The department has held a series of forums and events all month long to raise awareness on a myriad of topics, like children’s mental health, trauma’s impact on brain development and compassion fatigue.

Fort Bend County is one of ten sites in the state of Texas to receive the Texas Change in Mind Learning Collaborative grant to develop a shared knowledge of brain science and race equity, said Connie Almeida, licensed psychologist and director of the county’s behavioral health services department.

The grant is presented by strategic action network, Alliance for Strong Families and Communities, which is made up of direct service organizations such as private, human-serving nonprofits; state associations such as regional federations or councils; and affiliate members like higher education institutions.

According to Alliance's website, the process of embedding brain science principles into Fort Bend County’s work will lead to improved outcomes for children and families and enhance organizational culture and leadership to build better systems and policies.

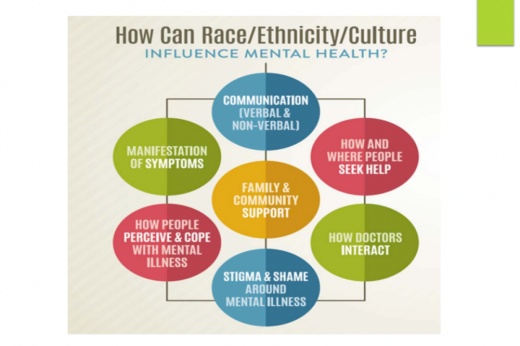

During the presentation, Almeida and Salem Kebede, a licensed mental health clinician with over ten years of experience, addressed the stigma associated with receiving mental health treatment within certain groups; culture, race, ethnicity and identity; and the importance of cultural competence and humility as physicians relate to clients and in peer-to-peer interactions.

Kebede said all of these are significant to a person’s psychological wellbeing, the level of care and treatment outcomes for clients, and the credibility of providers.

“Culture, race and ethnicity is a dynamic force that often informs a client’s response to treatment and the outcome of the treatment, the level of engagement and how they interpret their experiences, what they are and what they are not willing to expose when it comes to mental health treatment,” Kebede said.

Kebede differentiated between race, ethnicity and culture in her presentation. For example, Latinx is defined by the Census Bureau as an ethnic identity, she said, and can belong to a number of races.

In explaining the relevancy of racial designation in terms of mental health, Kebede said it can have “a tremendous social significance regarding behavioral health services, social opportunities, status and wealth.”

To show how cultural identity and geographic location both play a role in mental health and also how it constantly evolves, Kebede referenced her own upbringing in East Africa, where there was a “more conservative lifestyle” with mental health “seen as a weakness.”

Kebede said she went through a shift when she transitioned to the United States, and has been exposed to different cultures and perspectives in her professional experience. So much so, that her original worldview has changed, she said.

“We won’t be able to see things from the client’s perspective unless we have a good idea of where they come from and their experiences,” Kebede said.

Other elements that Kebede said should influence mental health treatment are the culturally-defined concepts and attitudes toward family and kinship, gender roles, socioeconomic status, education and substance use.

“Culture is a little bit of what makes us who we are,” Kebede said. “Having that understanding and being open to see people for who they are will help us tackle the mental stigma. How can we expect people to come out about their mental illness when we are not willing to see them for who they are?”

For physicians to develop cultural humility, Almeida said it involves the exploration of one’s personal histories of prejudice, cultural stereotyping and discrimination, understanding the trust and power dynamics between client and provider, and acknowledging that sameness and familiarity do not equal competence.

“To be culturally competent means to understand the history of oppression experienced by marginalized groups in society,” Almeida said. “That is difficult. It means you have to be comfortable in having those discussions, which are often uncomfortable.”

For organizations like Fort Bend’s Behavioral Health department to apply cultural competence, Almeida said it is a constant, unending process.

“It's engaging staff in these conversations around equity, diversity and inclusion,” the department’s director said. “For years we thought diversity was just that our workforce is representative of different races and ethnicities, but it's more than that. It's about making sure that we understand what our differences are and making sure everyone feels included in the organization.”