Harris County Commissioners Court created the Justice Administration Department in 2019 to identify solutions and facilitate meaningful changes to the system.

“We’re looking at addressing the necessary systemic changes that need to happen [based on] data [and] best practices so that violence can be stopped, the trauma from that violence can be addressed, [and] the reduction of racial and economic disparities can also be addressed all while attempting to minimize criminal justice exposure as much as possible,” JAD interim Director Ana Yáñez Correa said.

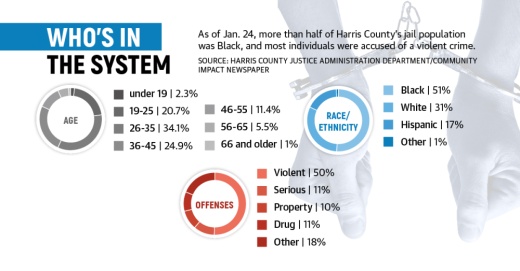

Since its inception, the JAD has created public dashboards presenting data on the jail population, county traffic stop demographics, caseload data for private indigent defense attorneys, and crime trends comparing Harris County to other major counties across the state and country.

This data and collaboration with other criminal justice agencies help JAD officials develop recommendations for potential improvements.

“Our clients falling through the cracks happens so much because we’re working with this system that is constantly inundated and stretched. People get lost in the system, and if we’re able to look at those trends and identify where those gaps are and address them, I think we would be much better off,” said Stephanie Truong, program director of Beacon Law, a program of Houston-based nonprofit The Beacon, which serves local individuals facing homelessness.

Drew Wiley, CEO and founder of Restoring Justice, another Houston-area nonprofit, said when he started the organization in 2016, 97% of indigent cases were appointed to private attorneys who were juggling up to 10 times the state-researched maximum caseload. Six years later, that number has decreased as the county public defender’s office takes on more indigent cases. But Wiley said there is still much work to be done.

“The hardest thing is that the people in the jail are not feeling the effects of anything that’s been done by system actors,” he said. “It’s always Commissioners Court, in response to George Floyd protests—they want to issue these studies and these narratives. And that’s fine, [but] show me one person in jail that has been positively impacted by the action you want to do.”

Challenges in the system

JAD Special Projects Administrator Stephanie Armand said a series of disasters in recent years—from Hurricane Harvey to the pandemic—has put the county at a disadvantage.

Inefficiencies, such as judges sharing courtroom spaces and courts shifting to Zoom operations for several months, meant case backlogs grew significantly, Armand said. Recommendations from the JAD to help chip away at that backlog included providing additional spaces for jury trials and bringing in resources to assist with logging evidence at the sheriff’s office.

Armand said the case backlog declined from 95,000 in June to 89,000 in November, crediting the Commissioners Court’s investments in jury operations as the most significant factor.

“In a different world, [the JAD] would be an agency that can proactively look at reports and do a lot of things that address issues that people are curious about, but in this world right now, it’s been about damage control, about supporting Commissioners Court, helping as many players as possible to get through some of these challenges,” Correa said.

Still, data from the JAD has highlighted challenges, including racial profiling in law enforcement agencies across the county. A June report found Hispanic drivers were more likely to receive citations and Black drivers were more likely to experience bodily injury because of the use of force than other racial and ethnic groups.

“I think it’s been proven over and over again through research and data that there is a racial injustice problem in Harris County,” Wiley said. “I think things like that is what JAD is pulling together to hopefully convince more people ... to start acting to change things for individuals.”

Addressing public safety

In addition to investing in jury operations, Commissioners Court has taken steps to help reduce crime and alleviate system challenges.

In 2021, the court approved a $50 million neighborhood cleanup initiative in high-crime areas and launched both the Holistic Alternative Responder Team and the Gun Violence Interruption Program. Funding for law enforcement agencies has also increased 22% in the past five years, according to county budget data.

Howard Henderson, professor and director of the Center for Justice Research at Texas Southern University, said the JAD’s work is helping the county rethink its approach to justice.

“I think the social work model that Harris County is implementing is the right thing to do because many times mental health cases and domestic violence cases turn sour unnecessarily only because we don’t have the trained personnel dealing with them,” he said.

Harris County Precinct 3 Commissioner Tom Ramsey announced in January the launch of a new crime task force to reduce violent crime. According to JAD data, the county’s crime rate overall has decreased by about 6% since 2015. However, crime was up year over year in both 2019 and 2020, and Harris County’s crime rate was higher than that of Los Angeles, Kings and Cook counties during that time.

Harris County Precinct 4 Constable Mark Herman said he believes too many criminal cases are being “arbitrarily dismissed.” In late 2021 he began refiling cases that had been dismissed by judges, he said.

“This is a very bad message not only to our citizens out there, but it sends a message to the criminals, and it emboldened them to make them to go out and commit more crimes and make them victimize more people,” Herman said.

Truong said Beacon Law received a $50,000 JAD grant last year to look at legal services from an equity standpoint. The grant allowed Beacon Law to reach more clients by expanding the income eligibility for services.

The organization works with clients who are chronically homeless, but it also serves clients living paycheck to paycheck who may be on the verge of homelessness.

“It’s a daily struggle for some people who have tried to scrape by and have done their best with the resources that they have, but there definitely is a lack of support and resources for people out there in order to break the cycle and move forward with their life,” Truong said.

Implications on individuals

The JAD plans to continue conducting research and developing dashboards this year. A use-of-force policy report and a bail bond dashboard are expected to be released in the first quarter, Correa said.

“There’s a lot of talk about bond and bail reform, which from a system perspective is the most obvious example of, ‘If you’re poor, you can’t get out.’ Being poor or rich is what’s driving justice over there,” Wiley said.

Other ongoing areas of study deal with addressing inequalities in the system; supporting survivors of crime; and addressing the root causes of crime and criminal justice involvement such as mental health, homelessness, substance use and poverty, Correa said.

Restoring Justice is one of the only indigent defense providers in the country also offering trauma-informed counseling, Wiley said, because he found trauma is often at the root of clients’ circumstances.

“The direct response to those ailments, to those root causes, has been to throw someone in jail, and all that does is destabilizes, and it makes the problem worse,” he said. “You could take a fraction of those dollars spent on the policing system, the jail system, the prison system and do the upfront mental health, homeless, substance addiction treatment ... to prevent all of that wasted money and help that person’s life as well as help society.”

Shawn Arrajj and Jishnu Nair contributed to this report.