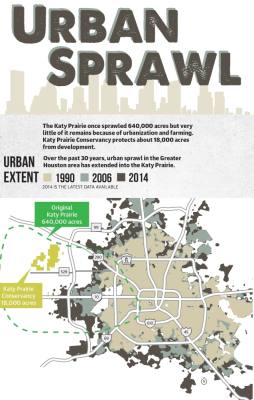

Long before the railroad and rice farming, the Katy area was filled with grass, prairie mounds, wetlands and wildlife as part of the 1,000-square-mile Katy Prairie.

The land’s flatness and ability to hold water originally attracted rice farmers to the area—and eventually subdivisions, shopping centers and offices followed—said Mary Anne Piacentini, the president and CEO of Katy Prairie Conservancy, a nonprofit land trust working to protect and restore the Katy Prairie.

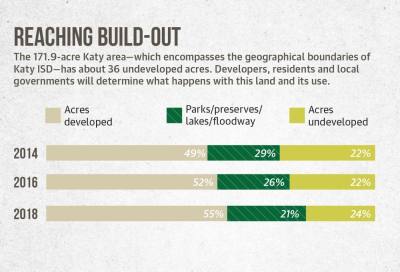

Today, 36 out of 172 acres in the Katy area are undeveloped, according to demographics firm Population and Survey Analysts. These acres are mostly west of the Grand Parkway and north of I-10.

“[Development] is a double-edged sword,” said Katy-area resident Lori Doucet-Alexander, noting the convenience of dining, shopping and entertainment options near her Nottingham Country home.

“But it’s been so much growth so quickly,” she said. “To widen the streets near my neighborhood, they want to cut down 50- and 60-year-old trees. ... If you don’t preserve, you lose it forever.”

Development growth is inevitable, but there are ways to balance development and conserve the Katy Prairie, said Piacentini and John Jacob, a geoscientist who recently retired as the executive director of Texas Community Watershed Partners, a program of Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service.

“We’re not going to stop the development,” Jacob said. “But we can build in such a way that is more friendly to the Katy Prairie.”

Ecological benefits

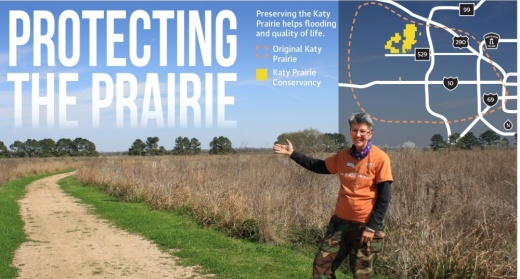

Since 1992, the KPC has urged stakeholders to conserve the historic Katy Prairie to help improve quality of life and flood mitigation, among other benefits, Piacentini said.

Prairie wetlands provide a filtering process to clean polluted runoff water, minimizing the need for stormwater detention and conveyance facilities, Jacob said. Prairie grasses also have deep root systems that hold and slowly release stormwater.

Nonprofit Houston Advanced Research Center estimates development has destroyed about 80,000 acres of freshwater wetlands in the Greater Houston area between 1996 and 2015.

The loss of 25,000 acres of wetlands is about a $650 million loss in stormwater detention, per a 2010 TWCP study.

And if the Katy Prairie is destroyed, some wildlife will go extinct, Doucet-Alexander said.

“Migratory birds need a specific place, with a specific type of grass and environment,” she said. “There is nowhere else for them to go [if the prairie is gone.]”

Over 27 years, KPC has acquired about 18,000 acres to protect, roughly 3% of the original size of the prairie, Piacentini said. KPC’s goal is to preserve at least 30,000 contiguous acres of the Katy Prairie, but increasing land prices are making it harder to acquire and protect these lands. “The Katy Prairie is part of a coastal prairie that actually stretched for 9.5 million acres along the coast of Texas and coast of Louisiana,” she said. “Less than 1% is left in its pristine condition and about 15-20% in a restorable condition.”

Building on the prairie

The KPC has no regulatory jurisdiction. Local governments, such as city and counties, set drainage and open-space regulations, but they cannot outright prohibit private owners from building on their land if they meet the platting and other requirements, Katy City Administrator Byron Hebert said.

“But every opportunity that we have, even if it’s not in the city of Katy, we’re going to ask the developers to go get involved and to understand,” he said. “All we can have is a conversation [with developers] that says, ‘Go be good stewards, do the right thing, and where you can, let nature be nature.’”

The Greater Houston area is newer to conservation then other parts of the country, Piacentini and Jacob said. The region grew quickly, and community leaders did always think of the consequences of paving the prairie.

“When you see what [the KPC has] preserved compared to what was there—it’s gone in a blink of an eye,” Doucet-Alexander said.

The conservation of wetlands is a long-debated subject at the federal level, and not all wetlands are protected, according to HARC. However, the federal government established a “no-net-loss” standard in 1989 to try to prevent additional wetlands loss, said Rick Howard, a project manager and ecologist with SWCA Environmental Consultants.

Under this policy, whenever wetlands are destroyed in a project, new wetlands must be created within the same watershed to replace them.

Developers in the Katy Prairie can build to preserve the land’s ecological benefits while increasing revenue, Piacentini and Jacob said.

Numerous studies have found that open spaces and parks increase property values, they said. A 2007 study published in scientific journal Managing Leisure found properties abutting or fronting a park see an increase of about 20% in property value.

Jacob said partner organizations of the TCWP crafted a 640-acre land-use plan specific to the Katy Prairie, incorporating high-density, low-impact development practices while preserving 480 acres of farmland and habitat.

“This pattern [of high-density development next to nature] is not foreign to us,” Jacob said.

Balancing development

PASA’s reports on the Katy area’s undeveloped land have noted the difficulties developers will have building in the prairie, its wetlands and the 100- and 500-year flood plains.

“Every site comes with its own challenges, whether it’s prairie or forest,” said Heath Melton, the executive vice president of master-planned communities at the Howard Hughes Corp., which is building Bridgeland, which neighbors KPC’s lands.

Bridgeland reserved about 28% of its 11,400 acres for green space with parks, lakes, natural creeks and restored native habitat, he said.

Another master-planned community that has incorporated aspects of the prairie is Cross Creek Ranch near Fulshear, Piacentini said. Flewellen Creek—which runs through the property—was restored with tall grasses and trails, Cross Creek General Manager Rob Bamford said.

The city of Katy is also creating a nature preserve within the 169-acre, mixed-use development Katy Boardwalk District. A 90-acre lake will have rice paddies, prairie grasses and wetlands to attract wildlife, said Kayce Reina, the city of Katy’s director of tourism, marketing and public relations.

“Everyone is aware of the environment, particularly our buyers,” Bamford said. “There’s a high level of awareness to our climate and environment.”

Doucet-Alexander said she hopes more developers will realize the benefits of conserving and restoring the Katy Prairie.

“You can’t ask them not to develop—their job is to look for those opportunities,” Doucet-Alexander said, “[But we need to] give those that are trying to conserve [the Katy Prairie] an equitable seat at the table when those conversations are happening.”