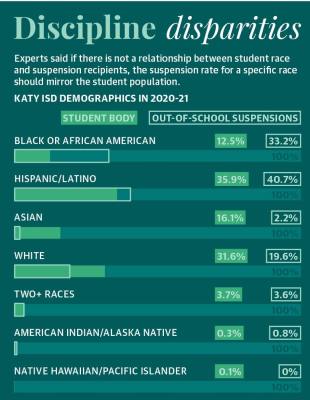

Statewide and nationwide, experts said Black students are being disciplined at rates disproportionate to their representation in the student population. For years, Katy ISD has been no exception: While about 12% of the district’s student population was Black, these students received about 33% of all out-of-school suspensions in the 2020-21 school year, according to KISD data from a Community Impact Newspaper public information request.

Experts such as Vicky Sullivan, a senior staff attorney with the Education Justice Project at Texas Appleseed, an Austin-based social, economic and racial justice nonprofit, said the organization has long advocated for discipline reform around these issues.

“One of the things that I think we’re dealing with in public education is that there is an urgent need to transform how we see school discipline—one that acknowledges and confronts the ingrained inequities and systemic barriers that result in further marginalizing some students,” Sullivan said. “How we achieve that—that’s the million-dollar question.”

With many variables affecting discipline rates, including factors like socioeconomics, language barriers and mental health, KISD has taken steps to address the disparities, district spokesperson Maria DiPetta said via email.

“Continuously examining Katy ISD’s student data, providing ongoing training to our staff and implementing student support systems with the goal of ensuring that the school experience is a positive and supportive one for every child, is a priority that is embedded within our practices,” DiPetta wrote.

Extent of inequality

Since 2015, Black students have represented roughly a 10th of the district's student population but have continued to be disciplined at higher rates, consistently receiving between 29%-35% of all out-of-school suspensions in the district each year.

Additionally, Hispanic students which made up 36% of the district—made up 41% of the district’s out-of-school suspensions.

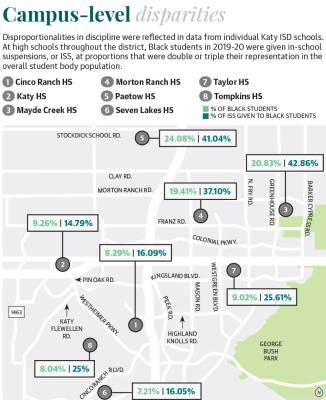

These disparities were reflected in the Texas Education Agency’s data for individual KISD high schools as well, with Taylor and Tompkins high schools having some of the highest disparities. In 2019-20, about 9% and 8% of the students at these schools, respectively, were Black, but Black students received about 25% of the in-school-suspensions at both campuses—almost triple their representation in the overall student population. Mayde Creek and Seven Lakes high schools also had higher levels of discipline disparities.

Horace Duffy, a research specialist at Houston ISD with a doctorate in sociology focused on student discipline, said race is a factor in how likely a student is to be suspended.

“We know that there’s a racial bias and that Black and Latino students are not inherently more deviant than white and Asian students. The research bears that out,” Duffy said. “These are pretty big disparities. I just can’t emphasize enough, ... they’re not Katy specific.”

Racial disparities in discipline data can be found in nearly every school district in Texas, Sullivan said. In the 2019-20 school year, Black students in Texas made up 13% of all students but 31% of out-of-school suspensions, according to TEA data. A November 2020 report from The Education Trust, a national education advocacy group, showed Black students are five times more likely to receive out-of-school suspensions compared to their white peers.

“Texas specifically has struggled with that historically,” said Ashton Millet, an organizer with Organizing Network for Education Houston. “It’s a trend you see across the state, and it’s definitely a trend you see across the Houston area.”

Contributing factors

Education experts said the causes for racial inequities in discipline vary but stem from structural racism in state and local school rules, in addition to unconscious biases from teachers and administrators.

“All of us have and carry our biases, and implicit bias 100% shows up within the classroom,” Millet said. “When teachers have discretion to write kids up or discretion to decide what rules they’ll enforce versus others, a lot of times their implicit bias comes out.”

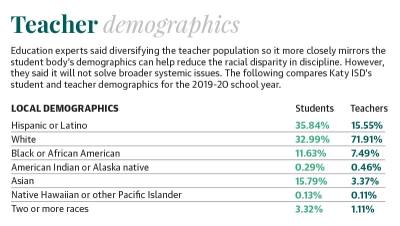

TEA data shows in 2019-20, 71.91% of teachers in KISD were white while 7.49% were Black and 15.55% were Hispanic. Meanwhile, 32.99% of students were white; 11.63% were Black; and 35.84% were Hispanic.

Experts said discipline in schools is often discretionary. Chelsea Torres, a 2012 graduate from KISD’s Taylor High School, said she felt like some teachers disciplined more harshly than others, and discipline methods often did not correlate with the behavior.

“Punishments were definitely left up to the discretion of the teacher,” Torres said. “I was one of the best students in my class, and there were times where I feel I was punished unfairly for my behavior.”

KISD officials declined to comment on why specific high schools have higher discrepancies in their discipline data.

Structural causes for racial inequities in disciplinary practices occur when the violations listed in codes of conduct target students from a certain ethnic or racial group, said Virginia Snodgrass Rangel, an assistant professor in the department of educational leadership and policy studies at the University of Houston.

According to TEA data, the most common reason for a KISD student to have been disciplined in 2019-20 was for a violation of the local code of conduct with 5,278 of these incidents being reported that year. The next highest violation category was fighting at 643 reported incidents.

Distinct from other infractions such as alcohol, controlled substances or felonies, violating a local code of conduct is a broad category that can vary by school and district, Snodgrass Rangel said.

“This could be things like boys having long hair, your pants are sagging, not wearing a belt, your nails are too long,” she said. “Oftentimes these codes of conduct, purposely or not, will essentially make it much more likely that kids of color—Black kids in particular—are the ones who are targeted for these sorts of discretionary violations.”

KISD officials said the district’s discipline management plan, as well as its student code of conduct, are reviewed annually by the Katy Improvement Council, an advisory committee consisting of parents, teachers, campus and department administrators, and legal counsel. Addressing disparities

To begin addressing racial disparities in schools, Snodgrass Rangel said districts should reduce the number of kids who are being suspended and the racial disparity in suspensions given.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, which led to learning loss among a wide cross-section of students, a 2021 report from Texas Appleseed calls for banning disciplinary practices—such as suspensions and expulsions—that remove students from the classroom learning environment.

Additionally, Sullivan said she advocates for educators receiving training on more effective behavior management practices.

“The only tools administrators often have in their toolbox consists of exclusionary discipline tools,” Sullivan said. “If you only have a hammer in your toolbox, then you tend to see every problem as a nail. ... It is incumbent upon school leaders and administrators to develop a toolbox with positive behavioral strategies that are responsive, restorative, instructive and supportive to students.”

Millet said while the state Legislature has a role to play in allocating resources for solutions—districts and individual campuses also bear some responsibility.

“It’s up to the school districts to be leaders,” Millet said. “That’s when campuses and principals will feel the support to actually use their autonomy and their discretion to have an aligned vision of ending inequity around school discipline.”

According to DiPetta, KISD has responded by implementing programs that are proactive in addressing student needs.

“Katy ISD has multiple avenues for students to reach out for support and guidance,” DiPetta wrote. “These ongoing resources provide the district opportunities to support students and their families before the issue or concern results in a reactive or poor decision on campus that may lead to discipline action.”

In Fort Bend ISD, where similar disparity issues exist, district administrators said FBISD has begun implementing positive behavior intervention supports and restorative practices—two alternatives that utilize positive reinforcement and communication in lieu of punitive disciplinary measures.

In the 2019-20 school year, FBISD reported 478 reports of restorative practices. The district piloted this program in 2016-17 and is working to train teachers at every campus, said Deena Hill, the district’s executive director of student support services.

“We have good answers ... to address these issues; it just takes the resources and the will to make these changes,” Snodgrass Rangel said. “It is not easy, but I think our kids deserve it.”•