“It was bad,” he said. “The water had drained out of the home, but everything was wet. ... It smelled like sewage. I could see mold growing.”

He estimated his home took on about 8 inches of contaminated water, and he spent thousands in repairs.

Although his home is not in a flood zone, it is in the Barker Reservoir’s flood pool, an area of land that stores stormwater during major rain events, he said. Soares said he did not know his property was in this flood pool when he purchased it in 2001.

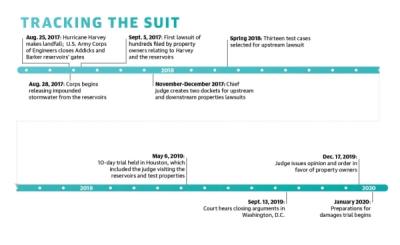

He joined a lawsuit alleging the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Galveston District unlawfully flooded 10,000 private properties upstream of the Addicks and Barker reservoirs in the days after Hurricane Harvey. A separate lawsuit was filed for properties downstream of the reservoirs.

After a 10-day trial, Senior Judge Charles Lettow of the U.S. Court of Federal Claims issued an opinion and order Dec. 17, concluding the Corps’ actions are liable and the upstream property owners are eligible to receive compensation. However, the downstream lawsuit was dismissed in its entirety Feb. 18 by Senior Judge Loren A. Smith of the U.S. Court of Federal Claims.

The upstream lawsuit will continue with another trial in November to determine damages, according to the team of lawyers representing the flooded property owners. The total financial outcome for property owners could be $1 billion to $5 billion, and the thousands of upstream property owners have until August 2023 to join the lawsuit.

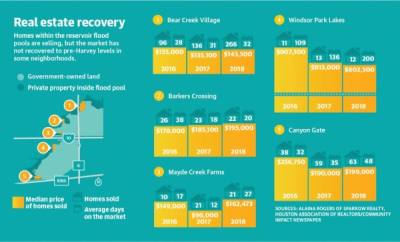

As these property owners wait for compensation, the residential real estate market is rebounding, local Realtors said.

“There are people who won’t ever buy in these neighborhoods because of the flooding,” said Tim Sojka, a local Realtor with See Tim Sell Property Group. “But they’ve recovered much better than I expected.”

The arguments

The Barker and Addicks reservoirs were built in the 1940s to help prevent the flooding of downtown Houston. During Hurricane Harvey, the Corps closed the reservoirs’ gates to impound water within the dam as instructed by 2012 operational guidelines, Lettow wrote.

The reservoirs captured about 140 billion gallons of water from the storm, according to previous Community Impact Newspaper reporting. The Corps began releasing impounded water Aug. 28, 2017.

“These dams are actually designed to do exactly what they did during Harvey,” said attorney Charles Irvine, part of the team representing the property owners. “Every time it rains, these dams impound water; the [Corps] close the gates [so] the water doesn’t flow downstream and flood downtown Houston.”

The Corps’ operations prevented about $7 billion in projected losses in downtown Houston, Lettow wrote. However, by impounding the stormwater behind the reservoir gates, the Corp’s operations flooded private properties upstream.

The lawsuit used 13 test properties, including Soares’, to represent the thousands of upstream properties that flooded to determine whether the government took private property without just compensation, violating the Fifth Amendment of U.S. Constitution, when operating the Addicks and Barker reservoirs during Hurricane Harvey to impound stormwater, Irvine said.

Community Impact Newspaper reached out to the U.S. Department of Justice, but it declined to comment.

One of the arguments Irvine team used was the government did not purchase enough property to store 100% of what is called the maximum design flood pool—or the maximum amount of water that may need to be stored on government-owned land during a major rain event.

Lettow decided the government unlawfully took the private property because it knowingly did not purchase enough property to store impounded water and has no plan to change the operation of the reservoirs.

The result

The government did not purchase the entirety of the maximum design pool because the Corps cannot afford to pursue projects designed to the worst-case scenarios, Lettow wrote of the defense’s argument.

And as the Greater Houston area grew westward, private developers began building on land within the reservoirs’ flood pool that was not owned by the Corps, Irvine said.

Local governments oversee development regulations in the Katy area. Harris and Fort Bend county officials previously told Community Impact Newspaper that they cannot outright prohibit building on private property.

Lettow’s opinion said Harris and Fort Bend counties knew subdivisions were being constructed within the maximum design flood pool of the Barker Reservoir but did not do enough to inform property owners.

“It is undisputed that [the property owners] did not know their properties were located within the reservoirs and subject to attendant government-induced flooding,” he wrote.

However, receiving compensation will not come immediately, Irvine said. The second phase of the lawsuit to determine damages has just begun. And once the judge issues another opinion and order, the government will likely appeal the judge’s decisions.

Irvine said he could not provide any timeline for when property owners could receive compensation; there are too many uncontrollable factors.

Irvine said he and his team plan to file a class-action lawsuit so the 10,000 owners of the upstream properties flooded by the reservoirs can opt in and receive compensation.

The effect

Even if the upstream property owners are compensated, they could be flooded again, Soares said. He wants a permanent solution to mitigate flooding and improve drainage on the eastern side of the Katy area.

“It’s nice to be reimbursed, but it doesn’t fix the situation,” he said. “What if another Harvey happens?”

The Corps is conducting a $6 million study to research and recommend projects for federal funding to address the flooding risk along Buffalo Bayou, which includes the reservoirs. This study will not be complete until October 2021, per a May presentation. Any projects presented cannot begin until Congress appropriates funds, which could take years.

Regional solutions to mitigate flooding upstream of the reservoirs include constructing a flood tunnel, containing the Cypress Creek watershed and building additional detention and retention ponds, said Wendy Duncan, a Willow Fork Drainage District director, the co-founder of Barker Flood Prevention Advocacy Group and a candidate for the Fort Bend County Precinct 3 commissioner Republican primary.

Harris and Fort Bend counties are working on home buyout programs with federal grants. Although it may be the easiest and least expensive solution for the properties that are upstream and downstream of the reservoirs, Duncan said home buyouts in these areas should be used sparingly.

“Think about how many people [we’d be] displacing all at one time and what that will do to our real estate market,” Duncan said. “Can we find homes with that many people all at one time? And what does that do to the taxing base?”

Brad Evans, a local Realtor with the Houston Properties Team, said a government buyout should only be considered if homes have been flooded multiple times.

“There’s real appreciation in [the residential real estate area upstream of the reservoirs],” he said. “It’s just a matter of time. ... Time to let the market take its course.”

Existing property owners who want to sell their property now—such as Soares, who moved out of state for a job opportunity and placed his home on the market in late 2019—must disclose the parcel is located within the flood pool due to a new law, Senate Bill 339, which became effective Sept. 1, Irvine said.

At a Jan. 12 community meeting held by Irvine and his team, many property owners in attendance expressed concerns that this new law will make it difficult to sell their property.

However, Evans and Sojka said neighborhoods located within the upstream flood pool of the reservoirs are recovering from the 2017 storm.

For example, in Canyon Gate the number of homes sold increased from 38 homes in 2016 to 59 homes in 2017 and to 63 homes in 2018, according to Houston Association of Realtors data. And in Mayde Creek Farms, the number of homes sold in 2016 was 10, which increased to 21 homes in 2017 and another 21 homes sold in 2018.

However, it is taking longer to sell homes, and home prices have not recovered in every neighborhood upstream of the reservoirs. In Canyon Gate, the median price of homes sold in 2018 was $199,000, about $58,000 less than the 2016 price of $256,750. But in Mayde Creek Farms, the median price of homes sold has increased from $149,000 in 2016 to $162,473 in 2018.

“There are challenges to selling these homes, but they’re still selling,” Sojka said. “And the further we move away from Harvey, the less important it will be to live away from the reservoirs. We have short memories.”