Dr. Manda Hall is the associate commissioner of community health improvement for the Texas Department of State Health Services and is one of 17 members of the Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee. This group studies pregnancy-related deaths to identify trends and contributing factors, and make recommendations.

The committee’s most recent report from September 2020 stated the following causes accounted for 82% of maternal deaths in Texas: cardiovascular and coronary conditions, mental disorders, obstetric hemorrhage, preeclampsia and eclampsia, infection, embolism, cardiomyopathy and pulmonary conditions.

“When we look at maternal mortality, I think we know that it’s kind of multifactorial,” Hall said. “Through our case review and looking at the data, we know what we see as far as those leading causes of maternal death, and we also know that there are specific groups that bear the greatest burden of maternal mortality, meaning ... Black women.”

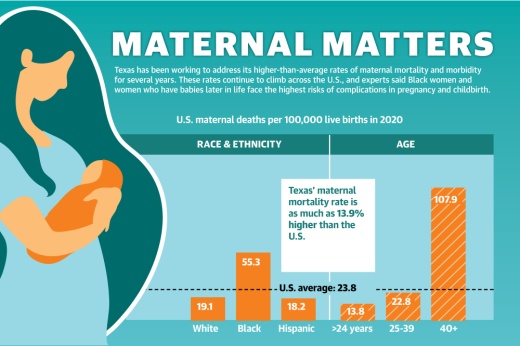

The average national maternal mortality rate was 23.8 per 100,000 births in 2020, an 18% year-over-year increase, which local health care providers said could partially be attributed to COVID-19. Black women in particular died at a much higher rate of 55.3 per 100,000 births that year, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Hall said the state’s maternal mortality rate may vary across different sources. However, Texas consistently ranks higher than the U.S. average in this metric across multiple studies.

The 2021 March of Dimes Report Card, which grades states on the health of mothers and infants nationwide, gave Texas a D grade and Harris County an F due to high rates of preterm births, infant deaths, inadequate prenatal care, social vulnerability factors and state policies.

Dr. Ericka Brown, interim local health authority at Harris County Public Health, said the state’s elevated maternal mortality rates also correlate to its high rate of uninsured residents and other barriers to care for underserved communities.

“The Texas Medical Center sits in Harris County, and it’s a little bit astounding that unfortunately we still have some of the highest rates of Black maternal and infant mortality,” Brown said.

HCPH is developing a culturally competent program to specifically improve outcomes for Black mothers, and the DSHS has implemented initiatives throughout the past decade to help address maternal mortality.

Identifying root causes

Researchers at ValuePenguin, an online data analysis tool designed to help consumers make financial decisions, gave Texas the lowest score of all 50 states in a study released in May about access to and the quality of prenatal and maternal care.

Health insurance research analyst Robin Townsend said while Texas ranked in the middle of the country when it came to the quality of infant and maternal care, Texas had the lowest percentage of women ages 18-44 with insurance coverage at 73.6% and the lowest percentage of women who had access to a primary care provider at 57%.

“So not only are they not able to access a primary doctor, but they really don’t have a lot of options for paying for that,” she said.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 20.4% of Harris County residents were uninsured in 2020 compared to 17.3% statewide and 8.7% nationwide. In comparison, 14.4% of Cy-Fair residents were uninsured.

“The way mortality is ranked for both mothers and infants, there are what we would consider provider causes, and then there are what’s considered nonprovider causes,” Brown said. “For Black moms, the provider causes, unfortunately, are higher than they are for our white mom counterparts, and I think that speaks a lot to the inequity in the social systems and the support around our Black moms and our Black babies.”

Cy-Fair ZIP code 77065 had among the highest rates of severe maternal morbidity between 2014-16, according to a study from The University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler. About 23% of the population of 77065 is Black, and 15.7% was uninsured in 2020, according to census data.

A single woman making less than $26,916 a year—a threshold more than 20% of one-person households in Cy-Fair falls below—could qualify for Medicaid to cover prenatal visits, labor and delivery, and checkups up to two months after giving birth.

The Texas Legislature passed House Bill 133 in 2021, extending that coverage to six months after birth, but experts said women with comorbidities often need to be treated before conception and more than six months after delivering their baby. Brown said Black women tend to have higher rates of risk factors, such as hypertension, obesity and diabetes.

Dr. Rakhi Dimino, an OB-GYN at Houston Methodist Willowbrook Hospital, said more than half of births in Texas are covered by Medicaid, but access is a challenge. Many women do not receive prenatal care until later in pregnancy due to the lengthy process of obtaining Medicaid coverage, she said. Texas has declined to expand its Medicaid program, which the Kaiser Family Foundation reported based on 2020 data would make 1.4 million additional nonelderly uninsured adults eligible for coverage.

Postponing pregnancy

Dimino said when she started her career 17 years ago, many of her patients were having children in their 20s, and now she is seeing more women wait until their 30s and even 40s to have children.

“For many of them, it’s getting to a point in their career that they’ve invested in in order to support having a family. They’ve delayed finding a partner; they’ve delayed childbearing specifically for their career,” she said. “And then once they are in that position, they are financially not having as many kids not just because of age, but the cost of raising a child is expensive.”

Harris County’s birth rate dropped 20% from 81.5 births per 1,000 women in 2007 to 65 in 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dimino said that trend has since been exacerbated as women have delayed pregnancy due to the pandemic.

The longer women wait to conceive, the more risks they can face in pregnancy and childbirth. The NCHS reported mothers age 40 and older faced a maternal mortality rate of 107.9 per 100,000 births in 2020. Women ages 25-39 died at a rate of 22.8 per 100,000 births.

“I think you have to respect the fact that there are higher risks as a woman gets older in terms of getting pregnant,” said Dr. June Marshall, who serves the Cy-Fair location of Tomball Woman’s Healthcare Center and is an OB-GYN on staff with HCA Houston Healthcare Tomball.

Reducing the rates

One way local hospital systems such as HCA Houston Healthcare help care for mothers is by offering prenatal education. Media Relations Director Annette Garber said staff has also undergone bias training to help ensure Black women receive the same level of care as their peers.

Marshall said education is key to equipping mothers to not only care for their babies, but to also care for themselves.

“Overall, for me it’s going to be education—making people aware that pregnancy is serious. The rewards are great, but the complications and the risk factors are as great, and one needs to be responsible,” Marshall said.

Statewide, nearly all hospitals that deliver babies participate in the TexasAIM to Reduce Maternal Mortality & Morbidity program, a DSHS initiative launched in 2018 to implement best practices in hospitals.

At the county level, Brown said HCPH is planning to establish a comprehensive program by the end of the year to target the county’s Black maternal mortality and morbidity rates. The initiative will help remove barriers to resources. While useful services may already exist, those who do not own a vehicle, for instance, may not be able to access them due to Harris County’s lack of a robust transit system.

“There’s a lack of education on many levels on what it looks like to remove barriers to care—whether it be wellness, clinical care, education, mental health, substance misuse,” Brown said. “To have a program is one thing, ... but to be purposeful in removing barriers so that those who need it most can take advantage of the program is another.”

Hannah Zedaker contributed to this report.