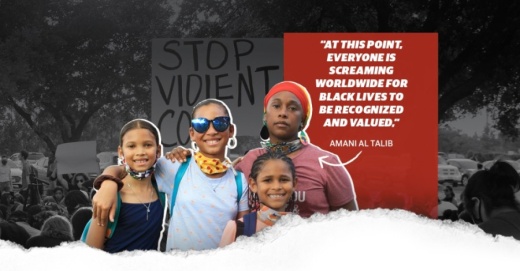

She came with her three daughters and said she is worried for her 21-year-old son enrolled in college in California. The coronavirus pandemic has amplified tensions, and the masks worn to prevent the coronavirus from spreading make it easier to judge people by only skin color and size, she said.

“They just see his skin color and his height ... and he can fit any profile,” Al Talib said.

Coordinated by three Katy ISD students Erika Alvarez, Foyin Dosunmu and Jeffrey Jin, the Katy for Black Lives Matter Protest was one among a series of rallies and marches occurring across the U.S. protesting police brutality and racial inequality following the death of George Floyd, a Houstonian who was killed while in the custody of the Minneapolis Police Department on May 25.

“At this point, everyone is screaming worldwide for black lives to be recognized and valued,” Al Talib said.

Another rally to bring awareness to local racial issues was held June 12 at Fulshear High School.

“What happened to George Floyd has opened a dialogue,” rally co-organizer Rhonda Kuykendall said. “People believe we don’t have these issues [in Fulshear and Katy], but we do.”

‘They are hurting’

Errol Clay—who owns Clay’s Mortuary & Cremations in the Katy-Brookshire area and is the pastor of Flavor Church in the Katy-Richmond area—said some have declined his funeral services once they learn he is African American.

“When people see me, sometimes they automatically put me in a category,” he said. “I’m a businessman, I’m a father and a pastor, and there’s still people that look at me like I’m trash. I’ve been harassed by the police before. I’ve had guns put on me before.”

Cmdr. Paul Follis, who lives in Katy and is a member of the Houston Police Department, attended the June 2 downtown Houston demonstration where thousands came to honor Floyd.

“Some were very derogatory to the police, and we understand that,” Follis said. “I don’t think any of us were offended by that. We understand that they are hurting ... from years of police violence.”

Gil Gray moved to the Katy area about 35 years ago because he wanted better educational opportunities for his son. He said nearly every time he walks into a store, people cower and look at his hands.

“There is an overriding guilt that comes toward you, and you can see it in the looks and the stares,” he said. “People are always watching you to see if you’re going to do something wrong. There’s this gigantic assumption of guilt.”

Katy protest attendee R.C. Simmons, a veteran and executive director of Katy-area nonprofit Jamsteld West Inc. and former Katy ISD board of trustees candidate, said he was called derogatory names while campaigning, but it no longer bothers him.

“I’ve been called [derogatory names] my whole life,” he said. “What bothered me was the fact that my daughter was approached, and the fact that my daughter felt uncomfortable. Being a single father, my first priority is to protect my children.”

Gray, Clay, Simmons and Al Talib said these racial tensions they experience is nothing new and is not exclusive to Katy, Houston, Texas, or the U.S. They also stressed that saying “black lives matter” does not mean that white lives do not matter. The statement reflects the need for equality for all.

"They're traumatized, and they feel like they're trapped, and they're unheard," Clay said. “When society says ‘white is right,’ it makes it seem like black is subpar. That’s why some people feel the need to maybe wear their hair a certain kind of way because they want to land that corporate job. ... they feel that pressure.”

‘Showing them love’

Simmons said the community needs leadership to move forward, and one way to do that is at the polls.

“During the school board election, the biggest complaint that I heard from people of color in the Katy community was, ‘They don’t care about people on the north side; they don’t listen to us,’” Simmons said. “And my response to that was, ‘Did you vote in the school board election? Did you give someone a reason to hear you?’”

Clay said finding the commonalities—such as parenthood, sports and educational opportunities—among diverse people is one way the Katy community could move forward. Empathy and understanding can help the healing process, he added.

Katy protest attendee Kamal Osman, who owns Houston55 Barber Studio in Katy, offers free haircuts to children who are less fortunate and the homeless through his nonprofit, Kamal’s Grooming Foundation.

“[We are] talking to the [children] and making sure they have someone in their corner that’s showing them love because that’s the first thing that’s going to break down that wall,” Osman said. “I’ve definitely experienced some issues, but ... I can’t let those issues get the best of me and tear down everything that I’ve done to this point and still trying to build.”

Meanwhile, Fort Bend County residents debuted a virtual art gallery called #ArtForJustice as a way to express hope in and engage with the national conversation about racial issues during the coronavirus pandemic.

The Fulshear Police Department meets once a quarter with local pastors of all colors and creeds to discuss issues that affect the community, Chief Kenny Seymour said. A group of about 60-70 officers and pastors met June 8— the day of Floyd’s public visitation in Houston—to pray for peace, strength and unity across the U.S.

“They know the heartbeat of the community,” Seymour said. Seymour said of the local church leadership. “There are a lot of conservations, a lot of issues at the table like the coronavirus and George Floyd. We feel that we need prayer and understanding.”

Al Talib said she believes the community cannot move forward until laws are changed to ensure equality.

“Don’t tell me my life matters; show me my life matters,” she said. “Put it on the books; put it in the laws. I want to see change. I want my children to see it, and I want my grandchildren to see it.”