As Fort Bend, Harris and Waller counties continue to recover from flooding brought about by Tropical Storm Harvey, their respective governing bodies are weighing options to mitigate flooding and meet modern drainage standards.

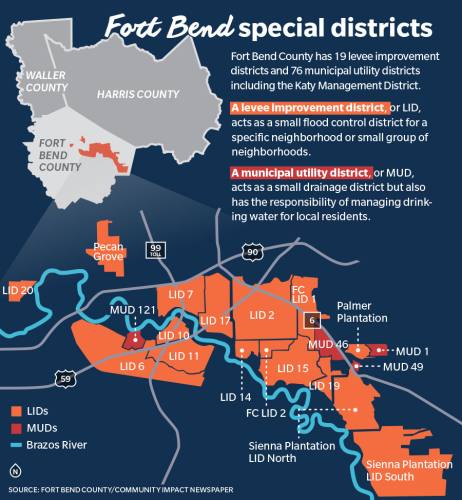

Fort Bend County officials are considering the creation of a flood control district, but that idea is in its infancy, according to the office of County Judge Robert Hebert. The county has a drainage district and 19 levee improvement districts, commonly referred to as LIDs, according to the county engineer’s website.

It also has several cities that handle their own water management as well as municipal utility districts, or MUDs, which help manage and improve drainage.

The cost of maintenance

Mark Vogler, chief engineer and general manager of the Fort Bend County Drainage District, explained that the difference between a drainage district and a flood control district is that the former maintains drainage and flood control assets that a county already has in place. A flood control district maintains those assets and can build new infrastructure to prevent flooding and improve drainage.

“Our annual [maintenance] budget for the county drainage channels we maintain is about $10 million,” Vogler said. “This includes bridges, water gates, vegetation control, pipes, swale ditches, desilting and erosion control among other things.”

Fort Bend County’s LID 19 has a budget of roughly $748,000, while LID 15 has a budget of more than $2.4 million. LID 19’s budget includes $140,000 for levee maintenance, while LID 15 sets aside $101,000 for maintenance and operation of the new Alcorn Bayou pumping station.

In contrast, the Harris County Flood Control District has an operating budget of $120 million, half of which is used for maintaining existing infrastructure and operations, with the other half going to improvements and new flood control infrastructure, said Karen Hastings, Harris County Flood Control District project communications manager. HCFCD’s budget for fiscal year 2017-18 includes $1 million for home buyouts to allow residents affected by flooding to move away from flood plains and $2.1 million for improvements to Berry Bayou near Pasadena.

Drainage district staffers are stretched thin as well, after dealing with two significant floods in as many years. The 2016 Tax Day Floods damaged about 22 miles of Willow Fork Bayou, causing erosion and bank sloughing—soil falling in clumps— Vogler said. The county was still working on that when Harvey hit.

“We’ve been working on repairing those and pretty much all over they’re re-sloughed now because of the high water and the quick drawdown on the river. So, we’ve got a lot of work to do,” Vogler said.

An oversight role

Fort Bend County’s LIDs, MUDs and cities can also make drainage improvements. The drainage district interacts with each of these in different ways, Vogler said. The drainage district helps the LIDs with their continuing education programs and inspects the levees maintained by each LID to ensure they are up to standards established by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Meanwhile, the MUDs are largely self-regulated and are more independent, although the drainage district will assist them with continuing education upon request. Some MUDs create and maintain levees, which must meet the same standards as those operated by an LID, Vogler said.

The drainage district also assists with planning by reviewing drainage designs for new development, according to the district’s website. The plans are reviewed by district staff and then submitted to the Commissioners Court for approval. This process prevents poorly planned developments from creating drainage hazards for current and future residents, he said.

Infrastructure codes outdated

Fort Bend County is capable of adding drainage measures, Vogler said. However, when it does, it usually must do so through a bond measure at the polls. Once approved, the proposed project is then implemented through a contractor rather than by the district doing the work.

Dependence on other entities to make improvements has the county relying on agricultural drainage standards from decades ago, Vogler said.

“The county’s drainage district was started up back in 1950 when [the county] was predominantly agricultural, and most of the ditches were built to an agricultural capacity, which is 3 inches in 24 hours on cropland, and 2 inches in 24 hours on pastureland,” he said.

According to Stephen Wilcox, a hydrology engineer with Costello Inc., a local engineering company that helps municipalities study and manage water drainage, the existing engineering standard for stormwater drainage is that it be able to handle 12.4 inches of water in a 24-hours.

However, Fort Bend County is not the only entity struggling with outdated drainage infrastructure. At a recent Katy City Council meeting, Costello presented findings of a study conducted on the water flow during the 2016 Tax Day Floods. During the presentation, engineers and city officials said much of the city’s drainage infrastructure was out of date. Some of the water management tools used standards from the 1980s, Wilcox said, but some may be as old as Katy itself, which was incorporated in 1945, according to the city’s website.

Now, Fort Bend County and the city of Katy are both considering options to improve drainage within their borders, according to officials. Katy Mayor Chuck Brawner is reaching out regularly to state and local legislators to push for a third reservoir northwest of the city to complement the Addicks and Barker reservoirs, he said. A possible flood control district within Fort Bend County would allow the county to improve drainage to meet modern standards, but these things take time.