“It creates a certain amount of confusion, a lack of consistency, and it feeds into this national debate that we’re having about the need for police reform,” said Kevin Lawrence, executive director of the Texas Municipal Police Association, a statewide police union.

Four current and former deputies in Rosen’s office, as well as a victims’ advocate previously employed by the office allege that a lieutenant and assistant chief hosted undercover “bachelor party”-style anti-human trafficking operations throughout 2019. In the lawsuit filed in May, deputies accuse the superiors of sexual harassment and assault during efforts that were described as “more of a party atmosphere than an actual operation.”

In a statement issued May 24, Rosen said he directed an internal investigation into the matter, which the lawsuit states was initiated in late 2020. Rosen said he did so despite never receiving a “formal complaint” and that the inquiry “found no violations of law or policy.” He went on further to state he has “a zero-tolerance stance against sexual assault and sexual harassment and would never allow a hostile work environment as alleged.”

As a result of the allegations, federal authorities launched an investigation into Rosen’s office, the plaintiffs’ attorney, Cordt Akers, confirmed with Community Impact Newspaper in July.

While the Precinct 1 lawsuit and investigation are recent developments, the questions surrounding the constables’ role in Harris County’s law enforcement ecosystem are nothing new, said Bill Fulton, the director of the Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research and co-author of an September 2018 study on the topic.

“There’s a lot of understandable criticism, but nobody’s got the motivation to invest the political capital required to reform the system,” he said.

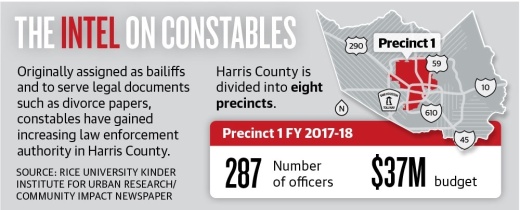

Proponents of the county’s eight constable’s offices, which employ over 1,500 deputies, said they provide much-needed support to the Houston Police Department and Harris County Sheriff’s Office while targeting community-specific needs.

“Over time, we’ve had a great number of people move into the county, and it’s been overwhelming for the county and the city police departments,” said Mike Knox, an at-large Houston City Council member and a former Houston police officer and investigator.

Critics, however, said a lack of uniform oversight across agencies in the state creates an environment where misconduct can go unaddressed and taxpayers fund duplicate services.

“Having this many agencies means there’s that many different ways you can have a lack of uniformity and a lack of consistency,” Lawrence said.

Range of duties

Originally tasked with serving as bailiffs and servers of legal documents such as divorce papers and eviction notices, constables have gained increasingly significant responsibilities, particularly in Harris County, the Kinder Institute study found.

Originally tasked with serving as bailiffs and servers of legal documents such as divorce papers and eviction notices, constables have gained increasingly significant responsibilities, particularly in Harris County, the Kinder Institute study found.Out of the state’s most populous counties, for example, Harris County is the only one that allows entities such as civic clubs and homeowners associations to pay the salaries of on-duty constable deputies to patrol their neighborhoods, the study found.

“In Harris County, for a variety of reasons, the constables have become this large additional police force. ... That is not the case basically anywhere else in Texas,” Fulton said.

As a result, Houston residents live within the jurisdiction of the Houston Police Department, the Harris County Sheriff’s Office and the Harris County Constable’s Office, which is split into eight precincts. Some also live within the boundaries of university, public transit and other small law enforcement entities.

Knox said the agencies support each other while serving unique duties within the county. HPD’s 5,400 officers, he said, are “covering 660 square miles with a population of 2.3 million people all calling the police for something.”

Oversight in question

Texas law is notably lax when it comes to the standards required to create a new law enforcement agency, Lawrence said. The total number of agencies in Texas has grown faster than elected officials can create uniform oversight and accountability measures.

Texas law is notably lax when it comes to the standards required to create a new law enforcement agency, Lawrence said. The total number of agencies in Texas has grown faster than elected officials can create uniform oversight and accountability measures.“Somehow, someway, we have to bring all these agencies into a world where they can in fact have some basic policies in common,” he said.

As of 2008, the most recent year data was collected, Texas had the highest number of total law enforcement agencies in the nation, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. At over 1,900 individual agencies, Texas far outpaced states with similar populations at the time, such as California and New York. Both had just over 500 agencies, according to the bureau.

The average number of officers per agency, however, is much lower in Texas, indicating the state has a larger number of small departments rather than a higher total number of officers.

Effects of this are seen in Harris County where HPD, the sheriff’s and constable’s offices, and smaller entities all follow different oversight policies, the Kinder report stated. HPD’s policies, for example, are written into its labor contract, Lawrence said.

“You adopt a system where there is some level of review and some level of independent oversight,” he said about labor contracts.

The constables themselves have made efforts to standardize some policies. In a joint statement July 27 they said they plan to implement a unified use-of-force policy across all precincts.

However, Fulton added that because the sheriff’s office receives most of its funding from one source, the Commissioner’s Court, the office has a more uniform sense of accountability than the constable’s offices, which receive funding from dozens of neighborhood groups as well as the commissioners.

“The sheriff is much more dependent on the commissioners for money,” he said.

The political landscape

Some of the constables’ most ardent supporters are homeowners associations and civic clubs. Many have been hiring constable’s deputies to patrol their neighborhoods since the county approved the program in the 1980s, the Kinder Institute report stated.

Some of the constables’ most ardent supporters are homeowners associations and civic clubs. Many have been hiring constable’s deputies to patrol their neighborhoods since the county approved the program in the 1980s, the Kinder Institute report stated.Mark Fairchild, the president of the Rice Military Civic Club, said he switched from hiring private security to constables in 2019 as concerns over car break-ins, drunken driving and assaults grew along the neighborhood’s busy Washington Avenue bar district.

“We just felt that we wanted some additional enforcement in the neighborhood that a private security officer cannot provide, particularly the ability to detain and arrest,” he said.

Most of the agreements dictate a neighborhood group will pay for 80% of a deputy’s salary while the county takes up the remaining cost. The deputies are required to spend about 80% of their time in the neighborhood they are hired to patrol and 20% of their time in the county at large. As of 2017, funding for these contracts made up one third of the constable’s office’s budgets, according to the Kinder Institute.

Fulton said wealthier neighborhoods having easier access to the program creates an ethical dilemma as well.

“That’s inherently inequitable,” he said.

Proponents of the contract program—which is also available through the sheriff’s office, though less widely used—said it helps other agencies focus on high-crime areas.

“The constables really do a good job, particularly at theft calls or burglary calls or motor vehicle calls,” Knox said. “When the neighborhood calls them, they’re not calling HPD, which frees up the local police to do other things.”

In early March 2020, Precinct 2 Harris County Commissioner Adrian Garcia proposed the Commissioners Court fund an equity study of the contract program. He pulled it after dozens of supporters spoke out.

“I think the program is serving its purpose, but I am certain that there are ways that it can work better,” Garcia said while asking to table the item.

Whether the allegations within Rosen’s office will prompt a renewed political push to look into the program remains to be seen.

“It raises the question of who do the constables really work for,” Fulton said. “Do you work for the people of your districts, or do you work for the Commissioners Court, or do you work for the people who are contracting you? The answer is you work for all of them.”