“The problem is that the appraisal district has an open domain to raise your appraisal every year, and every year they raise it to the max that they’re allowed by law—no matter what the marketplace says,” she said. “An issue for me is I’m retired and live on Social Security. My house was paid for, but every year they raise the value of my house so much that ... it’s almost like you could be taxed out of your house that you paid for.”

Thomas was one of more than 415,000 Harris County accounts whose valuations were appealed last year—a record number and part of an upward trend of residents pushing back on their property tax bills.

Chief Appraiser Roland Altinger said as the demand for residential properties rises, their values have increased by 8%-10%, and commercial property values have gone up 9% since last year.

While protesting is becoming increasingly popular, results are mixed; the process frustrates some homeowners; and some neighborhoods appear to be more successful than others.

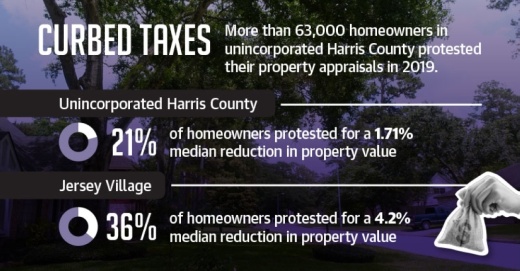

For example, 36% of Jersey Village homeowners protested their appraisals in 2019 for an average of 4.2% savings. In the Willowbrook area, 12% of homeowners protested, and they ended up saving about 1.67% on their values in the same year, according to data from January Advisors.

Protests offer homeowners one tool to reduce their tax burdens. Meanwhile, some state lawmakers are pushing for additional reforms to the property tax system that was overhauled in 2019 with Senate Bill 2.

“[Based on] the public policy we passed in the 2019 legislative session, actually as values go up, tax rates will come down—and especially on school taxes,” said state Sen. Paul Bettencourt, R-Houston.

Setting values

Each spring, the Harris County Appraisal District—an independent entity separate from the county government—begins mailing property owners their market and appraised values for the tax year. The appraised value reflects any exemptions a property owner might have, such as a homestead exemption.

In turn, these appraised values inform taxing entities such as cities and school districts, which set a tax rate to generate revenue. In lieu of a state income tax, property taxes fund a wide range of services, HCAD Chief Communications Officer Jack Barnett said.

“Property taxes are what support critical local services, primarily education but also police, fire, road maintenance, parks, libraries, all of those things that make a community more desirable to live in,” he said.

“Property taxes are what support critical local services, primarily education but also police, fire, road maintenance, parks, libraries, all of those things that make a community more desirable to live in,” he said.Appraisal districts use a process called mass appraisal, which looks at comparable properties in an area to determine a base level of market value. But on a house-by-house level, this can result in inconsistencies.

Drew Wasson, a Jersey Village city council member who has lived in the area since 2004, said the appraisal district’s algorithm can make it difficult to pinpoint these discrepancies in valuations.

“They insert maybe a few market variables, and then all of a sudden you let the computer go to work, and sometimes based on square footage or measurements that they may have or other things, they’re going to spit out a number that just is inconsistent with other portions of the neighborhood,” he said.

Jersey Village residents have seen notable escalations in their property values especially over the past five years as both land and housing prices have increased, Wasson said. Since the county includes land values along with structures, a property value can also increase year over year as the area becomes more attractive.

“This is kind of where it gets tricky between appraisal and real estate because if the properties in your neighborhood go up because it’s a desirable neighborhood, the market value of your house is going to go up,” Barnett said.

Texas nondisclosure laws prevent sales prices from being released, so the county relies on data provided by third-party firms to get a sense of real estate trends. The county also considers alterations—from new fences to a patio addition—as well as the overall quality of a structure.

The appeal of protests

With an appraisal on hand, homeowners face a choice: either accept the number or file a protest—either on their own at no cost or by hiring a consultant. The protest deadline typically falls May 15 or 30 days after the notice of appraised value was mailed, whichever is later. The county accepts both paper forms or online submissions through its iFile system.

“The purpose of the property tax system is to basically value property in market,” Bettencourt said. “So, if you have a case and you think that your property value is not correct, then you should protest.”

The filing is followed by an informal meeting with a district appraiser, who might provide a revised appraisal. The owner can accept or reject it, and if they disagree, the case can move to the Appraisal Review Board.

This board serves as an independent body to resolve disputes between property owners and the appraisal district and holds 1,500 panel hearings daily from May through August. Appellants have 15 minutes to state their case to three board members.

A property tax consultant, who is paid by taking between 20%-50% of the taxes saved, is the preferred choice in Harris County with over 68% of property owners choosing that option when pursuing a protest. However, according to a 2019 January Advisors report, there was not a significant difference in performance between homeowners who hired a firm compared to those who led a protest on their own.

Wasson said he has chosen to file his own protests in the past due to the cost savings and because it gives him more control over the entire process.

“A property owner could very well get better results than a consultant because they are so much more familiar with the property,” said Darlene Okonski, a homeowner tax consultant with Marvin F. Poer and Co.

Further review

Further reviewProtest activity has been on an upward trend for at least the past decade with the number of accounts under appeal increasing almost 30%, according to HCAD data.

These appeals are increasingly settled beyond the ARB process with 10 times as many cases going before arbitration in 2019 as in 2010 and almost three times as many cases going into litigation. Many of these cases involve multimillion-dollar commercial, industrial and multifamily properties, Barnett said, which are subject to higher rates of increases.

Reforms in the 2019 legislative session largely targeted taxing entities, imposing a 3.5% cap on annual revenue increases and offering an infusion of state funds to allow for school property taxes to drop slightly.

Bettencourt supported several follow-up bills that passed this spring. Some of these actions included allowing people to make corrections to appraisal errors and clarifying that disaster exemptions are only for physical disasters and not for events such as pandemics or droughts.

In the meantime, taxpayers continue to have the protest process to try to bring their own tax obligations down each year. Thomas said she believes everyone should protest their appraisal regularly to keep tax bills manageable.

“I would advise everyone to do it—whether you do it yourself or you choose a company that will represent you. It will be to your advantage if you get it lowered,” she said. “They’re going to raise the amount of your appraisal every year, come what may.”