“Our neighbors, they’re supporting us, you know, as much as they can,” Diaz said. “We’re here and just praying, hoping and hoping this will pick up.”

Orders to limit social activity and avoid unnecessary outings have brought the vibrant restaurant community in the Heights, River Oaks and Montrose to its knees, and owners worry without significant local and federal support, many could be forced to close. The Texas Restaurant Association has warned that long-term closures could result in 1 million jobs lost across the industry.

“The closing of the dining rooms and all the implications of that has been devastating. We’re a social industry,” said Melissa Stewart, executive director of the Greater Houston Restaurant Association. “Take-out is fine and works for some, but not everyone. And restaurants have a lean profit margin. That’s been the model forever and ever—that’s no one’s fault.”

An increasing number of restaurants have announced they were closing temporarily, with an unclear outlook as to when they could be fully reopened.

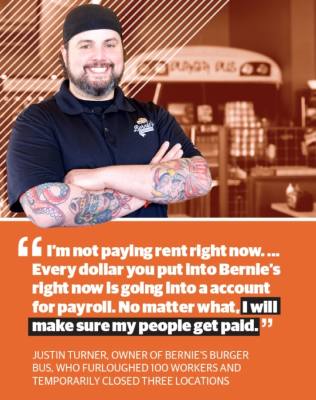

“Even if today they said, ‘OK everything’s back to normal,’ I don’t think I’d be able to hire back all the same employees,” said Justin Turner, owner of Bernie’s Burger Bus, which had to temporarily close three of its four locations and furlough 100 employees. “I’d also have to still figure out how to get cash for groceries and supplies. It would take some time.”

Until that day comes, restaurants are adapting, community efforts are growing, and a patchwork of funding could soon begin to serve as a lifeline for Houston’s food and beverage industry.

Getting creative

Many restaurants got ahead of the outbreak by stepping up sanitization efforts, expanding the use of gloves, wiping down surfaces and doorknobs, and other measures.

“A lot of it is the type of stuff that we usually do anyway, but we’re being even more careful,” said Jason Mok, a partner at FM Kitchen & Bar near Washington Avenue.

With the decision by city and county officials to end dining services, takeout became the order of the day. At Relish, a restaurant in the River Oaks area, owner Dustin Teague said a surge of to-go orders was met with a rethinking of menus and personnel.

“One thing that we’ve done is we’ve gone to an operator mode, one person designated to pick up the phone. ... We realized right away that that was the most important thing,” he said.

Even with the best adjustments, he said business is down as much as 80%.

Demand for delivery prompted more restaurant owners to sign on to services, such as Uber Eats, Favor and Grubhub, even among those who, like Diaz at Guadalupana, had avoided them because of the cut they take out of each transaction.

“But now it’s about thinking about volume,” Diaz said. “OK, they’re gonna reach so many customers. You know, they take 30% of it. ... Is it worth it right now? I believe so.”

With grocery stores struggling to keep up with an anxious public, restaurateurs also saw an opportunity to put unused supplies—including toilet paper—up for sale.

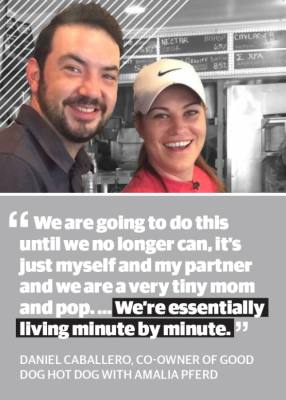

Inspired by New York-style bodegas, Amalia Pferd and Daniel Caballero, owners of Good Dog Hot Dog, put out tomatoes, onions, avocados, paper products, flour and sugar up for sale.

“We’re continually restocking, and we’re selling everything for so cheap,” Caballero said.

Because restaurants have access to different distributors and local farms, they have been able to tap into products that might fly off store shelves. To help encourage more restaurants to follow suit, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott formally endorsed this practice March 24, provided certain health protocols are followed.

Despite these efforts, almost all on-site dining establishments are losing business, compounded by the fact that many patrons are staying home out of caution and have stocked up on groceries.

“If you think about it, if you’re working at home but your life otherwise isn’t affected, your days aren’t that different; you still work a normal day, just at home,” said Stewart, of the restaurant association. “So you may reasonably be able to spend what you’d normally spend dining out, getting lunch and maybe a coffee. These businesses are depending on that.”

Community connections

Owners also said some of the easiest ways to help a favorite local restaurant are to buy a gift card and tip generously.

“A $500 gift card is almost like loaning us $500,” Teague said. “And keeping gratuity in mind, it doesn’t go to me, it does to the hard workers who have taken a drastic pay cut.”

Despite the struggles, community-minded owners are also finding ways to contribute and assist their peers and first responders.

When Austin-based restaurant Be More Pacific, which recently opened in the Heights, began serving meals to local hospitals, Abe Chu, CEO of the startup fundraising platform Nextseed, saw a way help both industries.

“We had been talking about raising some kind of disaster relief fund,” he said. “But as an investment platform, we are not easily set up to do that. So we looked around, ‘Are there one-off instances of someone doing something creative and scrappy that we could formalize and scale?’”

By partnering with Impact Hub Houston, Chu said Nextseed was able to quickly create the Local Impact Food & Entrepreneurship fund, with the goal to raise $10,000 to supply meals to hospital staff and first responders by partnering with local restaurants. Nextseed, which has helped fund the launch of several Inner Loop restaurants, was able to draw on its own network and help connect them with potential orders from hospitals.

“We are starting incrementally so we don’t screw it up. We have 10 businesses to start with, and we’re mapping out the first week. As soon as funds come through, we’ll start placing orders,” Chu said. Restaurants include Be More Pacific, Peli Peli, Breakfast Klub, Texadelphia, Potin and Toasted Coconut.

Once the model is proven and more donations roll in, he said the fund can scale up and even expand to other cities.

Other efforts are more small scale, such as a recent offering by Mico’s Hot Chicken. Co-owner Kimico Frydenlund, a former nurse, said it only made sense to offer specials for other nurses—giving away as many as 50 meals.

Because her business began as a food truck, it has not yet felt the effects of the dining room ban, but she had hoped to open her brick-and-mortar shop in the Heights soon.

“We’re ready, permitted and waiting to fully open,” Frydenlund said. “We’re blessed to see not a real loss yet. But that could change; we’ll see.”

Recovery mode

With a federal stimulus bill signed into law and others inching toward passage as of press time, business owners are eager to hear about any programs that could help them survive.

“The reality is there’s not going to be one path to a solution,” Stewart said. “It’s going to be a loan; it’s going to be incentives, some rent abatement here and there, and federal help.”

Local and state-level efforts could make a difference as well, and some restaurant leaders such as Bobby Heugel, owner of Anvil Bar & Refuge, Better Luck Tomorrow and others, have begun organizing grassroots efforts to demand temporary relief from paying beverage taxes, which were due March 20, just days after restaurants were ordered to suspend service, as well as asking for rent relief to help restaurants and landlords alike.

Thus far, the state’s main response has been to loosen some restrictions, such as allowing to-go alcohol sales. Meanwhile, the state lobbying arm of the industry, the Texas Restaurant Association, is launching a relief fund that is open to any restaurant owner to apply for immediate aid.

The Small Business Development Center, an extension of the federal Small Business Administration, is recommending that all small businesses, including restaurants, apply for federal economic injury loans regardless of whether they are committed to borrowing through the low-interest program. Under the new federal law, a portion of the debt can be forgiven.

“Any relief for small business is going to come through SBA,” said Steven Lawrence, executive director of the SBDC’s Houston district office. “And in order to get any kind of relief, whether it is a loan or whatever undisclosed relief, such as grants, down the road, you have to be in that queue.”

The SBA’s economic injury loan program is fielding applications, he said, and funding is being disbursed. The SBDC is helping guide business owners in what they need to complete applications, but Lawrence said many are giving up when they learn the help is not immediate. An applicant can expect to receive a response within a week and funds deposited within four weeks, he said.

“The problem is most small businesses need cash right now, and we’re struggling to get that quick cash to them,” Lawrence said.