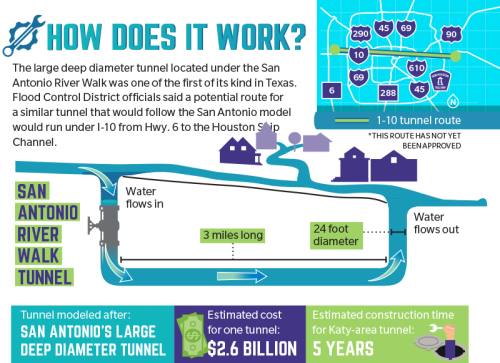

The Harris County Flood Control District is eyeing a new drainage tool that could significantly help with flood mitigation during major storm events. Officials from the district said they have identified nine routes for smaller tunnels throughout the Greater Houston area that could connect to one large deep diameter tunnel that would run 23.5 miles under I-10 from Hwy. 6 to the Houston Ship Channel.

Large deep diameter tunnels are not new drainage projects to the U.S.; they have been used in states like Ohio, South Carolina and in Texas at the San Antonio River Walk, according to HCFCD Chief Operations Officer Matthew Zeve.

“One is right underneath the San Antonio River Walk, and it was the first one of its kind in Texas,” Zeve said.

The purpose of the large deep diameter tunnels is to efficiently move large volumes of stormwater in the case of a major storm event, Zeve said. The tunnels cost billions of dollars and would take years to build, but they could significantly help with drainage throughout the region, he said.

Plans for preliminary and geotechnical engineering services to construct the I-10 tunnel were included on the list of HCFCD projects for the $2.5 billion bond voters decided on Aug. 25, but the district has already taken steps toward the project.

Harris County Commissioners Court approved the HCFCD’s request for a $400,000 grant application to the U.S. Economic Development Administration that will help fund a feasibility study of the tunnel. Zeve said he hopes to hear back from the EDA about approving the grant within the next month.

“We are fairly certain that because tunnels have been built in other places that have similar geology to Harris County, we feel like the feasibility study will come back with a positive answer,” Zeve said.

Zeve said the probability of the tunnel being constructed depends on the EDA’s decision to approve the grant for the feasibility study and the results of the bond election. Funding from the bond would be used to help fund additional geotechnical and preliminary engineering services for the tunnel and tunnel routes. Bond results could not be included as of press time.

‘An emergency outlet’

One area where the tunnel could help with flooding includes Katy. Zeve said smaller tunnels that connect to the main tunnel could provide a secondary outfall leading into the Barker and Addicks reservoirs.

“A large diameter deep tunnel could provide an emergency outlet for major, major storm events so that the reservoirs, when they fill up … they don’t fill up into the flood pool areas where there are homes,” Zeve said, referencing the homes near the Barker Reservoir that flooded during Hurricane Harvey.

Zeve stressed the project that was approved in the list of finalized projects for the $2.5 billion bond is not to construct any one tunnel, only to fund the investigation and preliminarily engineering services for several large diameter tunnels throughout the region. He estimated the one I-10 tunnel could cost upward of $2 billion.

The HCFCD is in discussions with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to secure hazard mitigation grant funding through a specific Section 406 program that would help fund the project, Zeve said.

“This [Hazard Mitigation Grant Section 406] is the program that funds the humongous projects,” Zeve said.

Zeve said while $2 billion for one tunnel may sound like a lot to residents, the damage Hurricane Harvey inflicted on the region was upward of $100 billion.

“Compared to Hurricane Harvey, the tunnels are actually cheap,” Zeve said. “It’s all about perspective.”

After a feasibility study is conducted, Zeve said the next step would be to conduct more preliminary engineering work and decide where the tunnels would connect to avoid areas where the district would have to obtain right of way.

“A lot of tunnels are built underneath major roadways because road right of way is public right of way,” Zeve said. “So that would be the next big effort is to figure out those routes.”

If the I-10 tunnel becomes a reality, Zeve said the project could take up to 15 years to complete depending on studies, funding and resources. The portion of the tunnel that would connect to the Barker and Addicks reservoirs could take up to five years, he said.

“The beauty of the tunnel construction is it’s actually minimally disruptive to the public, which means we don’t have to shut down roads, we don’t have to divert traffic, we don’t have a lot of noise,” Zeve said. “We don’t have all those things that people are used to seeing in big construction projects.”