It was late July, several days after the U.S. Department of Justice announced it was opening an investigation into the city of Houston over its illegal dumping practices, namely alleged discrepancies in how quickly the city responds to dumping complaints in white neighborhoods compared to neighborhoods such as Trinity Gardens that are largely home to people of color.

Prior to the investigation, representatives with Lone Star Legal Aid—a Houston nonprofit that provides pro-bono legal services to low-income individuals—have alleged illegal-dumping complaints in Trinity Gardens were often ignored or given low priority by the city of Houston, resulting in piles of trash left in vacant lots or on the side of the road for multiple months at a time, claims officials with the city of Houston have strongly denied.

Although there was a clear improvement after the investigation was announced, dump sites soon returned to the Trinity Gardens community, said Amy Dinn, managing attorney with Lone Star’s environmental justice team.

“We went out at the end of September, and all the dump sites were back,” she said.

The alleged quick regression epitomized the challenges the city faces in trying to combat illegal dumping, a priority focus during budget discussions that took place earlier this year for Houston’s Solid Waste Department. Meanwhile, residents in communities illegal dumpers target have been dealing with the fallout, including rodents, eyesores and drainage problems.Since the DOJ announced the investigation, Houston has made additional investments into its Solid Waste Department, one of several city entities that can identify and remove illegal dump sites. However, city officials said properly addressing the problem will likely require more funding.

During a May 18 budget workshop, Mark Wilfalk, executive director of the Solid Waste Department, said funding for the department has not kept up with the exponential growth the city has seen over the past 10 years, with fleet size increasing by less than 1% over that time. A number of efforts are underway to address those challenges, including driver recruitment efforts and explorations into charging a residential service fee.

The latter would help diversify the department’s revenue streams, which would help make residential service more reliable as well as create opportunities for programs that focus on heavy waste, Wilfalk said at the workshop.

Assessing the problem

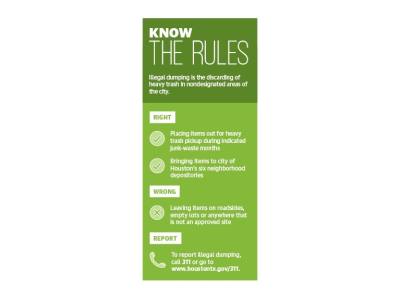

Illegal dumping is the act of leaving trash in an area that has not been designated by the city for pickup. It most commonly occurs in vacant lots and public rights of way along city streets, Dinn said.

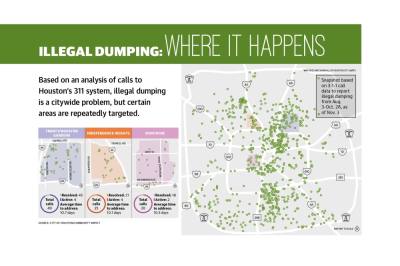

According to public information from the city of Houston, more than 1,350 calls were made to the city’s 311 system between Aug. 3-Oct. 28 that were filed under “trash dumping or illegal dumpsite.”

Data shows the issue being most concentrated in northeast and southeast Houston, but multiple calls were also made regarding Independence Heights, Montrose and Northside communities.

Advocates in Independence Heights said illegal dumping has been a problem in the community for years, long predating the administration of Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner.

District H Council Member Karla Cisneros, who represents the area, funded the installation of security cameras several years ago, and advocates have also met with Houston’s Department of Neighborhoods to work on the issue, but the problem has persisted, said Tanya Debose, executive director of the Independence Heights Redevelopment Council.

“We’re a very proactive community and we try to do our own cleanups, but it saddens us when, the next week, we have another dumping incident,” Debose said.

Mardie Paige, president of the Independence Heights Super Neighborhood, said she wanted to see the city take a more staggered approach to patrolling known dump sites, coming at different times of the day and night so violators know they could be caught at any time.

In the long-range plan for the Solid Waste Department released in 2021, officials attributed illegal dumping to several causes, including residents not knowing how to properly dispose of waste and challenges with enforcement. The city has several approaches to illegal dumping, Wilfalk said.

“Solid waste department staff members can identify and remove illegal dumping while performing their route assignments,” he said in an email statement to Community Impact.

Houston’s target to close an illegal dump site is 30 days after it is reported, according to information from the solid waste department. However, the city’s analysis in 2021 showed it took on average 84 days. More recent data from August through October showed faster response times of around 10 days in Trinity Gardens, Independence Heights and Montrose.

Federal investigation

The Department of Justice’s investigation, which is ongoing, involves examining the city’s response to illegal dumping to detect possible discrepancies that would indicate discrimination against Black and Latino residents.

Illegal dumping is a public health issue, said Kristen Clarke, assistant attorney general of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, in a news release.

“Illegal dumpsites not only attract rodents, mosquitoes and other vermin that pose health risks, but they can also contaminate surface water and impact proper drainage, making areas more susceptible to flooding,” she said.

The investigation was prompted by a complaint from Lone Star Legal Aid related to the city’s practices in Trinity/Houston Gardens, Dinn said. The complaint—which more broadly deals with claims of neglect in Trinity Gardens—alleges illegal dumping of household furniture, mattresses, tires, medical wastes, trash, dead bodies and vandalized ATM machines, among other items in the neighborhood.

“It’s not like these addresses weren’t reported,” Dinn said. “It’s that literally the city did not send out trucks to pick up the trash and did not do anything to try to catch the people that were taking the stuff to the neighborhood to dump in. There’s just a complete absence of enforcement.”

In response to the DOJ announcement, Turner said in a news release the investigation was “absurd, baseless and without merit.”

“The city follows up on 311 complaints about illegal dumping and aggressively pursues those responsible for illegally discarding debris on public or private property without the owner’s consent,” Turner said.

City action

At its Aug. 16 meeting, Houston City Council approved $2.9 million for the “emergency purchase” of bulk waste collection services for the months of August and October. The move followed up on warnings issued by the solid waste department in May that staffing shortages combined with an anticipated 43% increase in bulk waste volume during summer months would result in “severe delays” and “compromise the health, safety and community aesthetics citywide.”

Several months later, at its Oct. 4 meeting, the council approved just over $319,000 to purchase 10 security trailer camera systems. The cameras are being used in the northeast and southeast areas of the city to provide 24/7 surveillance in rights of way and vacant lots where illegal dumping has been a consistent problem. At the May budget workshop, Wilfalk said having a code enforcement team within the Solid Waste Department could also help.

Dinn said she was glad to see more investments were being made and that she is hopeful the investigation will bring solutions.

“Finances are always a problem, but it’s more than that,” she said. “It takes a mindset for them to actually enforce enough that people are deterred from continuing to dump in areas. That’s what I’m hopeful for.”