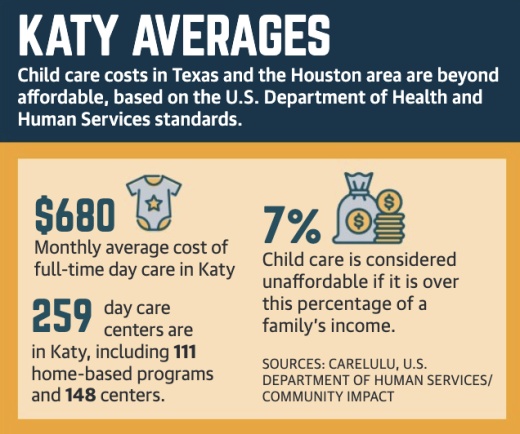

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, child care is considered unaffordable if it requires over 7% of a family’s income. As of October 2020, the typical Texas family was paying 15.7% of its income for infant care for one child, according to the Economic Policy Institute. By this standard, 15.8% of families could afford infant care.

While child care is an important service for working parents, it can be costly due to state staffing requirements, local child care and early education center officials said.

At Vanguard Academy, an early education center serving Katy since November 2020, owner Hao Wu cited necessary increases to teacher salaries as a catalyst for the increased price of tuition from $200 per week to $215 per week in April.

“We have to increase the teacher salary because after the pandemic, inflation [caused] all the costs [to go] high,” Wu said. “We have to increase teacher salaries if we want to keep that teacher here.”

Both Harris and Fort Bend counties have made recent efforts to alleviate child care costs.

Fort Bend County closed applications for its Child Care Voucher Program on Aug. 18. The project, designed and launched in early 2021, administered $2.4 million to more than 1,200 low- to moderate-income families across the county who were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

On June 14, the Harris County Commissioners Court approved the use of $48 million in American Rescue Plan Act funds for a new child care and early childhood development program that aims to increase the accessibility of child care in Harris County by 10%.

The three-year pilot program is designed to create more child care options for children age 3 and younger in Harris County communities. It is also designed to provide funding to child care workers for better wages and to child care centers to recover from pandemic-induced hardships.

Increasing costs

Brightwheel, a child care management software company, reported the average price of child care in the Houston region is $1,087 monthly, an 8% average increase from 2021.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ consumer price index—a measure of the average change in prices—the cost for day care and preschool rose 3.2% nationally from May 2021 to May 2022.

While parents are spending more on child care than they were two years ago, child care centers in Katy face a unique challenge due to the city’s continued development and Katy ISD’s draw for young families, officials said.

Lou Ann McLaughlin, who has served Katy for 23 years with five Primrose preschools and infant care centers, said she had to reduce the playground size for two of her early education centers because of the price of land.

"To put a child care site [in Katy] is more expensive,” she said. “Because of the land cost, we couldn’t get quite as much land for the [sites] we built at West Cinco [Ranch]. It is getting more expensive for sure, as is everything.”

Child care centers are required to have a minimum of 30 square feet per child, per Texas Health and Human Services Commission regulations. This means a facility aiming to hold 100 children would require at least 3,000 square feet—excluding office space, entryways and playgrounds.

Paul Ahren, who opened a Kids R Kids Seven Lakes facility in south Katy in 2021 and previously directed a Kids R Kids child care center from 2004-17 in north Katy, said inflation has increased the annual tuition for his child care center higher than average.

“Normally, another five bucks a year would cover inflation, but we did a little bit steeper [increase] this time because of the cost of gasoline and food,” he said.

Staffing challenges

Child care officials in Katy said they face challenges in recruitment and retention and struggle to pay staff a livable wage.

Ahren said he does not employ enough teachers to support the full capacity of his facility and that good teachers are harder to come by.

“We are barely at a break even; [we have] about 200 kids, and we are licensed for 360,” he said. “We want to be above ratio so that we can do more activities in the room and not just be managing kids.”

For Ahren, teacher pay is higher than it was five years ago and more difficult to maintain. Despite recruitment efforts, securing staff has been hard.

“A lot of people are looking for a lot more money than the child care business can really produce,” Ahren said.

A September 2021 National Association for the Education of Young Children survey reported 86% of child care centers in Texas saw staffing shortages; 79% of those surveyed identified wages as the main recruitment challenge.

Meanwhile, in May 2021, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported the average annual wage for a child care worker in the Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land metropolitan area was $24,150—the ninth lowest-paying occupation out of the 709 occupations in the region that receive an annual wage.

Wu said inflation has made it harder to pay his staff a livable wage, which makes retention much more challenging. Retention is particularly important to parents who want to build a rapport with the professionals caring for their children and to provide children with stability, he said.

“On the parents’ side, they are looking for the centers [with] those teachers that have been there for years,” Wu said. “They don’t want to see that teacher change very often. So that is a big challenge for us.”

Resources and funding

In August, Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo—alongside Precinct 1 Commissioner Rodney Ellis and several members of Congress—announced the $84 million Brighter Futures for Harris County Kids program, which encompasses several early education and child care initiatives.

“This is a historic investment. Never before has Harris County had this focus on children,” Hidalgo said in a news release. “Each component of the Brighter Futures for Harris County Kids initiative demonstrates that local government can improve the lives of residents for the long term when working with partners, community members, parents, teachers, and caretakers.”

One portion of the three-part package includes the $48 million Child Care Contracted Slots program, which aims to create up to 1,000 child care slots for children age 3 and younger with an emphasis on communities where there are few to no such options.

The slots program also aids child care centers in financial recovery and stabilization following the exacerbating effects of the pandemic while supporting ongoing capacity building for child care providers and requiring participating organizations to pay staff at least $15 hourly wages.

Meanwhile, in Fort Bend County, the Child Care Voucher Program issued just under 75 vouchers to Katy applicants, almost 300 to Rosenberg applicants and almost 225 to Richmond applicants, said Qaisar Imam, program administrator for the county’s voucher program.

“Lot[s] of parents were returning to the workforce after the pandemic and could not afford child care due to reduced income levels,” Imam said.

Area child care providers, such as Ahren, hope to foster relationships with KISD and local developers to work in tandem and not in competition with one another.

“Our goal is to work directly with the ISDs and say, ‘Look, we have a prekindergarten facility, so you don’t need to build another campus,’” he said.

Ally Bolender contributed to this report.