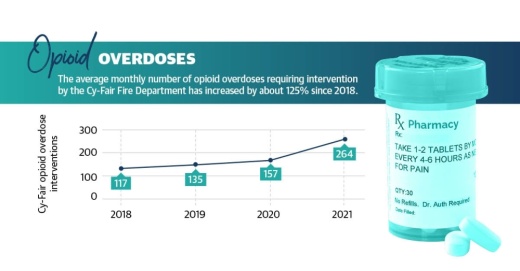

Justin Reed, assistant chief of emergency medical services for the Cy-Fair Fire Department, said the number of opioid overdoses requiring interventions in the department’s service area has risen by about 125% since 2018. Statewide, data from the National Center for Health Statistics has shown reported opioid overdose deaths nearly doubled in Texas from January 2019 to January 2021.

“These are diseases of despair that we’re dealing with,” said Tyler Varisco, a health services researcher with the University of Houston. “When people are economically challenged or psychologically challenged as many of us have been over the past two years, we see increased vulnerability in our communities to opioid use and other forms of substance misuse.”

With increased isolation and financial stresses, the COVID-19 pandemic further compounded struggles against the opioid epidemic in Texas, experts said. Recovery treatment transitioned into less effective online services, and access to quality treatment, such as medication, became more complicated.

Dr. Ericka Brown is the director of Harris County Public Health’s Community Health and Wellness Division, which oversees the countywide Opioid Overdose Prevention Program. She said treatment services locally were limited during the pandemic’s peak, but several federally funded programs aim to provide resources to mitigate drug use in high-risk areas locally.

“While we don’t specifically name that as a public health crisis, inequity across not just Harris County, but across the country, as we look at those who are underserved and the lack of resources for them is really a public health crisis. And unless and until we address that, we’re going to continue to see some of these epidemics flourish,” Brown said.

Opioid use over time

In the late 1990s, pharmaceutical companies began marketing prescription opioid pain relievers as drugs that were not as addictive as previously thought, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. As a result, these drugs, which had formerly only been prescribed to treat acute pain, became the prescription of choice to treat chronic, long-term pain.

Brown said countywide, white men are the most likely demographic to misuse opioids, although the epidemic also affects communities of color. While Reed said even high school students can access highly addictive drugs locally, the age group with the highest number of opioid overdoses in Cy-Fair is 36-50 followed by the over-50 age group.

“These are the folks who, through multiple surgeries and just regular health-related incidents, have been addicted to prescription opiates and are now switching to illicit supplies of it causing the overdoses,” he said.

In 2010, about 69 opioids were prescribed for every 100 residents of Harris County. A decade later, the number had fallen 45%, according to data from the Texas Department of State Health Services. However, a little more than one prescription was still issued on average for every three residents in Harris County in 2020.

While prescription misuse is still an issue to some extent, Brown said the county is seeing a rise in street drugs, such as lookalike prescription medications and fentanyl, a highly lethal opioid. The use of fentanyl in Harris County has risen by more than 100% since 2019, she said. Reed said the supply of heroin and other drugs coming in from outside the country is often laced with fentanyl, which has led to inadvertent overdoses locally. According to the NIDA, nearly 80% of heroin users reported using prescription opioids prior to heroin.

“Because of increased regulation on those prescription pills, [people who are addicted] either can’t get what they’re normally supplied, or they’re completely cut off, and so they’re switching to heroin to get their fix and then starting that down spiral into being addicted to heroin,” Reed said.

Pandemic effects on treatment

Varisco said the pandemic exacerbated several underlying causes of substance use, including patient access to treatment, increased financial stresses and isolation. He said he believes the changes to health care for individuals experiencing addiction undid recovery work performed for patients before the pandemic.

According to the Treatment Episode Data Set, which compiles national patient discharges from treatment for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, detoxification treatment discharges became less common from 2016-19, when detoxification discharges decreased from 20% of all discharges to 16%. “When you have a destabilizing event like a global pandemic, [vulnerabilities in health structures] become more evident,” Varisco said.

With in-person treatment at risk due to the coronavirus, health care centers went remote in 2020. Many centers were limited to offering substance use disorder care through telehealth services as opposed to in-person programs, complicating opioid recovery for patients.

Beth Welka, a licensed chemical dependency counselor at Positive Recovery Center in Jersey Village, said the outpatient substance use treatment program was forced to operate virtually at the start of the pandemic. She said she believes relapse rates were likely higher during that time.

“It’s difficult to treat substance abuse with that kind of barrier in the way,” Welka said. “It’s one thing when they’re here in group and they can get the support and we can really see how they’re being affected. ... You just don’t know how somebody is going to respond when they click off of Zoom and all of a sudden they’re at home alone.”

Government solutions

State and county entities are working to address the opioid epidemic through local funding, law enforcement resources and increased education surrounding opioid misuse.

Around 2018, Reed said a state initiative put Narcan—a device that dispenses naloxone overdose emergency treatment—on fire apparatus in addition to EMS units. The Cy-Fair Fire Department has intervened in more than 700 opioid overdoses since the start of 2018—more than 435 of which have happened since March 2020.

The department also works with Houston’s High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas to help identify overdose hot spots and mitigate the problem.

Similar efforts are ongoing at the county level. Brown said HCPH’s Overdose Data to Action program collects overdose data to inform local prevention and response efforts. HCPH also partners with the Harris County Sheriff’s Office to identify areas of high risk and provide resources to mitigate crime and drug use in those areas in the Violence Prevention Program.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton announced Feb. 16 the state had secured a $1.17 billion settlement with pharmaceutical companies AmerisourceBergen, McKesson and Cardinal. According to the Harris County Attorney’s Office, the county will receive $1.7 million annually over the next few years from this settlement.

The county is expected to receive $3.9 million in May from a settlement with Johnson & Johnson, and another $785,000 is expected this year from a settlement with Endo.

According to the attorney general, Texas has secured $1.89 billion to date from opioid settlements. These funds may be used for community drug disposal programs, training for first responders and youth-focused programs that discourage misuse.

Reed said he believes education can help prevent overdoses. Many people do not know, for instance, Narcan can be purchased at local pharmacies, and entities such as DanceSafe offer test strips online to ensure substances do not contain fentanyl.

“A majority of people have an addiction to something. They’re not any different,” Reed said. “They’re not a bad person. They just need to know that there’s people to come around them and lift them up and get them through this. And then for those that don’t even want to get clean at that moment in their life, there’s ways to be safe about your addiction.”