“I think the very-big-picture view of this is that the Corps has chosen what seems to be the simplest options from an engineering perspective,” said Wendy Duncan, co-founder of the Barker Flood Prevention Advocacy Group. “However, they are the absolute most difficult from a political perspective.”

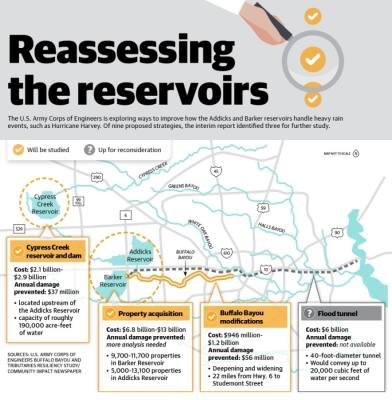

The Oct. 2 interim report considered nine approaches, but its cost-benefit analysis favored continued study of three: constructing a Cypress Creek reservoir, deepening and widening Buffalo Bayou, and acquiring more properties around the Barker and Addicks reservoirs—as well as a fourth alternative that includes a combination of efforts.

“We would like to see more data on how they came to these conclusions,” said Auggie Campbell with Houston Stronger, an advocacy group that formed after Hurricane Harvey. “Excavating Addicks and Barker is something that could happen very soon, and every shovelful of dirt is a shovelful of water out of someone’s house.”

In a Nov. 15 town hall hosted by U.S. Rep. Lizzie Fletcher, Corps officials acknowledged that because of public feedback, they would give further study to a proposed underground flood drainage tunnel, a project that the Harris County Flood Control District is also evaluating.

Interim ideas

One of the plans identified for further study proposes 22 miles of channel modifications to Buffalo Bayou, deepening and widening its banks and lining the bottom with concrete. The Corps found that this approach might be almost as effective at reducing flood damages as a tunnel at a lower financial investment, but local advocates argued the environmental costs are not yet accounted for.

“Buffalo Bayou is teeming with life, but this would kill everything in it,” said Susan Chadwick, executive director of Save Buffalo Bayou. “Nowadays, they have to mitigate for that—the environmental impacts. I can’t imagine how they’d do it.”

The Buffalo Bayou Partnership also voiced concerns in an Oct. 27 letter to the Corps in which they argued the modifications would be “damaging” to Buffalo Bayou Park and that the proposed 3,093 acres of estimated mitigation would be “unattainable.”

Duncan, of the Barker flood group, and Campbell, of Houston Stronger, added that modifying the bayou and building a third reservoir would also involve a difficult acquisition process and some of the most expensive real estate in the region.

“Those two ideas would be very unpopular and would require a lot of environmental investigation and mitigation and, in all probability, a lot of litigation,” Campbell said.

However, Col. Timothy Vail, commander of the Corps’ Galveston District, emphasized that the overall study is a work in progress and that public support will be a factor.

“The way ahead has to be a joint solution between the public and the Army,” Vail said at the Nov. 15 town hall.

He added that any project plan must also include the backing and financial commitment of its local sponsor, the flood control district.

Further review

David Abraham, a community resiliency researcher at Rice University, said the response to the report should help the Corps craft a more sustainable, responsive plan.

Army Corps officials said its next report, which will look at feasibility and environmental impacts, could be ready for public review in early 2021.

“The project sponsor does their best to hire their experts—which are going to be engineers, for the most part—to develop the alternatives. But then, equally should be the opportunity to evaluate the public’s contributions,” he said. “If the general public is able to articulate and technically show the opportunities that could be involved, ... then that has to be considered.”

The Corps has not been charged with developing a comprehensive flood strategy, he said; instead, it is focused on the reservoir dams and how they will handle future overflows.

“If I were to simplify it, they are saying that the dams themselves are fine, but they need to be able to move water more quickly through the bayou,” he said.

Even that conclusion was questioned by Chadwick, who suggested that a fast-draining bayou could back up during storm surges.

“All that water won’t go where they want it to go,” she said. “We will need more creative ways of holding that water and slowly releasing it.”

However, Abraham said, whether to channelize Buffalo Bayou or to adopt a nature-based approach is not an all-or-nothing proposition.

“It can be both and be a more sustainable approach,” he said. “But you do have to go in and manage it because it can’t function naturally in an urban environment.”

To get to a sustainable answer, advocates said, the public and the Corps will have to find a middle ground.

“It would be a big win for the Corps to develop a plan that gets more creative and collaborative with local landowners and entities who will ultimately be partners in this project,” Campbell said.

Shawn Arrajj contributed to this report.