Between 2010 and 2020, roughly 95% of population growth in Texas was driven by people of color with most of the growth occurring among Asian, Hispanic and Black communities, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau. That population growth also brought two new congressional districts to the state for a total of 38 districts.

However, when looking at citizen voting-age populations, the number of congressional districts with white majorities across the state increased by one under the new maps from 22 to 23. At the same time, the number of districts with Hispanic majorities and Black majorities both fell by one—from eight to seven and from one to zero, respectively—and the number of districts with no racial majority grew by three, from five to eight, according to the Texas Legislative Council.

Although those trends do not explicitly prove discrimination, Michael Li, a redistricting expert with the nonprofit law and policy institute Brennan Center for Justice, said the trends do raise questions about potential violations of the Voting Rights Act.

“The real question is: Are there more opportunities for the minority communities that provided most of the state’s growth?” Li said. “There doesn’t seem to be, and that raises a lot of red flags about potential discrimination.”

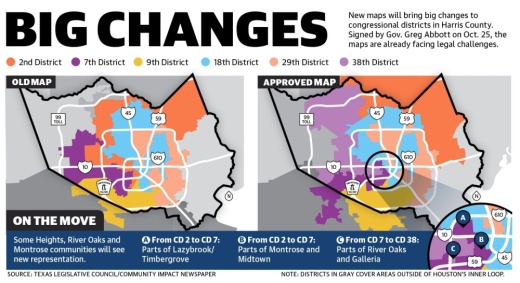

Changes in Harris County center on the redrawing of U.S. Rep. Lizzie Fletcher’s 7th District, which absorbs some communities formerly covered by U.S. Rep. Dan Crenshaw’s 2nd District, including parts of Lazybrook/Timbergrove, Midtown, Montrose north of Hwy. 59 and University Place and Braeswood Place south of Hwy. 59. West University Place itself will remain in District 7, as will the city of Bellaire.

Meanwhile, parts of the Willowbend and Westbury areas were moved out of the 7th District to U.S. Rep. Al Green’s 9th District. The River Oaks and Galleria areas move out of the 7th District to the new 38th District. Although the maps were signed by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott on Oct. 25, lawsuits have been filed challenging their legitimacy.

In an Oct. 19 statement, Fletcher said she had concerns about the mapmaking process but was prepared to represent her new constituents.

“While I have concerns about the redistricting process, the maps, and the failure to reflect the population growth of Latino, Black and Asian American Texans over the last decade, ... I remain committed to serving the people of Texas’ diverse and dynamic Seventh Congressional District now and in the future,” Fletcher said in a statement.

State Sen. Joan Huffman, who served as the chair of the Senate Redistricting Committee, defended the maps at several public hearings that were held throughout the process and said they comply with the Voting Rights Act.

“We drew these maps race blind,” Huffman said at a September public hearing on the maps. “We have not looked at any racial data as we drew these maps.”

History in the courts

Redistricting was tackled as part of a third special session of the Texas Legislature called by Abbott. The session began Sept. 20 and ran through Oct. 19, when the new maps were finalized.

According to the state’s redistricting website, the two basic requirements for the process are that districts must have as close to equal population as possible, and districts cannot limit voting based on race, color or language group. Under the U.S. Constitution, lines must be redrawn every decennial census.

A 1973 U.S. Supreme Court case, White v. Regester, defined “equal population” as a plan in which the most populous district has at most 10% more than the ideal district population—or the state population divided by the number of districts.

Richard Murray, a political science professor at the University of Houston and former redistricting adviser to the Texas Legislative Black Caucus, said the process allows for redistricting committees to “crack” or “pack” populations, giving parties more control.

“We’re the only state that gained two seats in the country,” Murray said. “There’s immense pressure [on Republican lawmakers] to do something.”

One change to the process this year was the removal of preclearance, which the U.S. Supreme Court struck down in 2013. Preclearance was a provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which required states with a history of racial discrimination to submit redistricting plans to the federal government before they could be approved.

Without preclearance, Li said the lawmakers drawing the maps had little incentive to take concerns over potential discrimination into account.

“Now, there’s nothing that prevents Texas from being as aggressive and discriminatory as it wants and basically daring people to go to court to get the maps struck down,” he said. “It is a critical piece of protection that is gone now.”

A local look

Roughly 200,000 people were removed from the 7th Congressional District from parts of western Harris County, while another 200,000 were added from areas around Sugar Land and Richmond.

The changes will ultimately make Fletcher’s seat more racially diverse and more populated with Democratic voters, Li said.

The newly created 38th District will cover a lot of the area formerly under the 7th District. Li said the district is solidly Republican.

Wesley Hunt is a Republican who announced he will run for the 38th District, which he said covers the Spring and Klein area where he lives and grew up. Since announcing his intentions to run, Hunt said he has received an "incredible amount of support."

On the campaign trail, he said concerns he has heard from voters in the new district have included immigration, the rising cost of goods and the suffering of the oil and gas industry.

“Running for this seat means everything to me because it’s home for the Hunt family,” Hunt said.

New Texas House maps resulted in the 148th District, which formerly covered the Heights, being redrawn so that it no longer covers any of Houston’s Inner Loop. State Rep. Penny Morales Shaw, a Democrat who holds the seat, said 30% of her old district was carried over into her redrawn district. Several historically Hispanic communities, including Northside and Lindale Park, were removed from her district and put into others, she said.

“Fifty percent of the population growth is attributed to Hispanic populations, and instead of representing that in the way the maps were drawn ... they changed District 148 into what they call a coalition district,” she said.

Representation for the Heights, River Oaks and Montrose is largely unchanged under new Texas Senate maps. The Texas Senate district covering Bellaire, West University Place and most of the Meyerland area is also changing under the new maps from Huffman’s 17th District to Democratic Sen. John Whitmire’s 15th District.

Preserving power

Both Murray and Li said increased diversity in the suburbs likely played into how boundaries were drawn.

“The minority populations have grown dramatically, but it has also dispersed,” Murray said. “There’s a lot of Black and brown flight to the suburbs, more than previous decades.”

Maps broadly seemed to be drawn with the goal of bolstering incumbent advantages, Li said. Meanwhile, several lawsuits have already been filed challenging the new maps, including a lawsuit by the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund arguing the maps are intentionally discriminatory. The new maps will first be used during 2022 midterm primary elections.

An early version of the proposed maps drew U.S. Rep Al Green and U.S. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee into the same district, prompting another wave of criticism that the maps were trying to pit two Black members of Congress against each other.

Several communities that have been in Jackson Lee’s 18th District for decades were slated to be removed and placed in Green’s 9th District, including the historic Black communities of the Third Ward and Sunnyside. However, lawmakers ultimately put those communities back in Jackson Lee’s district following the wave of criticism, along with Jackson Lee’s district office.

“I am pleased that the House adopted an amendment drawing Sheila Jackson Lee back into Congressional District 18, returning the district closer to its present configuration and doing so in a way I believe is compliant with the law,” Huffman said at an Oct. 19 hearing where the maps were adopted.

Jishnu Nair contributed to this report.