According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, an opioid is defined as a class of drugs that includes heroin; synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl; and prescription pain relievers, such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine and morphine.

Information from the Texas attorney general’s office indicates drug overdose deaths increased by around 32% in 2020 from the previous year, driven primarily by opioids. Additionally, provisional data from the National Center for Health Statistics showed opioid overdose deaths nearly doubled in Texas from January 2019 to January 2021, and there was a 30% increase in deaths from November 2020 to November 2021, the most recent data available.

“These are diseases of despair that we’re dealing with,” said Tyler Varisco, a health services researcher with the University of Houston. “When people are economically challenged or psychologically challenged as many of us have been over the past two years, we see increased vulnerability in our communities to opioid use and other forms of substance misuse.” With increased isolation and financial stresses, the pandemic further exacerbated struggles against the opioid epidemic in Texas. Recovery treatment transitioned into less effective online services, and access to quality treatment became more complicated, local experts said.

Opioid usage varies

In the late 1990s, pharmaceutical companies began marketing prescription opioid pain relievers as drugs that were not as addictive as previously thought, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. As a result, these drugs, which had formerly been prescribed only to treat acute pain, became the prescription of choice to treat chronic, long-term pain.

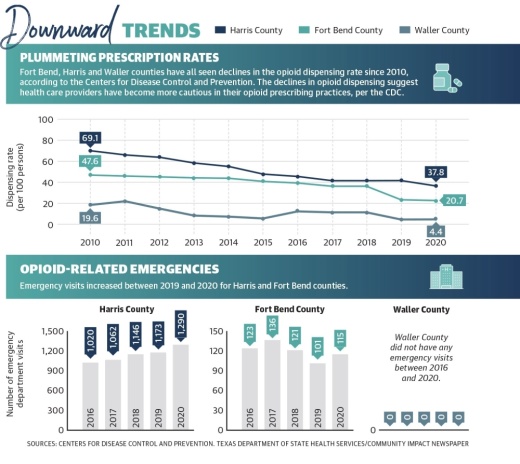

In 2020, a little more than 37 prescriptions were issued on average for every 100 residents in Harris County with about 20 prescriptions being issued for every 100 residents in Fort Bend County, based on the most recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. Waller County had an average of 4 prescriptions issued for every 100 residents.

The Fort Bend County Sheriff’s Office said via email while narcotic encounters, or instances in which officers encounter drugs, did decline during the pandemic, they are starting to rise again.

“Narcotic-related encounters within Fort Bend County dipped for a period of time during the height of the pandemic,” said Brad Whichard, special investigations division captain for the sheriff’s office. “While it can be surmised that decreased traffic in general attributed to the reduction, we are seeing encounters return to prepandemic levels.”

Reported opioid overdose deaths rose 25% from 2019 to 2020 in Texas, per the NCHS. James Langabeer, director of Houston Emergency Opioid Engagement System, the largest opioid treatment program in Harris County, said what happens to the body during an overdose can lead to death.

“Basically, opioids depresses your respiratory system to where you almost aren’t taking any breaths per minute,” Langabeer said.

According to the CDC, synthetic opioids, like fentanyl, have been one of the major driving forces in the rise of overdose deaths. One reason for this is fentanyl is unknowingly being put into other drugs, said Les McColgin, a liaison for sobering center Houston Recovery Center who was addicted to opioids and used them on and off for 35 years.

“To be honest with you, I was never scared of anything. It didn’t matter; I wanted it as strong as I could get it. [Fentanyl] scares me,” McColgin said.

Meanwhile, the number of reported opioid overdose calls the Katy Fire Department responds to within Katy’s city limits has risen since 2017, as has the percentage of those calls that resulted in an emergency room visit. Despite this increase, the KFD had only 38 opioid-related calls to service in 2021.

“I don’t believe it’s really been an issue for us,” said Dana Massey, assistant fire chief of emergency medical services for the KFD. “It’s kind of a joke around here that we live inside a bubble inside the city limits of Katy. I know right outside the city limits they’ve gone way up.”

Massey attributes the lack of calls to the city having mental health officers who help during and after an overdose crisis as well as residents’ fear of law enforcement as police officers also respond to suspected overdose calls.

“People are afraid to call for their loved ones in fear of law enforcement, so they throw them in the car and drive,” Massey said.

Pandemic effects on treatment

Varisco described several underlying causes of substance use disorders the pandemic has exacerbated, including patient access to treatment, increased financial stresses and isolation. Varisco said he believes the drastic changes to health care for individuals experiencing addiction undid recovery work performed for patients before the pandemic.

According to the Treatment Episode Data Set, which compiles national patient discharges from treatment for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, detoxification treatment discharges became less common from 2016-19, when detoxification discharges decreased from 20% of all discharges to 16%. However, the patient completion rate of detoxification treatment remained stable with fewer than half of patients completing treatment.

“When you have a destabilizing event like a global pandemic, [vulnerabilities in health structures] become more evident,” Varisco said.

With in-person treatment at risk due to the coronavirus, health care centers went remote in 2020. Many centers were limited to offering substance use disorder care through telehealth services as opposed to in-person and personal programs, complicating opioid recovery for patients.

Henry Holland, the public relations subcommittee chair for Houston Narcotics Anonymous, said the nonprofit adapted to pandemic restrictions by using Zoom and its phone line for meetings.

“The struggle came with the disconnect that you’d normally get with meeting a person in person versus meeting a person virtually,” Holland said. “It didn’t interrupt how we function; it didn’t interrupt the access to a meeting. It did not interrupt the ability for sponsors and sponsees to interact with one another.”

Additionally, at the beginning of the pandemic, Varisco said there was some confusion about what treatments were acceptable. A 2020 memo from Phil Wilson, the Texas Health and Human Services Commission executive commissioner, said buprenorphine could be prescribed virtually, but methadone required a face-to-face evaluation.

According to the SAMHSA, buprenorphine and methadone are FDA-approved drugs used in combination with counseling to treat opioid use disorders.

“I don’t know if [the policy] was well understood by providers, and that led to lapses in our treatment,” Varisco said.

Government solutions

State and county entities are working to address the opioid epidemic and the effects the pandemic had on recovery through local funding, law enforcement resources and increased education surrounding opioid misuse.

Many officials agree the use of Narcan, a nasal spray that can administer naloxone during suspected overdoses, is something that should be encouraged and used by emergency agencies. Langabeer did note there has been an increase in how many doses are having to be administered to someone who has overdosed.

“Instead [of] one [dose of Narcan], we are often seeing four and five of these given at the scene of an incident. That just speaks to how [opioids are] becoming so much more intense and potent,” he said.

Statewide, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton announced Feb. 16 that the state had secured a $1.17 billion settlement with three major pharmaceutical companies: AmerisourceBergen, McKesson and Cardinal. According to the attorney general, Texas has secured $1.89 billion to date from opioid settlements.

Additionally, 482 Texas municipalities signed on to two settlements with Janssen—owned by Johnson & Johnson—and with AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health and McKesson, according to the attorney general’s website.

According to documents from the attorney general’s office, the city of Katy will receive $52,467 in settlement funding, while Harris, Waller and Fort Bend counties will receive roughly $15 million, $126,206 and $1.5 million, respectively.

A list of funding uses provided by the attorney general’s office includes community drug disposal programs, training for first responders, and youth-focused programs that discourage or prevent misuse.

McColgin encouraged people to disregard any previous notions they might have about opioids.

“This idea that it’s only heroin addicts and hardcore drug addicts that are overdosing on this stuff has to be completely eliminated or else we miss the most vulnerable people,” he said.