on their own without waiting for or allowing the state to step in to set rules, he added.

“Measuring change is extremely difficult,” Lambert said. “There is a conversation that has continued, and that’s massive because 25 years ago there would have been whispers at best. The problem is that the fuel to that conversation has tended to be more dead bodies. We are reactive instead of proactive.”

Additional reporting by Ben Thompson.