“If I leave, I have to find a way back because it’s the only place I’ve felt at home my whole life,” said Ganz, who now lives with their wife near the University of St. Thomas.

For Ganz, a native of rural Southwest Louisiana who identifies as nonbinary, Montrose has been and continues to be the most accepting place they have lived. And for a while, Ganz said it was affordable with wages in construction, retail and restaurants, but that is no longer the case.

“Kids today coming from rural Texas, who are still fighting hate on a daily basis, can’t afford to come here and feel like they are part of a neighborhood and a community,” Ganz said.

A shift in thinking about affordable housing as a citywide effort has been difficult to execute in Montrose where land prices keep increasing.

The city’s strategy has recently moved away from approving housing on large tracts of inexpensive land and toward encouraging distribution of housing throughout the city. The need for more affordable housing however, is strong in most areas of town, Council Member Tiffany Thomas said.

“What we were getting was concentrations of poverty,” said Thomas, who is the chair of city council’s Housing and Community Development Committee. “But the property value in all of our neighborhoods within the city is increasing.”

A possible lifeline could come from the Montrose Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone, which collects a portion of taxes levied in the area to use specifically in the area. It has projected it can spend close to $40 million toward affordable housing initiatives in its 30-year plan, but the TIRZ is still in the study phase to determine which actions it can take.

“There is a commitment by the board to increase the diversity of housing type and incomes within the zone,” TIRZ board member Lisa Hunt said in a written response to questions.

Worsening trend

Although Montrose still maintains a significant population of renters, luxury high-rises and newly renovated apartment buildings are increasingly dominating the market.

Nearly 82% of all apartment units in the area are classified as Class A, or luxury level, according to ApartmentData.com’s census of the area, which collects data from larger complexes with on-site offices. Since March 2015, the area has added nearly 5,500 of these higher-priced units and lost almost 300 lower-level units. The area’s apartment stock increased 50% over that period to nearly 15,700 units.

The neighborhood has a variety of other rental types such as duplexes, triplexes and smaller apartment buildings. A preliminary study by the TIRZ, run by the analytics firm January Advisors, observed a monthly one-bedroom rental rate of $1,295 and even lower rents among older properties.

“The housing stock in Montrose is older and many of the multifamily units are aging. Until recently, there have been few incentives for owners to invest in renovation of multi-family dwelling units,” Hunt wrote in the TIRZ’s response to questions. “Redevelopment is driving up costs but not the only factor.”

According to the housing study, nearly 70% of residential land in Montrose is single-family homes, townhomes or condos, which tend to be more expensive. By contrast, duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes and small apartment buildings, which typically have lower rents, make up less than 10% of the area’s residential land use.

A combination of stagnant wages and increasing property values driven by the area’s growing popularity is preventing many from having many housing options, if any.

“It was beneficial to bartend in places like Montrose that did have a bar scene, but the cost of living went up, and our pay never did,” said Slim Bloodworth, a bartender and comedian who used to live in Montrose but moved to the Fifth Ward in 2016, seeking a lower cost of living.

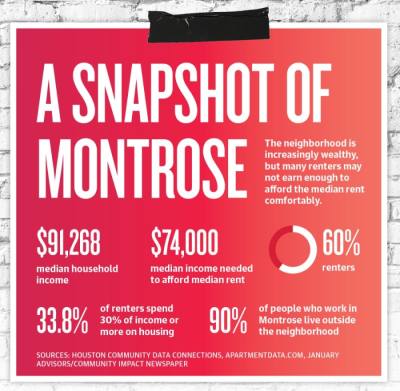

January Advisors’ report noted a household needs to earn $74,000 a year to cover the $1,850 median rent in Montrose, assuming housing costs are kept at 30% of a household budget.

Now studying to earn a degree in political science from the University of St. Thomas, Ganz said they were so concerned with the trend that they launched a campaign for City Council in 2019 centered on housing. Although Ganz did not win the election, they said the process connected them with fellow tenants battling displacement.

Now, those who work in the same industries as Ganz commute to the neighborhood and live elsewhere.

About 90% of the people who work in Montrose live outside of the neighborhood, according to the TIRZ’s preliminary needs assessment, a draft of which became available in December.

Seeking solutions

Industry experts said affordable housing cannot be achieved as a commercial venture alone.

“It has to be a public-private partnership. If you own a home, look at your own housing costs. I imagine taxes alone can be 25%-30% of the monthly payment,” ApartmentData.com President Bruce McClenny said. “Apartment operators and developers are under that even more so because they can’t get things like a homestead exemption to limit the increases. So their taxes can increase 20% or more. There has to be a public role in working with that.”

On Feb. 2, a venture by Cleveland based-developer The NRP Group and backed by the Houston Housing Authority broke ground on a new mixed-income apartment community at 2400 W. Dallas St. Half of its more than 360 units will be allocated to tenants earning below 80% of the area’s median income.

“This is part of our citywide effort to solve Houston’s affordable housing crisis, and we are proud to partner with NRP to increase affordability in Montrose,” HHA Board Chairman LaRence Snowden said in a news release.

Losing itself

More than any other issue, current and former residents said a lack of affordable housing poses a threat to Montrose’s identity.

“There were tattoo artists and artists of all sorts. We used to see belly dancers and tai chi and people who ran yoga studios out of their own homes. Band members and artists lived there because it wasn’t expensive, and there was a peaceful, community mindset,” said Bloodworth, who was once named the “unofficial mayor of Montrose.”

To some extent, Eepi Chaad Director of Montrose-based Art League Houston said she believes Montrose will always remain the center of the arts community.

“There’s institutions like the Menil [Collection] that are always going to keep Montrose part of the heart of the arts in Houston,” she said. “It’s great to see the Inner Loop really be revitalized, but we need to spend a lot more effort on making sure that affordable housing is something that we take responsibility for as a city.”

Over time, Ganz has been repeatedly priced out of apartments with rising rents, moving to the Heights, Westchase, Sharpstown and Pasadena temporarily. Ganz’s story is not unique in Montrose, where bohemian and counter-culture roots led to a widely appreciated arts and dining scene that has drawn new residents and bolstered property values.

Chris Barry, the owner of the gay bar Buddy’s, said he was drawn to Montrose from Beaumont in the late ‘90s for the same reason as Ganz.

“I’d never seen so many people who were gay—and not just in one bar, but in a whole area of town,” he said. “It was a sense of not just being yourself but not having to worry about it.”

The artistic spirit that fostered the area’s inclusivity, however, is now drawing in developments that push creatives and LGBTQ residents out.

“They are being priced out because the LGBT community in large part lives in poverty because of disenfranchisement and systemic discrimination,” said Tammi Wallace, the founder of the Greater Houston LGBT Chamber of Commerce.

Moving forward, Bloodworth said she hopes new developments can acknowledge the area’s history, especially with memories of the height of the AIDS epidemic still fresh in many residents’ minds.

“As per the request of the deceased from the AIDS epidemic, we would go scatter ashes at [Mary’s Naturally Bar], and then it got turned into a parking lot, and I can’t tell you how upset most of us were when that happened,” she said.

Ganz said change in the neighborhood is inevitable but not always unwelcome.

“The fact remains that new businesses can open,” Ganz said. “But are we going to foster an environment where diverse and unique people and local businesses can come and make it?”